The arts have always reflected life to some extent, with many musicians, dramatists and artists taking inspiration from personal experience and evaluation of human nature. However, nowhere else in history can we see such a sudden and dramatic change in the arts than in their reaction to the First World War.

Nationalists

Music had been on a more emotional journey moving through the Romantic Period of around the 19th century up until this point, and it had succeeded in inflicting intense emotions upon an audience. This is where music for propaganda became fatally useful for the recruitment effort.

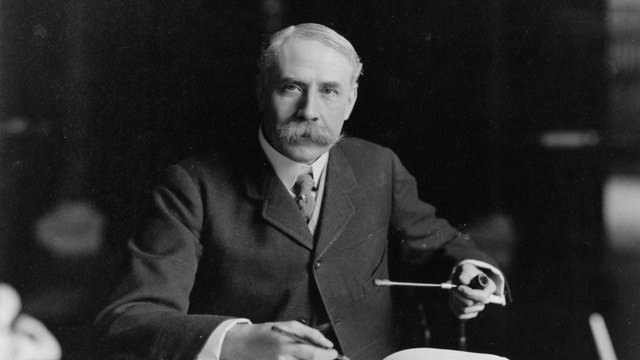

One of the most prominent composers who contributed to this Nationalistic movement was Edward Elgar, whose pieces we in Britain often still sing on special occasions. There is no use trying to deny that Elgar’s sweeping orchestral music fuelled the emotions and motivations of young men and patriots wanting to do their bit, as it still does with many people now.

Edgar Elgar

Edgar Elgar

However, we as modern listeners have the foresight to see that his music and lyrics presented an incredibly idealistic view of the world and what victory looked like, not to mention a product of his class and social circumstances. Young and impressionable members of the public, however, did not have this insight, and the music did a wonderful job of bringing people together to become heroes for their country.

This is also where popular war songs came about for younger, working-class listeners. They were designed to create a feeling of unity in upbeat ditties such as “It’s a long way to Tipperary” and “We’ll never let the old flag fall”, which sent young men giddily skipping off to war.

Music that got the blood pumping sent soldiers straight into the trenches of France, where they would experience just how much they had been lied to. The experience was so terrible that of the few men lucky enough to return, even fewer could talk about it. Though Elgar wrote pieces dedicated to fallen soldiers of war, the damage was done.

When propaganda proved false

No one was spared from the horrors, no matter who they were or where they were from, and this was presented in several literary works, one of the most well-known to this day being the 1929 novel by Erich Maria Remarque, ‘All Quiet on the Western Front’. The novel follows a young German soldier and his experience in the trenches, fighting alongside old school friends. It told of unimaginable physical and mental trauma in such a raw and touching way that the novel is still studied in schools today.

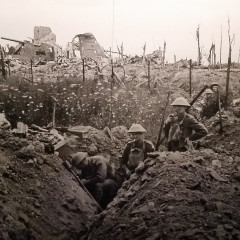

Soldiers in the trenches in France

Soldiers in the trenches in France

There was, and probably still is, no way to truly represent how horrible the trenches were. Nurses had been subject to the front line as well, devastated by what they had witnessed. However, advances in photography finally captured a real-life image as it was, and what people were able to capture of the hell where their brothers, sons, fathers, uncles and husbands had been sent shed a terrible light on what the war was really like.

With this new knowledge and understanding came a wave of social anger and criticism towards those elite few who had organised the fighting. It was so notoriously disastrous how little those who directed battles from behind desks knew of what was really happening, or cared to listen to advice from those who did.

Music’s reaction

Those who had experienced the war were changed forever, with experiences that no one would understand. There was, however, the possibility that music could reflect sounds and atmospheres that words couldn’t portray. Thus, music to sound pleasant and satisfying was challenged like never before.

Composers began to explore atonal music, music that couldn’t be categorised into a decisive key signature, or melodies that didn’t seem to fit the underlying chords. The result? A feeling of unease and apprehension that couldn’t be described in words. Time signatures and performance techniques were also challenged, creating music that one couldn’t tap along to with the changing beats and instruments played in an alien way from how people were used to seeing. An example of two such composers who challenged these mediums with dramatic effect was Gustav Holst with MARS from ‘The Planet Suite’ and Alban Berg’s ‘Three Orchestral Pieces’.

A very prominent composer who displayed new music-making methods was Arnold Schoenberg with the 12-tone method. ‘Instead of using 1 or 2 tones as main points of focus for an entire composition (as key centres in tonal music), Schoenberg suggested using all 12 tones “related only to one another.”’

It was almost as if everything that had constructed how music was written was turned on its head, creating a more individualised experience of music rather than a collective one. This meant that music became more of a talking point for interpretation instead of a generalised experience of mutual enjoyment (or at least was the idea).

Why did it all change like THIS?

Prior to the worldwide tragedy of the First World War, the primary social attitude around Europe was that humanity was constantly progressing, improving, and leading the world. Not coincidentally, the nations holding these values were dominated by corrupt aristocracies, with unimaginable divides between the working and upper classes.

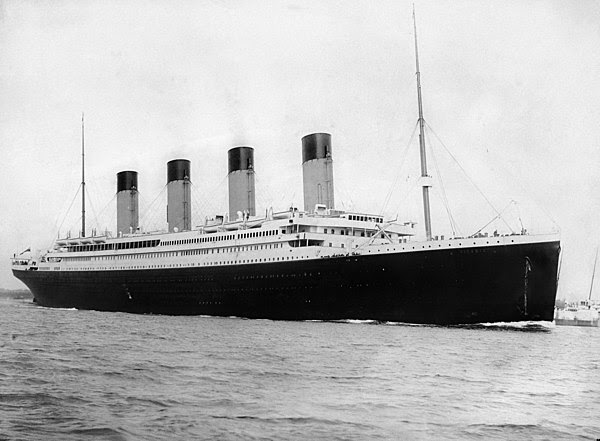

RMS Titanic 1912

RMS Titanic 1912

The early 20th century was not devoid of tragedy; the sinking of the Titanic had shocked the world only two years before the outbreak of war, but it was still a tragedy from which the rich primarily survived and moved forward with little to no consequence. The idealistic-thinking aristocracy had succeeded in pushing the progression narrative for centuries, but the First World War had turned this thinking completely upside down.

Living in the trenches was the ultimate equaliser that no one else had experienced unless they were there. Though middle and higher class men had been handed slightly senior ranking positions than the average soldier, this changed nothing when they arrived in the desolate, muddy, rat-infested pits they would live in for months on end.

The First World War happened on such a huge scale and was the first war of its kind in many ways, but probably the most important change was the ability to capture elements of it on film. It was clear that this idealistic vision of man’s constant progression to betterment was purely a fantasy the aristocracy delighted in pushing, and it would stop here. The upper class had played Icarus for too long, and there was only so far they could go without people noticing. Therefore, many composers chose to use their music to criticise society, with a driving focus on change and development over progression.

The Rest is History

The change in perspective that the First World War catalysed started a new journey in musical creation that has been evolving ever since. Many composers have followed suit, dedicating works to honour victims of tragedy and fatal human mistakes such as Benjamin Britten’s ‘War Requiem’ or Penderecki’s chilling ‘Threnody for the Victims of Hiroshima’.

Over in the USA, new styles known as ‘Jazz’ derived from music played by African slaves of the deep south were now the centre of decadent parties which raged upon the First World War’s end with the promise of new beginnings. This developed into the possibility of electronically enhanced volume and recording sound.

Music has constantly been evolving, but it seems that World War One set in motion the idea that music could take an audience to a whole new world of sound while, at the same time, telling the story of what was right in front of them.

0 Comments