Which arts issue did I choose and why?

Eight years ago, I was at a choral workshop, and one of the leaders took a bunch of us aside and said, “I’d like to discuss something with you- equal temperament.’ He split us into two groups and made us sing intervals. Afterwards he would play it on the piano, and make us sing it again. He pointed out to us that the notes we sang seemed slightly out of tune to the piano. This confused me, as when we sang the notes, they did not seem out of tune to me. He merely pointed this out to us; afterwards, he recommended a book, and we left, to continue with our day. I did not think much of it for a while until a few years later, when my choir director told us that we were singing too ‘in tune’ to the piano. She told us that there is not just one way of tuning, and explained what equal temperament was, and how it had come about. It still surprises me that although tuning and temperament is an issue which affects all musicians, it is rarely discussed, and so I decided to write more about it here as it is an area of interest for me. I did not know a lot about this topic before starting the research, however I was aware that many people thought that equal temperament confined many musicians, especially singers, as it prevented experimentation with tuning, which I thought was really important to address.

Research into the history and context of equal temperament

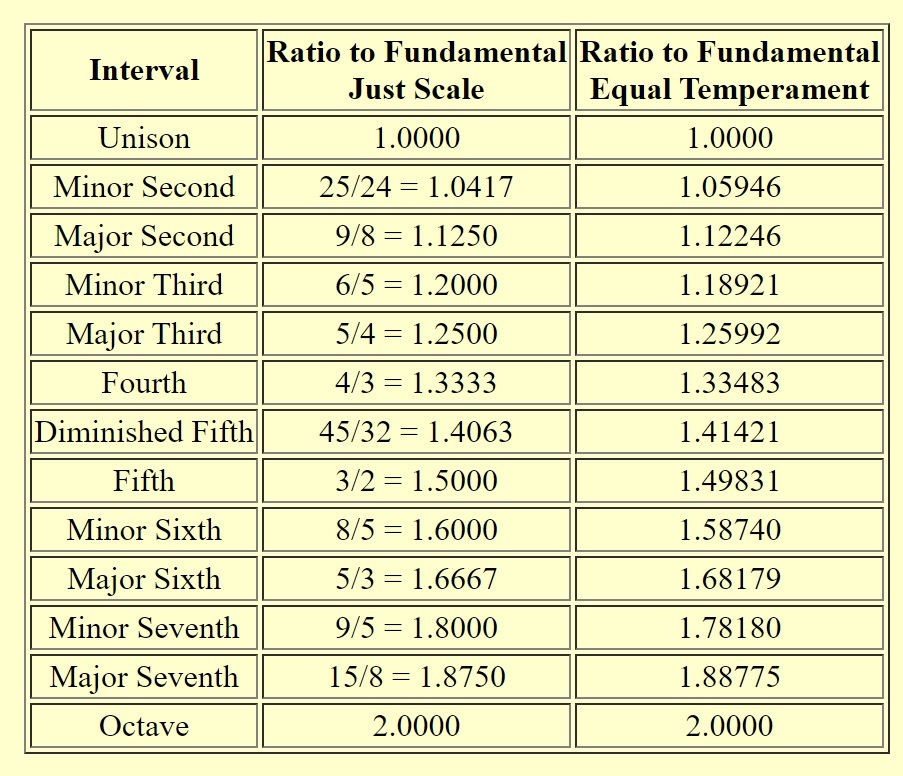

Equal temperament is a tuning system which compromises the tuning ratios of certain intervals in the scale. This allows for all scales to be played and sound good without re-tuning the instrument. For example, one can play all the scales on a piano, and they are all ‘in tune.’ There have been many tuning systems throughout history, which vary greatly throughout the world. Currently the most commonly used system, especially in the western world, is equal temperament, however this has not always been the case.

In the western world, one of the oldest fixed tuning systems is known as ‘Pythagorean tuning.’ Attributed to Pythagoras, it is based around the ratio 3:2, which produces a ‘pure’ perfect fifth. The aim was to create ‘just intonation:’ a tuning system where all the notes of the scale use whole number ratios of frequencies, and therefore are mathematically, physically, and audibly more pleasant. This idea was incredibly popular, however towards the renaissance period, with Tertian harmony becoming increasingly popular, many noted that the Pythagorean major third differed from what should be a ‘pure’ major third by what is known as a ‘syntonic comma’; this difference is extremely notable even to the untrained ear, and hence Pietro Aron set out a new solution to this problem by creating a new tuning system: ‘meantone temperament.’ This comprises the purity of the fifth to increase that of the third which was considered a necessary compromise by the musicians of the time.

Another issue with ‘just intonation’ is that when one does tune an instrument to these ratios, only one scale will sound in tune. This is acceptable when performing in one key, however does not work on many instruments which need to be able to play multiple keys and sound decent without having to retune it, such as keyboard instruments or the lute. And thus began the constant compromise of pure, just harmony.

Bach wrote a work known as ‘The Well-Tempered Clavier.’ By this he meant a tuning system which allowed the keyboard player to modulate between keys. This term later became used to describe a large range of temperaments and tuning systems which were created with this aim that used to be in use.

The solution which eventually became across the globe is one known as ‘twelve-tone equal temperament,’ ‘12-TET’ or ‘equal temperament for short. Although approximations were made for many years before it was adopted, one of the earliest being by He Chengtian, a mathematician in 400AD, till the 1600s the approximations of an equal temperament semitone were constantly varying, however only by a small amount.

Research into a range of views and reflection on them

The majority of people who love equal temperament tend to be pianists. It makes sense as without such a tuning system, they would not be able to play their instruments, as every time they changed key they would have to re-tune their instrument which is a laborious job. It allows for a lot of flexibility when modulating and allows for interesting chords which would not work in the same way with just intonation. Many would argue that it is the perfect compromise: it avoids the limitations of just intonation yet preserves the intervals better than many other temperaments. On top of this it allows for flexibility in composition. Many romantic and 20th century compositions would have sounded very unpleasant to the ear if just intonation or even meantone temperament were used. For example, one can look at many of Debussy’s compositions and note his use of experimental harmony and modulation, which would not have been possible on a keyboard instrument without such a solution.

Equal temperament has been the primary tuning system in the western world since the 18th century. It has become something so default it is rare to find people straying from it, with the majority of compositions and popular music rarely using pitches out of what one would find on the standard piano. The piano is such an important instrument nowadays, and hence the majority of ensembles will have one: whether it be as an accompanying instrument to a soloist, an orchestra, or even a rock band, keyboard instruments will often be at the centre of many musical performances. It is the fault of the piano that equal temperament is therefore used in instruments which do not necessarily need it in ensembles, such as violins and cellos. Many would argue this is a good thing: it prevents hassle over tuning systems and allows a range of instruments to play in a range of keys together.

Equal temperament has become accepted in our modern society for a reason. It resolves many issues with other tuning systems, however may say that we lost something because of it. It is a compromise of the truest, purest harmony which is rare to hear nowadays. At the time of Bach, instruments which could adjust the frequency of a note slightly such as violins or voices used different tuning systems to keyboard instruments. This is because they are able to adjust their tuning to different keys, and retain the purity of the harmony. Nowadays, however, equal temperament is adopted by the majority of instruments. This was likely a necessary change as 12-TET instruments such as the guitar or the piano became more common and more frequently used.

Today our ears are so accustomed to equal temperament, many who hear just intonation feel that certain notes are out of tune. Some think that this is worth lamenting, that we have lost a certain beauty of music, however if people do not notice the difference many would say that there is nothing worse about an adjusted frequency. People who would say that there is a beauty in pure harmony would point to studies such as ‘Howard DM. Equal or non-equal temperament in a capella SATB singing. Logoped Phoniatr Vocol. 2007;32(2):87-94. doi:10.1080/14015430600865607.’ This demonstrated that singers tend to sing in just intonation without the influence of equal temperament. I think that shows an inherent bias towards purer intervals, and many people would agree, however there have not been a significant number of psychological studies to determine whether this is true.

The final argument I have built up about the issue and evaluation of my research

It is rare for us to hear many pure intervals nowadays, as equal temperament has been adopted by almost all platforms of music. I would conclude that, although there certainly is a beauty around pure intervals, especially in a-capella choral music, equal temperament is a necessary sacrifice to allow for many instruments to play well in all keys. This however should not affect music on other instruments, not bound by equal temperament, with the capability to play in any tuning system with ease, such as the violin or the voice. These instruments, especially when not bound by a keyboard instrument, should experiment with their tuning. One should never be afraid to play slightly ‘out of tune’ in these cases: by sharpening and flattening certain notes slightly one can alter the entire atmosphere around the note. This flexibility and ability to experiment with different tuning is so important and should be encouraged more.

A very enlightening essay. The table you have added is a good illustration.