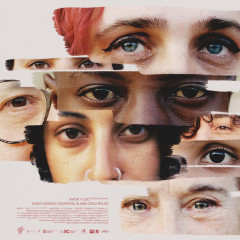

Last month I went to my local cinema, Genesis, to watch the Spanish documentary Alteritats/Otredades, or ‘Alterity/Otherness’ in English. The film was selected and screened as part of Last Frame Queer Festival, which took place over that weekend, from 13-16 July. The documentary was co-directed by Alba Cros Pellise and Nora Haddad Casadevall, and came out March this year in Spain. Last Frame Club went to a film festival in Malaga where they watched ‘Otherness’, and asked the directors whether they could screen it in the UK for their Festival, so I was fortunate enough to find myself watching the film’s UK debut!

I could really see why Last Frame Club were so excited about it by about two minutes in.

We are introduced to a community of lesbians living in Catalonia, I would say six “main characters”, although a lot of the filming and interviewing is done alongside their partners. These main characters identify as cis, trans, non-binary, or choose not to label themselves at all. Much of the questions put to them by Pellise and Casadevall are about their feelings about gender and gender expression, as well as sexuality. They are also all different ages, at different life stages and from different backgrounds. Even though they are all part of the lesbian community, Pellise and Casadevall indicate that the subjects of their documentary are not all the same with the same experiences, and they celebrate these differences. It was really ground-breaking to me to see this presentation of lives lived outside the heteronormative nuclear family norm, the struggles that they face because of this, and their choice to live authentically and fearlessly anyway. The film conveys that what makes them ‘other’ is what makes them happy – it doesn’t have to be a bad thing. Through interviews as the characters are just navigating their everyday life. Pellise and Casadevall both normalise their “lifestyles” and highlight the extraordinariness of them.

There were a couple of themes and moments in ‘Otherness’ that stood out to me. Firstly, the portrayal of the different experiences of family, when what this looks like deviates from the traditional nuclear family model. I thought the scenes where Manoly, a trans woman who has decided to raise their child without assigning them a gender, talks about her relationship with her mother to be particularly poignant. We hear that Manoly’s mother was so upset and confused by the fact that Manoly would not tell her the gender of her grandchild at first, but comes to accept this decision when Manoly comes out to her as trans. Over time, Manoly’s mother grows more understanding of her daughter’s transness. Manoly talks about how a real turning point in their relationship was when her mother re-gifted her an ugly gold bracelet. It used to have her deadname on it, but her mother changed it to ‘Manoly’. Something shifted in their relationship, and since then Manoly says that she wears it every day, even though it’s ugly. It was so beautiful to see how her mother’s shifting ideas about gender and her acceptance of Manoly made her so happy, and them so much closer. There had always been a distance between them before because Manoly felt she had to be masculine-presenting around her mother, and could not come out to her as trans or lesbian. To me, this shows that you don’t need to be what you think loved ones want you to be to be accepted by them, and that love adapts and grows. So it’s not just queer characters that Pelisse and Casadevall avoid putting into a box, it is Manoly’s mother too.

In contrast, another character, Fatou, shares that they have always felt judged by their community in Senegal, whatever they did, and that their mental health has suffered because of this. Unlike Manoly, their family does not know that they are queer. They talk about posting pictures with their girlfriend on Instagram, but not on Facebook. In Senegal, queerness is viewed as a Western influence. Fatou talks about having a duality of identity, living in Cataluna as a black Muslim lesbian; that they are rejected by society here as well as in Senegal. Their story is not a sad one either, though. We see Fatou host a dinner party with a group of friends who are also queer people of colour, and it feels like a depiction of a family – a chosen one within which Fatou doesn’t need to choose a box to fit in.

As well as alternate family structures, we see alternate relationship ‘structures’, if you can call them that. One perspective I thought was interesting was that of a character who moved out of the city to live and work on a farm. They feel that for a relationship to work there needs to be three people in it, to allow each person space if they need it – a take on boundaries and breaking out of the conventional structure of monogamy that I’ve never heard before. They said too that they do not identify as cis, but they would not change how their body looks. That if they were still living in the city, they might have been influenced to transition. Another character explores this same question of nature vs. nurture: is it the environment that impacts my identity, or is my identity something integral to me? They phrased it in terms of: how far are we ourselves for other people, instead of for ourselves? This person contrasts with the character who lives in the countryside on a farm, in that they are on and off hormones, changing how their body looks and how they present a lot. Both characters challenge any idea of a fixed, forever identity in different ways.

The last aspect I’d like to mention is the film’s portrayal of Kali, who towards the end of the film speaks about their experiences of rejection from other lesbians in the community because of their job as a sex worker. It was significant to me that the film spent time building up a sense of Kali’s life outside of work, before her job was mentioned. There are scenes of them skating with a friend, reading, and shopping. Their interior life too. They talk about their favourite books, and the time ten years ago when their dad asked them if they were about to go on a date with a woman, and they panicked and said no. It felt like this was to displace all of the stereotypes and stigma around sex work, this emphasis on the fact that they are not their job. Kali says that they can’t understand why other lesbians would discriminate, when they understand what it is to be discriminated against.

To wrap up, that was the first time I have ever watched a documentary that’s about lesbians, I think (astoundingly, the first suggestion of a film that comes up for me on Netflix is usually “Lesbian”…). If you too get personally targeted by lesbian media, go and watch… something similar to ‘Otherness’! Unfortunately, the film is currently doing its festival run in Spain, so it might be some time before it becomes available to watch in the UK. In the meantime, I’ve made a list of some LGBTQI+ documentaries and where you can watch them:

· Before Stonewall: The Making of Gay and a Lesbian Community (1984), YouTube

· Where Have All the Lesbians Gone? (2022), Channel 4

· Disclosure (2020), Netflix

· A Secret Love (2020), Netflix

· The Death and Life of Marsha P. Johnson (2017), Netflix

· Pride (2014) - not a documentary but I love it, Netflix

0 Comments