Like everyone else, I’ve spent more time indoors this year than expected. Mercifully, the quality and breadth of new writing in bookshops – or rather online stores – this year has afforded me a well-enough stocked shelf to keep my sanity. Whether you’re looking to travel to imagined worlds or for outstanding debuts that hit closer to home, the following titles make for excellent company.

I’ve mixed fiction, non-fiction, and poetry, so let’s take things from the top in alphabetical order. Here are Voice’s ten must-read books from the last twelve months.

Surge, Jay Bernard

(Chatto & Windus)

An exploration of the New Cross Fire in 1981, Jay Bernard’s Surge takes up the mantle of the Black People’s Day of Action, a movement which sought justice for the 13 young Black people killed in the south London blaze. Based on interviews and inflected by the Grenfell Fire of 2017, the Windrush scandal, and the wake of the Brexit vote, this poetry collection breaks through the indifference of a national press and government unwilling to look history in the face. ‘I am from here, I am specific to this place,’ writes Bernard, ‘I am haunted by this history but I also haunt it back.’ Two standout poems, ‘+’ and ‘–’, of a father who cannot hear the cries of dead son who is afraid of the dark, will floor you. They are heart-breaking. Even flashes of joy, of dancehall rhythms and the Jamaican patois of ‘Songbook’, give way to flames. There is urgency here. There is documentary, there is deftness of lyric. Bernard is an outstanding writer who weaves each strand with due care and attention. Surge is a worthy winner of the Sunday Times Young Writer of the Year Award.

_

One Two Three Four: The Beatles in Time, Craig Brown

(4th Estate)

From poetry to non-fiction now, Craig Brown’s book on the Fab Four is eclectically and interestingly brilliant. Winner of this year’s Baillie Gifford Prize, One Two Three Four delves in the band’s history, into diary entries, fan letters, party lists, charts, interviews, the works. Anecdotes merge with biography, and biography with discography. It’s great fun, and Brown gives new shine to old legends. One moment we’re reading about the Beatles’ nonsense lyrics in ‘Come Together’, then of Alice in Wonderland, then of Spike Milligan and The Goon Show. The book makes room for the tangential and delights in the stories that have collected around the group over time. Men after my own heart, the Beatles loved a good pun (you can tell from their band name). It’s a preoccupation Brown makes the most of, leading to some of my favourite passages in the book. ‘You can sack Rome,’ says Lennon, ‘or you can sack cloth – or you can sacrilege, or saxophone, if you like, or saccharine.’ Or maybe sacrosanct, if you prefer. There’s a bit of all of them in there.

_

The Swallowed Man, Edward Carey

(Gallic Books)

‘My son, my love, my art’. The Swallowed Man is Edward Carey’s twist on a classic tale. The novel tells the story of Geppetto, Pinocchio’s father, and the two years he spent shipwrecked in the belly of an enormous sea creature. It takes the form of a journal, written by Geppetto during his time of isolation. Carey’s prose is poetic, enjoyably antiquated and Melvillian, but with a wicked streak that saves it from mawkishness. There’s plenty of mischief here and it’s a delight to read. The puppet-maker’s illustrations are Carey’s own in his characteristic style (I’d recommend you check out his Twitter for more of his artwork). Not only do the diagrams, scrawls, and art objects make for a beautiful book, they also illuminate the strange relationship between art-making, authorship, and parenthood. A brilliant reinvention of an uncanny fairy tale.

_

RENDANG, Will Harris

(Granta)

Winner of the Forward Prize for best debut collection, Will Harris’s RENDANG explores the poet’s Chinese-Indonesian and British heritage in a series of lyrics that play with form, prose-poetry, ekphrasis, moving between real and imagined locations, from London to Jakarta, to childhood videogames and ‘Planet Mongo’. Meditations on the multiplicity of identity give way to flick-knife sharp observational humour. His poem ‘My Name is Dai’ glints with the light of what feels like a real-life exchange, resulting in the soon-to-be immortal lines: ‘There are people who relieve themselves / of information like a dog pissing against a streetlamp to mark out / territory’. But the poem turns in on itself knowingly. Dai is rude and a drunkard. He is also Welsh and resents that he grew up alongside the successful actor Michael Sheen. Like Coleridge’s Ancient Mariner, Dai goes on a bit and Harris skewers him for it. There’s a sense of forgiveness at the end of the poem. The collection is generally wary about casting people as a ‘type’. But Harrisknows better than to let him - or a good story - off the hook entirely.

_

Diary of a Young Naturalist, Dara McAnulty

(Little Toller)

Dara McAnulty is a teenager. He is autistic and a passionate naturalist. He’s also the winner of the 2020 Wainwright Prize for nature writing in the UK. This is perhaps no coincidence. Written of the year between his 14th and 15th birthdays, McAnulty’s lyrical memoir takes us from spring to spring, from Northern Ireland to County Down, with an exacting attention, sensitivity and empathy for the natural world. ‘It records the uprooting of a home,’ writes McAnulty, ‘a change of county and landscape, and at times the de-rooting of my senses and my mind.’ Diary of a Young Naturalist is a remarkable debut; a book that’s green in the best of ways.

_

Mordew, Alex Pheby

(Galley Beggar Press)

Indisputably the fantasy novel of the year, Alex Pheby’s wildly inventive book is set to be the first in a trilogy that unfolds in the ever-writhing, Gormenghast-like universe of Mordew. Nathan Treeves begins his hero’s journey with a secret talent, a kind of magic: he has the Spark. Wielding this creative force, Nathan can animate the world around him and give form to ‘the Living Mud’ on which his home, a sprawling Dickensian slum, is built. His father is dying of lungworm. There are firebirds. Someone called the Master is feeding off the corpse of God. The scope is immense, and my words run away with me as I try to pigeonhole the extraordinarily expansive and curious world of Mordew. An exquisitely dark adventure that squirms with possibility.

_

Entangled Life, Merlin Sheldrake

(Vintage)

You may have heard of Cosmo Sheldrake, Merlin’s brother. He’s a musician that often mixes field recordings of the natural world with vocals and traditional instrumentation. What Cosmo achieves through song Merlin achieves in prose. So much more than a non-fiction book about the humble fungus, Entangled Life unveils a similar philosophy of interconnectivity informed by the study of mycology. The behaviour of fungi – if behaviour is the right word (the author uses metaphors freely, so I will too) – is a constant source of surprise and wonder. When Darwin wrote of the ‘entangled bank’ in his Origin of Species, of that patch of ground on which all life forms commune, he anticipated the intricate relationship of the ‘Wood Wide Web’ – a very modern metaphor for the mycorrhizal fungi that attach themselves to roots and form a network of information. Through this network, plants are said to ‘talk’ to one another. It’s truly an astonishing insight; a window into the super-organisms that literally keep the earth together.

_

Citadel, Martha Sprackland

(Pavilion Poetry)

Sprackland’s Citadel is extraordinary. A chameleonic debut collection, the ‘I’ of the poems is at once Juana of Castile, the sixteenth-century Queen of Spain, and the twenty-first century poet. The two are connected across moments in time, but let’s focus on the latter. In ‘Tooth’, a pain in the jaw hints at a trauma with a deeper kind of root. Food takes on new meaning: eggs and milk are sometimes of women’s bodies, sometimes breakfast. Individual lines, exceptionally put, echo themselves in unspoken ways. (In ‘Sickness like a fingernail moon’ I almost hear the word ‘sickle’, a foreboding crescent of another kind.) Various cycles – of the tide, of preening or ablution, of ovulation – converse throughout the collection. Body parts are often ‘disunited’, like the pickled hand in the Hunterian Museum or the dentist ready to do his job. I am deeply moved by this book, its tenderness and its violence. ‘The walls of the mind are deep and moated’, writes Sprackland. There’s plenty more to discover for those willing to scale them.

_

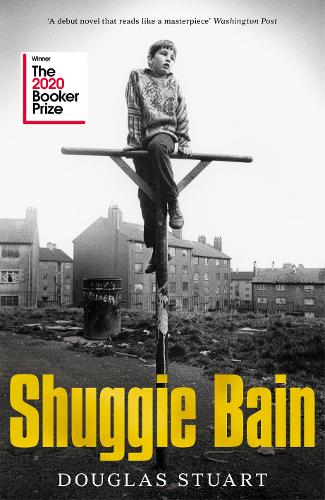

Shuggie Bain, Douglas Stuart

(Picador)

Another debut book, but this one has the 2020 Booker Prize under its belt. Shuggie is Agnes’s youngest. The rest of her children will abandon their mother to alcoholism, and he is the last to leave. Douglas Stuart’s uncompromising portrait of 1980s Glasgow, of poverty, abuse and a society left behind in the wake of Thatcherism, is shot through with violence, addiction and a vulnerable and complicated love. It’s a grim, heart-rending book – an unforgettable read that will stay with you long after you put it down.

_

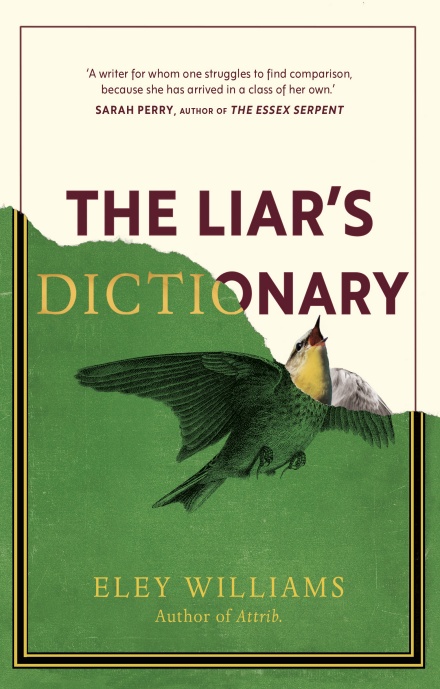

The Liar’s Dictionary, Eley Williams

(William Heinemann)

Eley Williams’s first full-length novel is warm, generous and exceedingly charming. Mallory, an intern at a behind-the-times dictionary publisher in London, unearths a trail of mountweazels – deliberate, misleading errors in the form of fake dictionary entries. What follows is a cat-and-mouse drama of love, labels and the secret language we use to define ourselves but seldom give voice to. To coin a line from the book, The Liar’s Dictionary gives real feeling to the ‘transformative power of proper attention paid to small things’. And the overall effect is exactly that: characterful, playful, deceptively transformative.

_

Now read the rest!

We're releasing Top 10 articles every day in the lead up to New Year! Click through on the banner below to find out what makes our list of the must consume culture!

Think we've missed something? Let us know in the comments below

0 Comments