Firstly, it’s important to note that any kind of mask should always be worn in conjunction with following other measures such as regular hand washing, sanitisation and social distancing in order to be effective (WHO, 2020a). In this article I will tackle the issue of mask-wearing in a community setting from an overall perspective before delving into an examination and assessment of each type of mask available, so stay tuned!

Summary

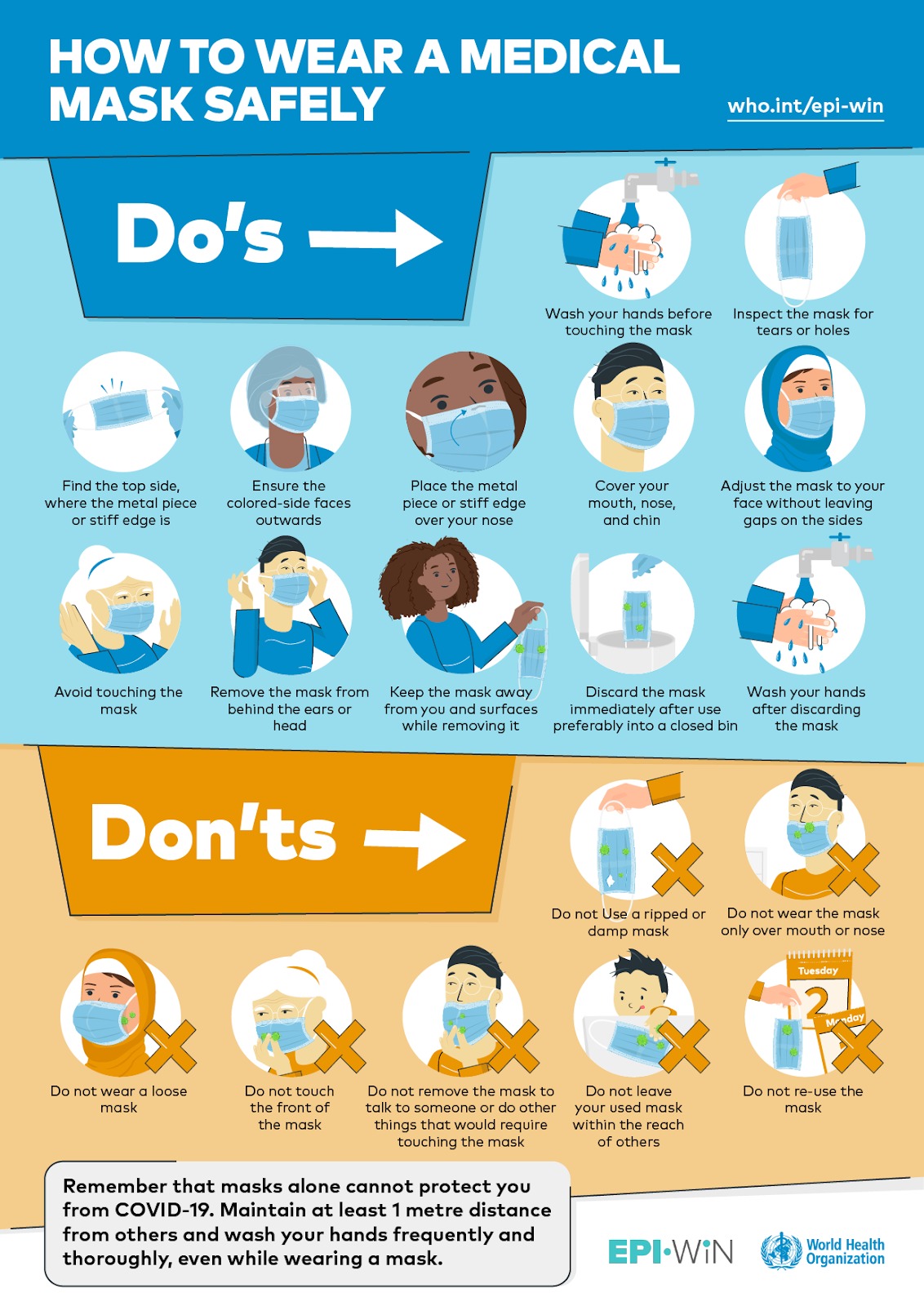

The use of face coverings overall, whether respirator, medical mask or homemade, have been proven to be effective for usage in a community setting, as they do reduce airborne droplet transmission (Anfinrud et al., 2020; Greenhalgh et al., 2020). However, the efficacy (i.e. how much it reduced droplet transmission by) differs between masks and between materials used to make homemade masks (Edelstein and Ramakrishnan, 2020). Therefore any kind of mask is better than none, but there are things you can do to make sure your mask is as effective as possible (See WHO do’s and don’ts poster), and always follow social distancing and hand-washing measures closely. For advice and help on making your own mask, see the section on fabric masks. Remember, current estimates suggest that 40% of COVID-19 cases are caused by those who are asymptomatic (i.e. don’t have any symptoms), so wearing a mask even if you feel healthy may help protect others from becoming infected (CDC, 2020a).

There are key differences both scientifically and physically between different types of masks, and some should be prioritised for use in a clinical setting (respirators). I am going to explore 3 different categories of face masks in this article: N95 respirators, medical face masks and homemade/fabric masks.

Respirators

Firstly, respirators are the masks commonly used in professional healthcare settings such as hospitals and care homes and look like this (see Figure 1). Current evidence has shown that respirators are effective at protecting the wearer from transmitting or contracting the virus (i.e. passing it on to others or becoming infected themselves (MacIntyrea and Chughtaib, 2020)), and they may be more effective than surgical masks – although there is some contention over this (Smith et al., 2016; Radonovich et al., 2019). Face coverings are most effective in reducing incidence of disease transmission when you are already sick, but emerging evidence also suggests that face coverings (in combination with hand-washing) can also be used to prevent the airborne transmission of airborne viruses in a community setting for people who are not yet ill (Jefferson et al., 2008; Aiello et al., 2012).

Organisations such as the CDC in the United States are recommending that respirators are reserved for those on the front-line in clinical settings (CDC, 2020c). However, in the UK the advice is less clear with some hospital settings still reporting shortages of PPE including face masks, gowns and ventilators, but others saying they now have sufficient stock (BMA, 2020a; BMA, 2020b). This means that until further advice is published – or shortages are reduced – the general public should not use respirator/N95 masks, as supplies should be reserved for medical workers both for current demand and in preparation for the second wave of Covid-19. The National Audit Office has produced a preliminary report on the failings of the government in its response to Covid-19 and the PPE shortage, if you would like to read further into why and how the shortages faced by the NHS came about (NAO, 2020).

Figure 1: An N95 Respirator

Figure 1: An N95 Respirator

Medical Masks

Medical masks are the mask you will probably be most familiar with. Common in medical settings, they are worn by dentists, surgeons and some doctors as a matter of course (See Figure 2). However, with the rise of Covid-19 medical masks have become more common, and increasingly difficult to get a hold of (WHO, 2020b). This means that the priority for medical masks should be given to those on the front-lines in the medical field or those that are medically vulnerable. However, as stocks are replenished medical masks can and should be used by the general public. Medical masks are generally accepted to be the second best form of protection from airborne viruses after respirators, although as mentioned earlier there is contention over this point (Smith et al., 2016; Radonovich et al., 2019). Nonetheless, all studies are clear that medical masks are more effective than most fabric masks, largely due to the standardised controls on their production and certification (Greenhalgh et al., 2020; MacIntyre et al., 2020). Therefore as long as you’re not hoarding them – causing front-line workers to be without – and are disposing of them responsibly, it is a good idea for the general public to purchase and use medical masks (Liang et al., 2020). You should however be aware of the impact of single use medical masks on the environment, and keep up to date with the constantly changing advice when it comes to effectively made fabric masks versus surgical masks. For more information on the effect of single use PPE on the environment, read the study on COVID plastic waste by UCL here (UCL, 2020).

If you do have a medical mask, it is important to reiterate they are single use. This means when you change settings or remove the mask (which must be done in a careful way as outlined in the WHO poster in this article), then it must be disposed of. Medical masks are NOT reusable or safe to use after washing like fabric masks can be, so ensure you have enough to cover your needs if you are going to be relying on medical masks.

Figure 2: A medical/surgical mask

Figure 2: A medical/surgical mask

Fabric Masks

A fabric mask in this context is talking about those masks you make at home, and come in a range of fabric, layers, fits and patterns. The efficacy of fabric masks varies greatly depending on their design and fabric, but studies suggest that even a poorly made fabric mask provides better protection/transmission reduction than nothing (Davies et al., 2013; Chu et al., 2020).

Organisations such as the World Health Organisation, NHS and CDC are recommending that the public use fabric/homemade masks (NHS, 2020; CDC, 2020b; WHO, 2020a). Recent UK legislation also means you are required to wear a face covering (including fabric masks) on public transport, in shops and when visiting hospitals or other medical facilities such as pharmacies (UK Government, 2020). Fabric masks are easy to make, cheap to buy and in plentiful supply and therefore means everyone can access a level of basic protection. However, it is clear that fabric masks should NOT be used in clinical settings, and if other masks/PPE are available such as medical masks or respirators then they should be used as an alternative (CDC, 2020b).

Figure 3: A homemade/fabric mask

Figure 3: A homemade/fabric mask

To this end, here is some guidance on how to make the most effective mask possible:

‘The ideal combination of material for non-medical masks should include three layers as follows: 1) an innermost layer of a hydrophilic material (e.g. cotton or cotton blends); 2), an outermost layer made of hydrophobic material (e.g., polypropylene, polyester, or their blends) which may limit external contamination from penetration through to the wearer’s nose and mouth; 3) a middle hydrophobic layer of synthetic non-woven material such as polyproplylene or a cotton layer which may enhance filtration or retain droplets.’ (WHO, 2020a).

There are also a lot of YouTube videos, government advice and tutorials from various medical associations. The most important things to remember whatever tutorial you decide to follow is that it’s the fit and the material that will determine how effective your mask is (WHO, 2020a; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2020). It should fit tightly (without causing excessive discomfort), so that no air escapes around the mask which would defeat the point of wearing it. Then the material choice should be as detailed above, with an inner cotton layer, middle synthetic lauer and an outer polyester or similar layer. If you have a respiratory condition that will stop you being able to use a mask, talk to your doctor and follow NHS guidance, perhaps considering a visor which may provide some protection.

So overall, yes masks work. If this incredibly detailed and well sourced article doesn’t persuade you that wearing a mask is a good idea, then I honestly don’t know what will. So this is your friendly reminder to not believe your favourite crystal healing YouTuber that masks reduce blood oxygen levels, don’t believe your conspiracy nut second cousin when they say that the government is using masks to develop face-tracking, and whatever you do please DO NOT go coughing or spitting in other people’s faces because you feel offended by the fact that they are wearing a face mask to protect themselves and others.

Stay safe and mask up!

Reference List

Aiello, A.E., Perez,V., Coulborn, R.M., Davis,B.M.,Uddin, M. and Monto, A.S. (2012). Facemasks, Hand Hygiene, and Influenza among Young Adults: A Randomized Intervention Trial . Plos One, [online]. Available at: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0029744 [Accessed 18 July 2020]

Anfinrud, P., Stadnytskyi, V., Bax, C.E. and Bax, A. (2020). Visualizing Speech-Generated Oral Fluid Droplets with Laser Light Scattering. The New England Journal of Medicine, 382, pp. 2061-2063.

British Medical Association, (2020a). Doctors still without adequate supplies of PPE, major BMA survey finds. [online] Available at: https://www.bma.org.uk/bma-media-centre/doctors-still-without-adequate-supplies-of-ppe-major-bma-survey-finds [Accessed 20 July 2020]

British Medical Association, (2020b). FAQ: Respirators and Ventilators. [online] Available at: https://www.supplychain.nhs.uk/covid19/faqs/ [Accessed 20 July 2020]

Centre for Disease Control, (2020a). COVID-19 Pandemic Planning Scenarios. [online] Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/planning-scenarios.html [Accessed 18 July 2020]

Centre for Disease Control, (2020b). About Cloth Face Coverings. [online] Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/about-face-coverings.html [Accessed 18 July 2020]

Centre for Disease Control, (2020c). N95 Respirators, Surgical Masks, and Face Masks. [online] Available from: https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/personal-protective-equipment-infection-control/n95-respirators-surgical-masks-and-face-masks#s1 [Accessed 20 July 2020]

Chu, D.K., Akl, E.A., Duda, S.,Solo, K., Yaacoub, S. and Schünemann, H.J. (2020). Physical distancing, face masks, and eye protection to prevent person-to-person transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet, 395 (10242), pp.1973-1987.

Davies, A., Thompson, K-A., Giri, K., Kafatos, G., Walker, J. and Bennett, A. (2013). Testing the Efficacy of Homemade Masks: Would They Protect in an Influenza Pandemic? Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness, 7(4), pp.413-418.

Edelstein, P. and Ramakrishnan, L., (2020). Report on Face Masks for the General Public - An Update. DELVE Addendum MAS-TD1, [online] Available from http://rs-delve.github.io/addenda/2020/07/07/masks-update.html [Accessed 18 July 2020]

Greenhalgh, T., Schmid, M.B., Czypionka, T., Bassler, D. and Gruer, L., (2020). Face masks for the public during the covid-19 crisis. British Medical Journal, [online] Available from https://www.bmj.com/content/369/bmj.m1435 [Accessed 18 July 2020]

Liang, M., Gao, L., Cheng, C., Zhou, Q., Uy, J.P., Heiner, K. and Sun, C. (2020). Efficacy of face mask in preventing respiratory virus transmission: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Travel Medicine and Infectious Diseases, [online ahead of print] 36. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32473312/ [Accessed 20 July 2020]

MacIntyre, C.R., Seale, H., Dung, T.C., Hien, N.T., Nga, P.T., Chughtai, A.A., Rahman, B., Dwyer, D.E. and Wang, Q. (2020). A cluster randomised trial of cloth masks compared with medical masks in healthcare workers. British Medical Journal Open, [online] 5(4). Available at: https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/5/4/e006577 [Accessed 20 July 2020]

MacIntyrea, C.R. and Chughtaib, A.A. (2020). A rapid systematic review of the efficacy of face masks and respirators against coronaviruses and other respiratory transmissible viruses for the community, healthcare workers and sick patients. International Journal of Nursing Studies, [online] 108. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7191274/ [Accessed 20 July 2020]

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2020). Rapid Expert Consultation on the Effectiveness of Fabric Masks for the COVID-19 Pandemic (April 8, 2020). Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, pp.1-7.

National Audit Office. (2020). Readying the NHS and adult social care in England for COVID-19. London: National Audit Office, pp.1-69.

NHS, (2020). Face Coverings In Our Hospitals from 15 June. [online] Available from: https://www.ouh.nhs.uk/news/article.aspx?id=1298 [Accessed 20 July 2020]

Radonovich Jr, L.J.,Simberkoff, M.S., Bessesen, M.T., Brown, A.C., Cummings, D.A.T., Gaydos, C.A., Los, J.G., Krosche, A.E., Gibert, C.L., Gorse, G.J., Nyquist, A-C., Reich, N.G., Rodriguez-Barradas, M.C., Price, C.S., Perl, T.M. and ResPECT investigators. (2019). N95 Respirators vs Medical Masks for Preventing Influenza Among Health Care Personnel: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Journal of the American Medical Association, 322(9), pp. 824-833.

Smith, J.D., MacDougall, C.C., Johnstone, J., Copes, R.A., Schwartz, B. and Garber, G.E. (2016). Effectiveness of N95 respirators versus surgical masks in protecting health care workers from acute respiratory infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 188(8), pp.567–574.

Tom Jefferson, T., Foxlee, R., Del Mar, C., Dooley, L. Ferroni, E., Hewak, B., Prabhala, A., Nair, S. and Rivetti, A. (2008). Physical interventions to interrupt or reduce the spread of respiratory viruses: systematic review. British Medical Journal, 336 (7635), pp.77-80.

UCL. (2020). The environmental dangers of employing single-use face masks as part of a COVID-19 exit strategy. [PDF] London: UCL Plastic Waste Innovation Hub. Available at: https://d2zly2hmrfvxc0.cloudfront.net/Covid19-Masks-Plastic-Waste-Policy-Briefing.final.pdf [Accessed 20 July 2020]

UK Government, (2020). Face coverings: when to wear one and how to make your own. [online] Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/face-coverings-when-to-wear-one-and-how-to-make-your-own/face-coverings-when-to-wear-one-and-how-to-make-your-own [Accessed 20 July 2020]

World Health Organisation, (2020a). Advice on the use of masks in the context of COVID-19. [online] Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/advice-on-the-use-of-masks-in-the-community-during-home-care-and-in-healthcare-settings-in-the-context-of-the-novel-coronavirus-(2019-ncov)-outbreak [Accessed 18 July 2020]

World Health Organisation, (2020b). Shortage of personal protective equipment endangering health workers worldwide. [online] Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/03-03-2020-shortage-of-personal-protective-equipment-endangering-health-workers-worldwide [Accessed 20 July 2020]

Never knew there was so much research into masks - this was really useful!