An article written in 2018 by Julian Astle, the former Director of Creative Learning and Development at the Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce presented multiple views on whether the school system supports creatives. He discusses the argument of educationalist Sir Ken Robinson FRSA (Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts), former Chief Scientific Adviser at the Department for Education Tim Leunig FRSA and educationalist Professor Dylan William. Astle then came to his own conclusion based off the views presented by these educationalists.

Sir Ken Robinson FRSA presented a TED talk in 2007 claiming that “school kills creativity”. He argues that “we get educated out of it [creativity]”. Robinson claims that “creativity is as important as literacy and we should afford it the same status”. This implied that he does not feel that schools support creatives.

He explains in his presentation that children are “not frightened of being wrong” and that “if you’re not prepared to be wrong, you’ll never come up with anything original”. However, he goes on to explain that this open attitude towards failure does not carry through to adulthood (“by the time they get to be adults, most kids have lost that capacity [the ability to try despite potentially failing]”). Robinson states that companies “stigmatize mistakes” and as a result of companies running in this way, the national education system presents mistakes to be “the worst thing you could make”. Robinson believes that “we are educating people out of their creative capacities” due to the stigma created around mistakes by the school system. He returned for an interview on this topic in 2018, and remained with these ideas and thoughts.

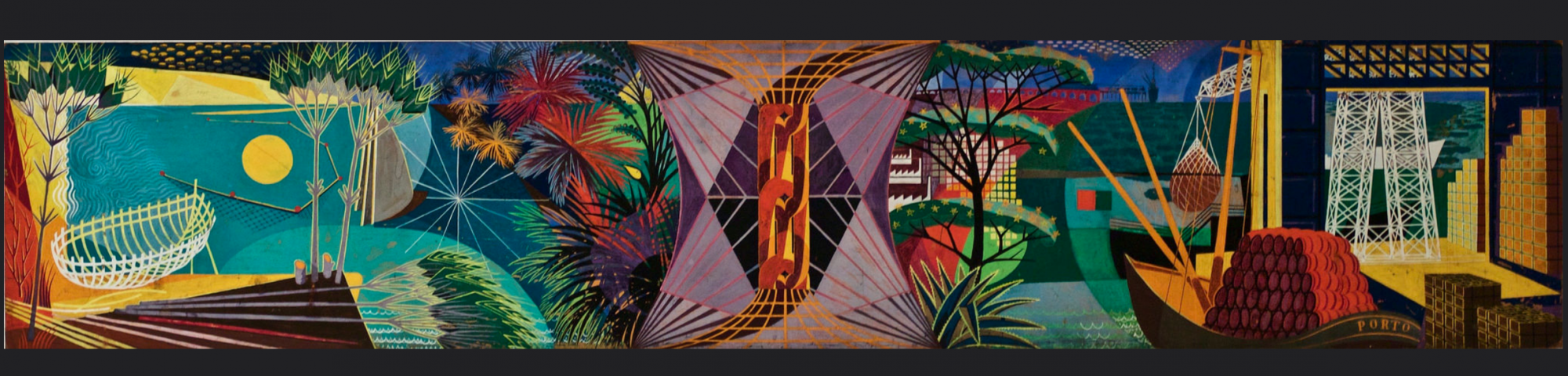

Robinson backed up his views with examples, for example Gillian Lynne, an internationally recognised dancer and choreographer. At age eight, she was pulled aside by her school for struggling to concentrate in class and being low achieving in subjects such as literacy and numeracy. As a result, she was taken to a specialist to investigate whether she had a behavioural problem or cognitive impairment. The specialist concluded that she was a dancer and just creative after observing her dance to the radio. Robinson explained that this showed how the education system was incapable of recognising the value and talent that Lynne possessed – instead perceiving it as a problem that needed medical attention and fixing.

Leunig presented a TEDx talk which challenged Robinson’s argument. Leunig believes that “true creativity… is based on knowledge which in turn is based on literacy”. He explains that because schools teach literacy, upon which all future learning depends, the education system actively cultivates creativity by providing the “foundations young people need to be properly creative”. This implies that he feels that the school system supports creatives through providing them with this knowledge which allows them to be creative.

He takes the viewpoint that people can have lots of knowledge, but without thinking creatively, no change would happen. He explains that creativity is shown through the way that knowledge is applied. Leunig uses the industrial revolution as an example. He discusses how the inventor of the steam engine Thomas Newcomen had plenty of knowledge surrounding how each component of a steam engine works, from vacuums to steam condensation. Leunig explains how without creative thinking, Newcomen would have been unable to think of a way to combine this knowledge and invent the steam engine. This implies that creativity exists only alongside knowledge.

Astle compared Robinson and Leunig’s definition of creativity in his article, which may offer some explanation for their differing views. Astle explains that Robinson’s view of creativity is based on imagination, self-expression and divergent thinking. He believes that creativity is natural and innate. Leunig’s view of creativity is based on how existing knowledge can be used to create new solutions to longstanding problems. It is heavily based on logic and the application of scientific principles. Rather than viewing creativity as something you’re born with, Leunig thought it to be highly dependent on the addition of biologically secondary knowledge (information acquired externally such as information in textbooks or lectures), presenting creativity as something you need to be taught.

The article also explores the views of Professor Dylan Wiliam. It looks at his 2013 paper Principled Curriculum Design. This paper is based upon research on skill acquisition. This research found that skills developed by training and practice (such as those skills learnt and used in school) are very rarely generalised to other areas. The research found that these skills are very closely related to the specific training. Based on this research, Wiliam concludes that “creativity is not a single thing, but in fact a whole collection of similar, but different, processes. Creativity in mathematics is not the same as creativity in visual art. If a student decides to be creative in mathematics by deciding that 2 + 2 = 3, that is not being creative, it is just silly since the student is no longer doing mathematics… Creativity involves being at the edge of a field but still being within it”. Wiliam’s view on the definition of creativity implies that schools can support creativity in some areas but not all areas.

He states that “the really important message from the research in this area is that if you want students to be creative in mathematics you have to teach this in mathematics classrooms. If you want students to think critically in history, you have to teach this in history.” As opposed to viewing creativity as a generic skill to be taught (or taught only in the ‘creative subjects’), Wiliam suggests that schools should use it as a “tool for auditing the breadth of the curriculum being offered in each discipline or subject”. This implies that he believes there is room for schools to support creatives further by increasing the amount of creativity being taught in each subject. Based off Wiliam’s views, plans such as increasing funding or other commonly-discussed ways to support creatives would not work entirely because Wiliam believes that each subject is responsible for the amount of creativity students show within that specific subject area. The curriculum or style of teaching commonly used would have to change to make a difference based off this view.

Based off these three views, Astle concluded that he believes that schools do support creatives so long as the education system provides a “rich and broad curriculum that includes the so-called creative subjects that are the visual and performing arts” and so long as the vague, varying definitions of creativity are acknowledged and understood; to be used as the starting point for curriculum design.

Journalist, public speaker and radio presenter Precious Adesina wrote an article in 2023 discussing the importance of encouraging creativity in young people. Adesina implies in this article that schools do not support creatives. She claims that “decline of the arts in education has been an issue for at least a decade”, backing the view up with statistics from The Stage (a weekly newspaper covering the entertainment industry), stating that they “reported a 37% decrease in the number of students entered for creative subjects at GCSE level since 2010”. She also states that “at age 5, a staggering 98% of children display a ‘genius level’ of creativity. By age 10, that number drops to just 30%, by age 15, it is down to 12%, and by adulthood, just 2% of us will register at ‘genius level’”. Adesina also looks at the difference between state schools and private schools, claiming that private schools support creatives more. In 2019 Sir Nicholas Serota, the chair of Arts Council England stated that “it’s currently much easier to get a broader, more creative education if you have the money to go to a private school”. Adesina uses this quote to support her view that schools generally do not support creatives.

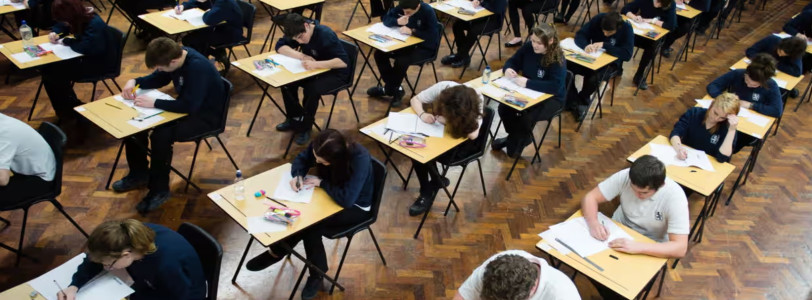

Students and teachers from my school were asked whether they think school’s support creatives, why they think that schools support / don’t support creatives and whether they think that schools could change anything to be more supportive. This is in reference to British schools in general and the education system by which they function. One student said that they do not feel that schools support creatives. They thought that the reason that schools do not support creatives is that students going into creative careers could result in a higher unemployment rate for school’s alumni. Additionally, the creative students would reflect less positively on the academic league tables compared to other subjects. They also felt that schools may perceive academic students to be ‘wasting’ their potential if they have high grades in academic subjects and choose to pursue a creative career. However, they felt that schools may support creatives in certain instances, for example creative subjects notoriously help children who struggle with academia. They felt that schools could change to be more supportive of creatives by providing work experience and opportunities to creative students as opposed to just those in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics). Schools could allow equality of access so that every student gets the opportunity to try every subject with the same treatment.

A few students and teachers shared a view that some schools do support creatives whereas others don’t. They shared views that they feel that people who work in schools or are in charge of the school system view academic subjects as superior to creative subjects. They felt that staff members made their opinions regarding creative subjects known and that this can be off putting to students who want to pursue these subjects. A student wrote that they feel that some teachers “put students down” because of their choice to pursue a creative subject. They felt that schools could be more supportive of each department in general, and everybody within a school environment should be supportive of one another and their subjects. They felt that there should be a “consistency of value across all members of [the] school community”. They shared the view that creative subjects should receive more funding. A student shared their opinion, stating that “a lack of funding leads to a barrier on student’s creativity and access to creative resources”. Another student raised the view that they felt a heavy responsibility to lead creative experiences within school themselves or else they wouldn’t happen. This is because of the lack of support they received.

A year-group lead shared their views on the subject, stating that they “do think schools support creatives by investing in teachers and resources”. They stated that they “think schools see the value in giving students opportunities to develop artistic talents in the creative arts”. They also mentioned that they believed the creative arts are often seen as an opportunity for developing the confidence of students, through being given the chance to perform and collaborate. However, they also shared that they felt that schools could invest more in high quality teachers and equipped workspaces, suggesting that they felt there was room to improve the support towards creatives further.

A core-subject teacher felt that over time the education system has shown increasing support for creatives. However, they felt that there is constant societal pressure, as well as pressure from the government, to emphasise the ‘core subjects’ (maths, english and science) at the expense of subjects where it is hard to quantify their contribution to employability. They suggested that because the focus is on these core subjects (which more frequently lead to higher, stable employability rates) it makes it very hard to support the creative subjects (as the focus is elsewhere).

They stated that they do not view the English Baccalaureate scheme as being useful because it “set up a priority list of learning”, establishing the creative subjects as the lowest priority. The teacher stated that “in an ideal world everyone would study a ‘creative’ subject to age 16”. This is actively discouraged by the hierarchy established by the English Baccalaureate and other similar schemes. They also suggested that there should be “more links and connections between the subjects overall”. However, they did not feel as though this would happen because of two perpetual issues: cost and time. They explained that in order to combat the lack of connection between subjects, more of both cost and time would be required. For example, longer school days would require the education system to have more money to accommodate this. Similarly, employing more teachers would cost the education system money. This implies that money is a real barrier towards advancement of the school system to make it more accommodating and equitable.

A creative-subject teacher shared similar views to that of the core-subject teacher, raising concern over the English Baccalaureate as well as finance and funding. This teacher felt that “most schools try to support creatives but it is not always the main focus” – suggesting that other subjects are prioritised. However, they felt that many schools are pressurised to ensure students pass the core subjects as well as the subjects involved in the English Baccalaureate, often at the expense of the creative subjects. They felt that “the government need to prioritise the creative subjects/creative industries and reflect these in school education policies”. They also recognised that it can be more expensive to run creative courses and therefore more funding is required. This could explain why some schools perhaps don’t prioritise the creative subjects as much as others. In addition to this, they felt that the careers advice provided to students at most schools isn’t sufficient when regarding creative careers.

Another creative-subject teacher felt that the school system produces a well-balanced and inclusive curriculum which develops range of transferable skills. However, they also felt that the government doesn’t fund the creative subjects as much as they could, and they felt that the creative subjects would benefit from creative subjects being included in schemes such as the baccalaureate measures. This would add more value to the subjects within the system.

Another creative-subject teacher thought that “schools provide moderate support for creative subjects, however the amount varies from school to school”. This suggests that each individual school holds a responsibility to support the creative faculty within their institution. They went on to explain that they thought that “schools like the idea of creative subjects and try to support with things… however sometimes this support could go further”. This implies that schools perhaps provide encouragement towards the creative faculties and the people residing within them but fail to support the subjects in a way that actively helps. For example, words of encouragement could be given to students within the creative subjects. This would help to build their confidence within that subject and their choices in taking the subject. However, the same school could give the creative faculties less funding than academic subjects. The funding could help to improve resources available to the students in these faculties and by providing this funding, the school would be actively working to improve the student’s experiences within these subjects. Decisions regarding specifically how creative faculties are supported within a school reside with senior management, explaining how the levels of support given to creatives can be dependent on the specific school. The teacher also mentioned that they felt that the education system as a whole needs to change. They suggested possible curriculum changes such as reducing the amount of written work required within a practical subject. This would make education less prescriptive and more suitable for a wider range of people.

Before I began research into this topic, I personally felt that the school system does not support creatives. I felt that creative faculties receive a lack of funding and that they can be viewed as inferior to other subjects – especially the STEM subjects. I feel that my views have not changed in light of this research and if anything I have found that my view is shared by many people. I also agree with Robinson in that the fundamental values that the school system is built upon stigmatize mistakes and (in most subjects) creativity as a whole. I feel that school is built upon a very specific view of intelligence that does not cater as well towards creative students or subjects. Personally, I have had a brilliant experience with the creative subjects at my school and I feel that students have been supported incredibly by both faculty staff and senior management. However, I feel that the education system as a whole leaves creative subjects and students at a disadvantage to begin with, and I have been incredibly lucky to have had the experience that I have had with these subjects. I have personally come across many people with negative attitudes towards the creative subjects. I have had people tell me that it’s both a waste of my time and my potential, from choosing my GCSE subjects through to leaving year thirteen.

Bibliography:

Do schools really “kill creativity”? - RSA (thersa.org)

Do schools kill creativity? | Sir Ken Robinson | TED (youtube.com)

The TED Interview: Sir Ken Robinson (still) wants an education revolution | TED Talk

Why real creativity is based on knowledge | Tim Leunig | TEDxWhitehall (youtube.com)

The importance of encouraging creativity in young people – The IN Group (wearetig.com)

0 Comments