During a time of isolation when it is extremely difficult to experience the culture of art through museums and exhibitions, I was delighted to see Eliasson’s offering. His exhibition, Sometimes the River is the Bridge, due to open on 14th March in Tokyo, is closed due to the current coronavirus pandemic. He has, however, allowed the public to view it online, explaining ‘in these times where we stick together by staying apart, I invite you to be among the very first visitors.’

The online exhibition has made a conscious effort to recreate the show without having the physical space to do so. You are guided through the works much like you would be in a gallery – there is a curated order to the pieces which are broken up with text which acts as the works’ description. The viewer is given a feel for the intention of the exhibition with additions of a press release, a map and a document containing the written input of a series of speakers planned to make an appearance at the show. It is difficult to understand if the images and videos of the production are also part of the physical exhibition, but online they provide a beneficial context to each piece which further evidences his pledge to make sustainable work.

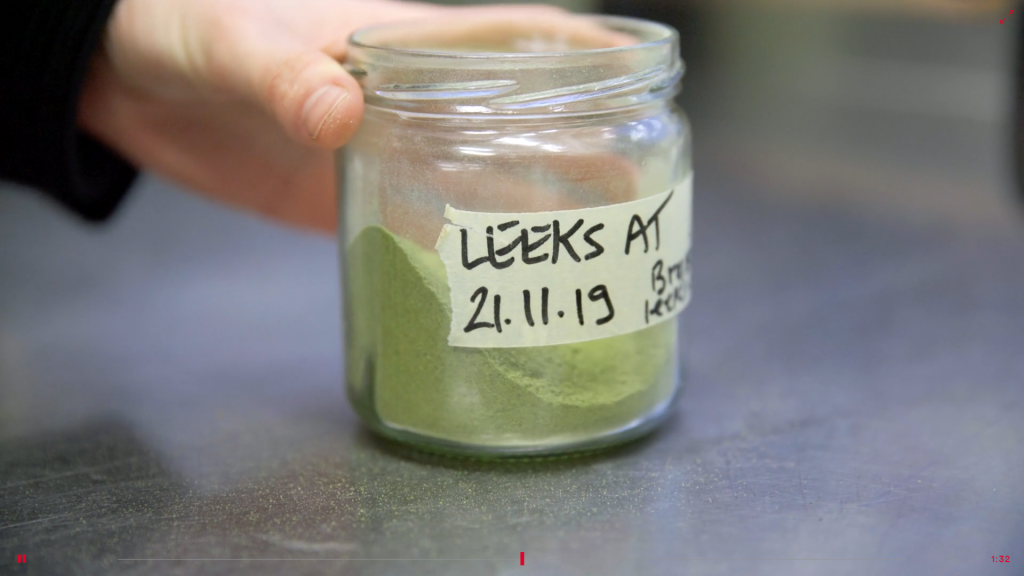

The start of the virtual exhibition gets straight to the point – Eliasson powerfully states his pledge to be kinder to the environment and it is clear this exhibition is an opportunity to improve this further. Eliasson has a consistent style of bold, colourful illusions and often bridges an ambigous gap between art and science. His conscience regarding our carbon footprint, whilst always laced into his work, is at the forefront of this show and seems evermore urgent. The virtual tour begins, not dissimilarly to In Real Life (2020), with Sustainability research lab; a simple, wooden framework displaying the weird and wonderful artefacts that inspired this line of research. This includes hanging geometric models that resemble lampshades, a wool mat knitted from the wool of icelandic sheep, jars of homemeade pigment and image postcards of these objects being used. The accompanied text brings to our attention the nature of this piece to only showcase materials which can be used for artworks, ensuring they are sustainable and promote a system of reusing waste. The exhibition sets itself apart from others with environmental themes because the work and the exhibition itself are produced sustainably. This is consistent throughout the exhibition as the works boast production from waste materials such as vegetable skins and sheep’s wool. As an artist, this made me think about the way I make work – are the materials I am using sustainable? Could I be doing more for the environment through my practice? The video captioned ‘turning leeks into watercolour pigment’ is an encouraging demonstration of a way to make artists materials from readily available products. Possibly due to the virtual nature of the exhibition, it is heavily focused on the planning and making of the works rather than the works themselves.

Memories from the critical zone (Germany–Poland–Russia–China–Japan, nos. 1–12), 2020

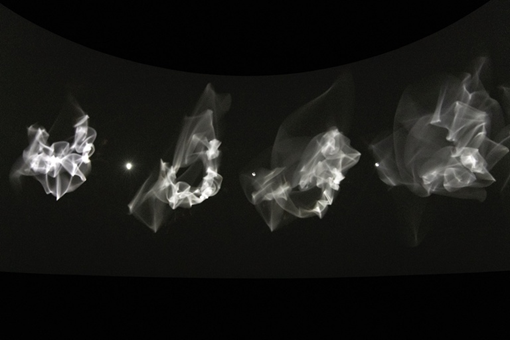

We are shown the journey that the work has taken from Eliasson’s studio in Berlin all the way to Tokyo, intentionally done without the use of planes. One piece in the exhibition really stood out to me; a beautiful series of twelve circular, black and white drawings mounted on wooden boards. As you scroll further through the exhibition, you are presented with the video Connecting cross country with a line (2013), showing the making of these drawings with one of Eliasson’s ‘drawing machines’; placed on a moving train, it maps a journey from Berlin. It shows an elegant machine made of wood which has a cavity in the centre in which a circular piece of paper is placed. A black ball of what I assume to be charcoal is then placed on the paper to roll around and create these resulting images. At this point, the works became so much more than aesthetic drawings; they were traces of our place on the earth. I think viewing this exhibition online, whilst in isolation, the work resonated with me differently than it would any other time. At this time, with many countries on full or partial lockdown, the amount that we are travelling has decreased dramatically and the streets are empty of people. All of a sudden, we are having less and less interaction with the planet and are therefore making less of a negative impact. I think this is an interesting reflection that the online exhibition allows for. As you virtually move through the show, there are consistent reminders of the works aim to reduce our carbon footprints. It causes you to consider how the restrictions prohibiting us from visiting the gallery are making a difference – how has the carbon footprint of each person who would have travelled to and from this exhibition been affected?

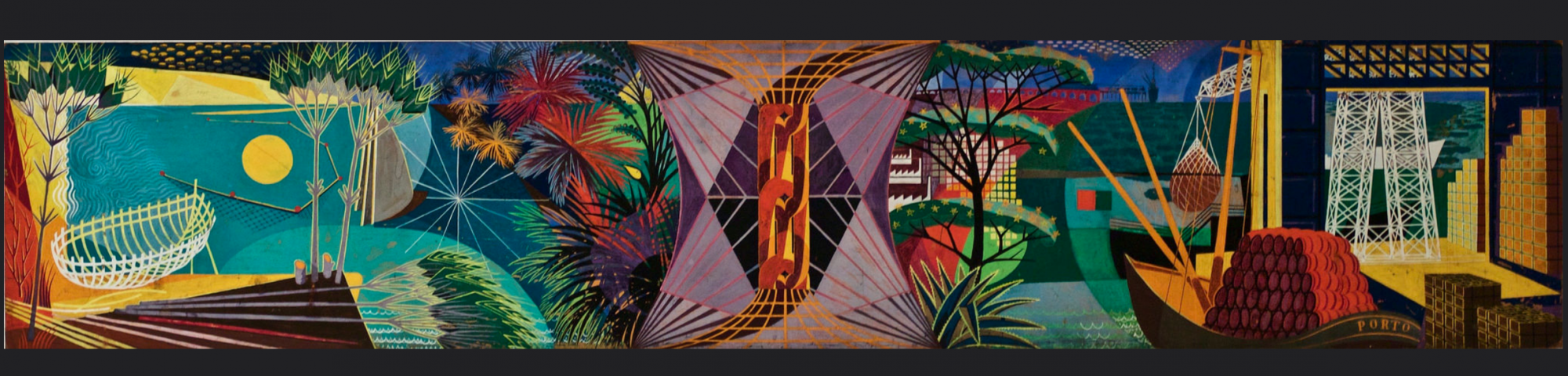

As the exhibition progresses, we begin to see a mix of Eliasson’s new and old work. The heavy works such as The glacier melt series (1999/2019) which displays the melting of an Icelandic glacier over 10 years, are broken up with more playful works, such as Your happening, has happened, will happen (2020). This piece invites viewers to enter an apparent empty room which once you do so lights ups with coloured shadows of the viewer on the wall simply created by four lights placed on the back wall. Although intended for the participation of a physical audience, this intends to bring the viewer into the work, creating an understanding that they are part of this fight against climate change. Towards the end of the virtual exhibition, there is a gallery of images showcasing each room with each work as it has been displayed in the gallery. The ability to view this as a whole sees the diversity of Eliasson’s work; the sublime snapshots of his colourful and illusional work are met with the poignant and dramatic photography of a dying landscape showing the enticing and persuasive nature of his practice. The show ends on a beautiful light piece, its namesake: Sometimes the river is a bridge (2020). The images and video show a delicate projection of a moving pool of water created by a vibrating container of water and a light; another simple demonstration of a beautiful scientific concept. The rippling circle of light on the black wall encourages quiet contemplation. It is a simple, yet effective illusion which feels as though it is slowing down time, an interesting contrast to other works in the collection. The virtual tour accompanies this last piece with a quote from the head of exhibitions, Caroline Eggel, who explains this show to be a critical time which will see a more sustainable future for their work.

Sometimes the river is the bridge, 2020

Sometimes the river is the bridge, 2020

Overall, I really enjoyed this virtual exhibition. In such times, it has been refreshing to view art which is passionate about caring for our planet. When the show could sadly not go ahead, I believe the decision to publish it online was a brilliant way to make the best of such a situation. What has sparked my interest the most is witnessing how the impact of an exhibition which is planned and curated to send a certain message can change with the context and situation it is viewed in. Whilst the world is experiencing sad and difficult times, the planet is taking this time to heal itself; with records showing less pollution as the human population stay indoors. Sometimes the river is the bridge is a powerful exhibition which, whilst produced before a global pandemic begun, now sits within a new place in culture – one that we can enjoy from the comfort of our own home.

0 Comments