In preceding centuries, the theatre had never shied away from criticising the state of current affairs and people in power, mainly in the form of satirical comedy and Shakespearean tragedy. The problem with this was that, though there was undoubtedly truth in its content, there seemed to be too much distance in the bridge between form and reality - especially in comparison to the consequential change in theatre as a result of the First World War.

A generation destroyed

The drastic social changes and the result of shameless and deceitful propaganda is something that I have outlined in part one of this instalment of Through the Ages. If you would like to look into why the creative arts changed so drastically in the way that they did, I highly recommend you read part one here.

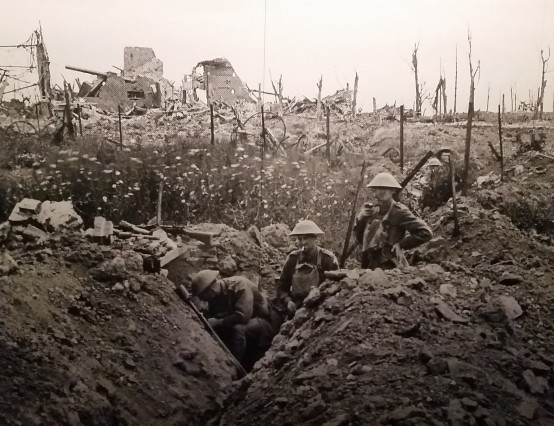

All in all, it was clear that the public and their soldiers had been let down catastrophically by their government and their shameless allowance of total slaughter in the face of pride, and it is safe to say that people were angry. It seemed that now, satire and tongue and cheek comedy wasn’t a fitting tribute to what could be represented in the theatre. The return of soldiers had revealed all too tragically the effects of the trenches. This fascinated the development of how theatre represented the human being.

‘Flanders Blues’

Characters at the front and centre of satirical comedy had primarily been the rich and ridiculous members of society. After the First World War, it became clear that there was a gap in representation for the every-man, and the consequences they faced as a result of the actions of the rich. The reason for this shift was very tragically, the inescapable results of the battlefield that had taken a toll on millions of soldiers’ mental health and neural system.

Shell Shock was one of the most prominent cases for returning soldiers, aptly named due to the shaking, twitching fits that possessed soldiers who had been subject to the endless explosions. However, this was not the only cause of the condition. Essentially, it was the sudden shock of being in a war with nowhere to escape and nothing to do but wait for battle. It was either constant noise, constant slaughter, loss of friends and family, constant murky conditions causing trench foot, or constant waiting for hours on end for the order to advance into No Man’s Land. Those who showed fear enough to refuse to fight or choose to flee were shot. For those who fought on, the often lifelong mental and physical effects were endless:

Shell shock

PTSD

Depression

Anxiety

Acute Paranoia

Insomnia/Parasomnia

Fits of hysteria

Hallucinations

Loss of Speech/Deafness

Paralysis

The misunderstanding of mental health and the expectation of men to be emotionally robust made the trauma all the worse. Therefore, gentler terms like ‘Flanders Blues’ became commonplace in the effort to explain why someone was, what hindsight tells us, was severe PTSD and depression.

Surrealism and theatre of cruelty

It seemed that the advancements of society, and in turn, the advancements of tactics and weapons, had done nothing but destroy, and the destruction lasted longer than anyone had anticipated. Amid the war, artists who wanted to criticise the flaws in society and the consequences of war and tragedy were already creating work intended to shock and force the viewer to look beyond what was right in front of them. The focus of the art, particularly in France, a country that was all but demolished during the war, was chaos and disorder instead of what used to be France’s prime art genre, romanticism. The extreme events of the war revealed much about the human mind and condition previously uncovered and ailments that had never been witnessed or recorded. Though there was much to be understood, and though it would take another century to come to terms with, mental illness and trauma had proved themselves devastatingly powerful, and artists took it upon themselves to portray it.

Back in France, Jean Cocteau had been making his name known for his Surrealist theatrical work. Some of his most influential pieces were Greek classics he had reinvented in the Surrealist style, marrying the ancient with the modern and shedding new light on some of the earliest written plays. Another Surrealist in France was Antonin Artaud (left), an actor and poet who later conceptualised the ‘Theatre of Cruelty. The ideas had been floating around during this time and just before the war. Ironically, the lack of logic and increasing surrealism made more sense after the war, resonating with people who had witnessed the tragic events of 1914-18. Conscripted into the French army for the First World War, Artaud was discharged for mental instability and opium addiction, which would persist for the rest of his life. Artaud wanted his theatre to be an immersive experience, using every sense to fully emerge his audience into the world of his creation. Essentially, he wanted there to be “no barriers between audience and performers”.

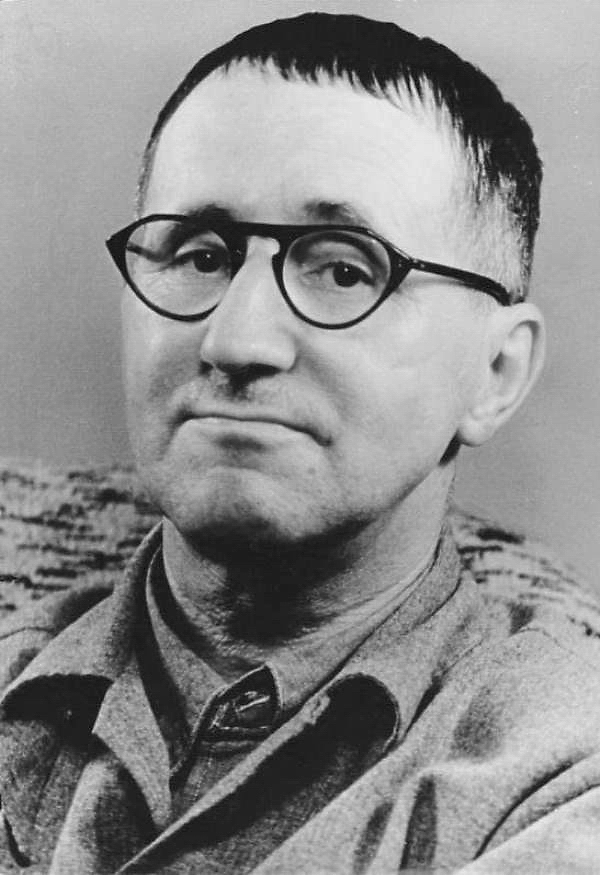

Brecht

One of the most influential theatre practitioners during this time was Bertolt Brecht, a German playwright whose mission was to inform, teach and influence. In almost the opposite way from Artaud or Cocteau, Brecht wanted to keep a constant separation from the audience and the action on stage. The aim was to strip emotional influence from the stage and force audiences to think with logic and reason, leaving the theatre in a more enlightened mindset and a better understanding of the social injustices that Brecht had highlighted. His work was devoid of romanticism, encouraging critical thinking. One of the ways he did this was to keep the audience constantly hyper-aware that they were viewing a theatrical performance - the stage was not meant to be a physical reflection of the real world, even though it was in the psychological sense.

Brecht remains one of the most influential practitioners to this day.

The close-up

The 1920s brought with it the development of film, later introducing ‘talking pictures’, the ability to record sound and visuals. Though this was a huge advancement in technology, the nature of the films was incredibly trivial. Actors such as Charlie Chaplin moving audiences to fits of laughter with his classic slapstick comedy, Wallace Reid wooing the screen in romantic scenes, and Douglas Fairbanks providing plenty of excitement in films such as The Three Musketeers and Robin Hood. These sold plenty of tickets, but the content of this art form had not made the contextual developments that the theatre had. That was ultimately because the screen provided a window into real life. Real people doing real things in real places. ‘The Big Parade’ of 1925 was one of a few silent films which depicted the front line of WWI and have since received praise for its non-glorification of war.

However, in the 30s, the industry began to challenge its ability to portray thoughts and feelings without mime or dialogue. Several films about life in the trenches were produced after the war ended, but, as one could expect, there was no way to truly portray the devastating conditions that front line soldiers experienced to cause such horrific trauma. Therefore, the people, characters, and psyche were at the front and centre of the screen, inviting audiences to understand just what was going on behind the facade. The development: the close-up shot.

The 1930 film adaptation of the novel ‘All Quiet on the Western Front' was a film that allowed the audience access and time to see the emotions of an actor’s face, inviting pure empathy rather than passive entertainment. This idea continued into the 40s and 50s beyond war films, indulging in the fascination of the psyche and how close-up shots could cater to actors’ abilities to emote without speaking. In 1954, the BBC broadcast a film adaptation of George Orwell’s ‘1984’. Unlike many films before it, especially in the BBC’s productions, the film consisted almost solely of mid-shots (from the hips upward), close-ups and extreme close-ups. The idea was to go through the journey of Winston Smith’s slow descent into a brainwashed dedication to Big Brother, a performance that Peter Cushing has been widely praised for.

Further developments in cinematography have led to limitless ways that directors can inflict emotions on an audience. From numerous cameras shooting one scene, tracking shots (a camera being drawn across on tracks), crane shots, hand-held cameras allowing for abstract angles - there are almost no limits to what film can achieve in the efforts to portray human emotion and psychology.

In short, the exposure to mental health issues after the first world war was so drastic and so sudden, and it seemed that artists, musicians and theatre practitioners were among the first to address it in a way that could be shared with the public in an effort to understand it. It was a new and terrifying world, and humanity had been changed forever. However, this unveiling of raw emotion and psychological impact has opened up a new understanding of what it means to be human. It was the creative minds (minds which were often previously looked upon as strange or unhinged), minds which lead with emotion and inventive ideas, that sought to empathise and sought to teach. And it seems, in many ways, that this mission has been ongoing ever since.

That’s a wrap

It has been a labour of love to create this series of articles, but incredibly rewarding. This series is by no means the source of all information. However, I hope that my intended purpose of giving background and unpacking some historical changes is interesting and encourages people to learn more about the classical arts, why they have developed, and how they have influenced and been influenced by Western society.

I hope this series has shown that the classical arts inform us about our history and society and that they don’t have to be reserved for certain groups of people. The arts are by the people, for the people.

0 Comments