Wales has a law-making history that is thought to have begun in the 10th century. Hywel Dda, a king who ruled most of Wales, oversaw much of the structuring and restructuring of Welsh law at this time.

However, Wales was then partially conquered around 1094 during the Norman invasion of Wales, but Welsh forces fought back and regained control of most of the country around 1101. There continued to be friction between England and Wales, with a standoff between each country’s forces in place from 1135 to 1154 during the reign of Stephen, King of the English.

In 1157, King Henry II of England sought to change this, launching an attack on Wales that ended in a crushing defeat. However, tensions and attempts at conquering Wales continued and Wales eventually fully came under English rule between 1277 and 1283, due to Edward I’s ‘conquest of Wales’.

Discontent and dissent bubbled under the surface, and in 1400 came to a head when Owain Glyndŵr, the last true Prince of Wales, led a 15-year rebellion against English rule. In 1402 the English parliament issued the Penal Laws against Wales in an attempt to re-establish English dominance in Wales and squash the rebellion. These laws banned Welsh people from bearing arms, occupying positions in senior public office, and buying property in English towns. It also forbade public assembly, and sought to limit the education of Welsh children.

However, these laws failed to quell the rebellion, and instead provoked even more Welsh people into joining Glyndŵr. The rebellion saw the recapture of several castles and territories in Wales, with the Welsh forces ultimately regaining control of much of the country. News of Glyndŵr’s success spread and Scotland, Brittany and France sent military and naval aid to assist the Welsh forces.

Unfortunately, the significant gap in wealth and resources between Wales and England eventually took its toll, and by 1409 much of Wales had been recaptured by the English. Glyndŵr fought on, coming under siege at Harlech Castle but escaping by night, disguised as an old man. Glyndŵr and a band of loyal followers refused to surrender, retreating to the wilderness and continuing guerrilla attacks against English forces. Glyndŵr consistently refused to accept pardons from King Henry V of England and, despite the large ransom on his head, was never betrayed. Glyndŵr’s death aged 56 was recorded in 1415 by a former follower. Portrait of Owain Glyndŵr

Portrait of Owain Glyndŵr

English treatment of Wales and the Welsh people had softened after Henry V took the throne in 1413, with royal pardons being offered to many of the leaders of the revolt. Due to this the rebellion did not see a resurgence after Glyndŵr’s death.

The cultural conquest of Wales

During the reign of Henry VIII, in 1535 and 1542 the Laws in Wales acts were passed which officially annexed Wales to the Kingdom of England, making English laws enforced in Wales also and specifying English as the language of the law. However, it did establish separate judicial structures in the Court of Great Sessions for Wales. But in 1746, the Wales and Berwick Act made it so that by legal definition Wales and Berwick were now officially ‘England’, and in 1830 the Court of Great Sessions was scrapped, removing Wales’s last recognizable independent legal powers.

During this time Wales was still facing attacks upon its own culture. The Welsh language was seen as a kind of ‘sickness’ and a three-part publication by the British government in 1847 that came to be known as the Blue Books condemned not only the Welsh language, but also Welsh people, stating that the Welsh were unruly, stupid, and promiscuous, and that the language was feeding into this.

Partly as a result of this, schools across Wales used ‘the Welsh Not’, a plank of wood with ‘W.N’ carved into it that was hung around the neck of a child with rope if they were caught speaking Welsh – the first language of the majority of the population at that time. The child could get out of bearing the Welsh Not if they told on another child for speaking Welsh, at which point the Not would be passed to them. The child who was left wearing the Welsh Not at the end of the school day would be beaten by the teacher. The use of the Welsh Not was widespread during the 1800s, but it’s use has been reported from as early as the 1700s and as late as the early 1900s.

The Welsh Not by Amgueddfa Cymru

The Welsh Not by Amgueddfa Cymru

In 1886 Welsh Londoners including future prime minister David Lloyd George established the group Cymru Fydd to advocate for a self-governed Wales. The group spread to other English cities with large Welsh populations and also to Wales but dissolved without any real achievements. The first true steps towards devolution arguably began in 1907 when the Welsh Board for Education was established, and furthered in 1920 with the disestablishment of the Anglican church in Wales.

The catalysts for devolution

It wasn’t until the 1940s and 1950s that devolution finally became a focal talking point. Petitions for a Secretary of State for Wales were turned down by the Labour government of 1945-1950, but, as a partial substitute, a Council for Wales and Monmouthshire was created in 1948.

In 1951 the newly elected Conservative government created the new position of a junior Home Office Minister of Welsh Affairs, which was upgraded to Minister of State in 1954 and was held by Gwilym Lloyd George. In the early 1950s the Parliament for Wales campaign brought a petition with 250,000 signatures calling for Wales to have a separate government with devolved powers. This was unsuccessful.

The 1960s saw more positive changes, with Labour creating the office of Secretary of State for Wales in 1964. It was initially a fairly limited position and included official responsibility for Wales and Welsh matters including allocating funding for certain public services. In 1967 Labour created the Welsh Language Act which repealed part of the Wales and Berwick Act, removing Wales from the legal definition of England, and widening the areas in which Welsh was permitted to be used, including in some legal settings.

Despite this the 1960s also saw several injustices against Wales and the Welsh people, including the flooding of Tryweryn and the Aberfan disaster.

The flooding of Tryweryn, often referred to now with the phrase ‘Cofiwch Dryweryn’ (Remember Tryweryn), occurred in 1965 after Liverpool City Council obtained permission to flood the entirety of the Tryweryn Valley in Wales to provide water for Liverpool, without the permission of any of the local Welsh authorities or the consent of Welsh members of parliament. The residents of the valley were forced to move, losing their homes to make way for the reservoir, many of them from the centuries-old village of Capel Celyn – one of the last Welsh-only speaking communities in the country.

The remains of Capel Celyn exposed by low water levels at Llyn Celyn reservoir by Oosoom

The remains of Capel Celyn exposed by low water levels at Llyn Celyn reservoir by Oosoom

The move was incredibly controversial, with protests happening in Liverpool, London, and Wales, and musician and journalist Meic Stephens painting the slogan ‘Cofiwch Dryweryn’ (originally misspelt as ‘Cofiwch Tryweryn’) on to the wall of a ruined cottage in mid Wales – the origin of the phrase that has now become a political slogan for Welsh nationalism and independence.

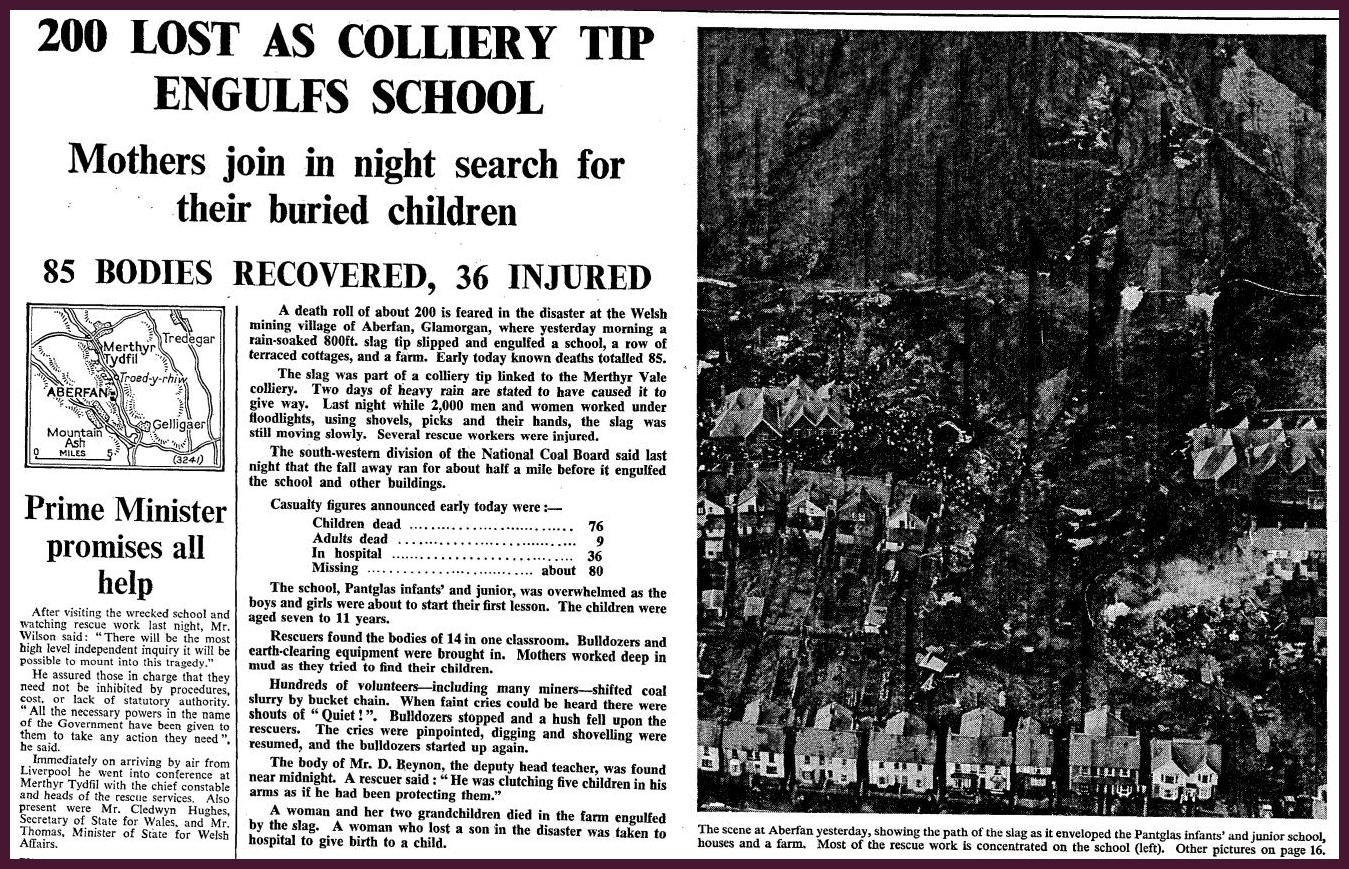

The Aberfan disaster occurred in 1966, when a colliery spoil tip collapsed above the mining town of Aberfan, engulfing the primary school and a row of houses and killing 116 children and 28 adults. The colliery tip was the responsibility of the National Coal Board (NCB) which was found to be to blame for the tragedy by a subsequent inquiry. Due to poor decisions and negligence the NCB had allowed the tip to be created above a natural spring. When three weeks of heavy rainfall occurred in 1966, the tip became saturated and collapsed. The NCB was never prosecuted or fined for its responsibility, and residents of Aberfan were forced to engage in a lengthy fight with NCB just to have the remaining tips above the town removed.

A newspaper clipping about the Aberfan disaster by Bradord Timeline

A newspaper clipping about the Aberfan disaster by Bradord Timeline

These injustices provoked action from Welsh nationalist terrorist groups. Mudiad Amddiffyn Cymru (MAC) was a paramilitary Welsh nationalist organisation created in response to the proposed flooding of Tryweryn in around 1963. They undertook a series of bombing incidents between 1963 and 1969, primarily targeting infrastructure that carried water to Liverpool. The groups intentions were never to cause casualties and bombs were timed and placed only to affect buildings and infrastructure. However, due to a bomb malfunctioning a 10-year-old boy was injured in 1969, and two MAC members were killed due to a bomb malfunctioning several days earlier.

The Free Wales Army was another paramilitary Welsh nationalist group also formed in 1963. The Army often encouraged media attention and claimed responsibility for several of MAC’s bombings, but were never taken very seriously by the media. However, they played an important role in supporting the rights of Welsh people, including advocating for the families of victims of the Aberfan disaster who were being denied compensation.

Neither of the groups are officially still active today, with much of their action ceasing after members of both groups were arrested in 1969. Nine members of the Free Wales Army were arrested and six of them were convicted, including leader Julian Cayo-Evans. John Jenkins, leader of MAC, was arrested in November of the same year and convicted of several offences in April 1970. Although there were a handful of bombings after 1969, there is no evidence that MAC were responsible.

Devolution becomes a focal talking point

The 1970s saw further calls for devolution. In 1973 the Royal Commission on the Constitution recommended that both Wales and Scotland have their own elected bodies. Despite criticisms from within its own party, the Labour government of 1977-1979 expressed plans to hold a referendum. They did so on St David’s Day in 1979, proposing the establishment of an elected body for Wales. However, by a majority of 4 to 1, plans for devolution were defeated.

At this time there was also a housing crisis in Wales that exists to this day, caused by wealthy English people buying holiday homes in Wales. This drives up house prices, and therefore makes it impossible for Welsh people to afford most of the houses in their own area.

One of the more extreme recent results of this is the village of Cwm-yr-Eglwys in Pembrokeshire, which now has only two out of fifty properties that have permanent residents. It’s last remaining residents no longer have a village shop or pub as businesses can’t afford to open there outside of the holiday season. Most Welsh people can’t afford to move back into the area either, with houses there costing well above the national average, and one home being priced at £1.3 million.

Due to this, 1979 also saw the creation of another Welsh terrorist group, Meibion Glyndŵr, which translates to ‘Sons of Glyndŵr’. Meibion Glyndŵr formed in direct response to the housing crisis and their aim whilst they were still in operation was to burn white English people’s holiday homes as a form of protest. The first round of incidents saw 8 homes being burnt within the space of a month, and they destroyed 220 properties over the next 10 years.

Remains of a burnt holiday home by Eric Jones

Remains of a burnt holiday home by Eric Jones

In the late 1980s they specifically targeted the second homes of Conservative MPs, including the Welsh secretary at the time David Hunt. They also planted fire bombs in Conservative party offices in London and in a number of estate agents’ offices in England and Wales. Sion Aubrey Roberts was arrested in 1993 in connection with the bombings, resulting in the only known conviction of a Meibion Glyndŵr member.

Devolution

In the same year, the Welsh Language Act put Welsh on equal footing with English in many aspects of public life by finally repealing the Laws in Wales Acts – which dated back all the way to the 16th century. Despite the overwhelming defeat of the 1979 referendum, support for Welsh devolution had continued to grow, and in 1997 Labour made manifesto commitments to hold referendums for Welsh and Scottish devolution.

Just four months after taking office, Tony Blair’s government held a referendum on 18 September 1997, with 50.3% voting in favour of devolution for Wales. In 1998 the Government of Wales Act was passed in the UK parliament, and on 12 May 1999 the National Assembly for Wales met for the first time.

However, it wouldn’t be until the Wales Act of 2017 that the Assembly would become a permanent part of the constitution. This could be considered as somewhat indicative of a persisting level of fragility and uncertainty in the way Westminster treats devolved Wales. Although devolution has been a key step forward in representing and protecting the rights of Welsh people, some believe that further powers or independence are needed for a truly prosperous and thriving Wales.

0 Comments