31 January 2020 - 11:00PM

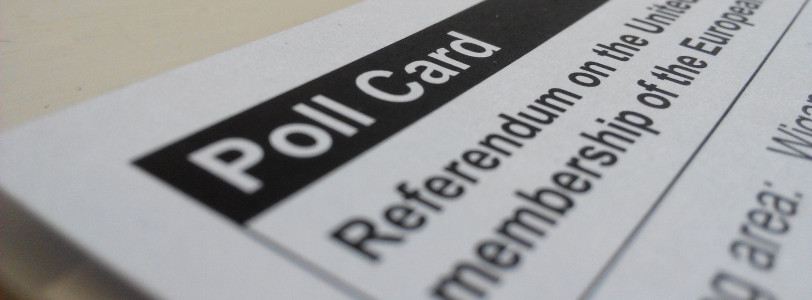

This date and time represents a watershed moment for our country, as we left the European Union. Whether this was for better or for worse is a point of contention that is outside the purview of this article, but even the most ardent ‘leave’ voter must concede progress has been much slower than anticipated. YouGov data reports that seventy percent of the public believes they are suffering from ‘Brexit fatigue’, but these voters may be feeling revitalised after the ratification of Priti Patel’s ‘Nationality & Borders Bill’ – although it is now much more apt to refer to the legislation as ‘The Nationality & Borders Act (2022)’ (‘the N&B Act’).

The political slogan ‘take back control of our borders’ became ubiquitous during the lead-up to Brexit. The 'Vote Leave' group made it a core tenant of their campaign alongside better immigration controls, but it would endure long past this and featured as part of the manifesto of the incumbent Conservatives. The N&B Act may have come over two years later but represents a step towards ‘taking back control’, but at what cost?

Well, after MP, activist and public outcry it is evident that this legislation is highly controversial. The outcry centred around the provisions of non-refoulement and pushbacks contained in the act – the latter of which was abandoned by the government in the pre-action stage before the bill was passed. Yet, it was too late to avoid the spotlight, alongside the act’s potential political, legal and human rights costs. I’ve discussed the three dimensions of the act with experts in these respective fields; Dr Kelly Staples (Uni Of Leicester), Hazel Blake (Law Society), Michael Marziano (Westkin Associates) and Steve Valdez-Symonds (Amnesty International) have all lended their expertise to calculate the political, legal and human rights cost of the act respectively.

The Human Rights Cost

The N&B Act’s controversial provisions ensured it would not go through the legislative process quietly. Indeed, the act permeated the political zeitgeist and was a point of contention outside of Westminster. One of the salient reasons why it attracted this attention was because of its potential human rights costs.

The Refugee Convention (1951) (‘The RC’) and The United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHCR), are rightfully considered to be two of the sources of authority when it comes to asylum seekers’ rights. There is little wonder then that they were so frequently referred to when calculating the costs of the act, and something of great importance to human rights groups concerned about potential violations. Amnesty International is the world’s leading human rights organisation, and at the centre of their response is Refugee And Migrant Rights Programme Director at Amnesty UK - Steve Valdez-Symonds.

What’s the problem?

“I feel it’s important to realise this is a bill of two-halves and make a demarcation between the two” says Valdez-Symonds, who explains that it can be thought of as having both an asylum and nationality side.

“The problem with the asylum half cannot necessarily be reduced to any one particular provision per say, but rather the underlying intent behind these provisions collectively, which is why this is so problematic. Only when viewed collectively can the full impact and cruel irresponsibility of the act be truly measured. The bill broadcasts that asylum seekers are not welcome and if they decide to try to seek asylum here, they will not receive the same standard of care, safety nor dignity that they would be afforded elsewhere. They can expect the government to take every chance to imprison, make them destitute or expel them. This sets a dangerous precedent internationally because if other countries were to act in the same way, there would be no place of safe refuge for those who are fleeing their countries for whatever reason(s).”

This should come as no surprise to those who had followed the act throughout the legislative process. After all, much of the outcry was focused upon the asylum provisions of the act and its ramifications. Something less-frequently discussed though were all of the various nationality provisions. Here, Valdez-Symonds believes that “... the nationality provisions found in the act will largely do real good in finally restoring citizenship rights that have wrongly been denied to those who deserve them over a number of generations and decades.” Whilst one may be ready to finally breathe a sigh of relief, he continues that “even among these provisions the government seeks to deprive groups of their rights – particularly stateless children born here, people stripped of citizenship or will be stripped in the future by the home secretary.”

Whilst most of the collective attention was preoccupied with provisions such as the offshore processing, it’s starting to become apparent that the act may just incur greater costs than had been initially anticipated. One may reasonably wonder which of the other lesser discussed provisions of the act posed a problem, and which provisions may have escaped the scrutinous spotlight whilst it was being shone upon offshore processing.

Valdez-Symonds firstly addresses a common understanding of what offshore processing actually is. “The term ‘offshore processing’ refers to conducting assessments of asylum claims outside your country. The UK has no intention of assessing claims of those who they expel as part of their deal to Rwanda, the aim is instead that the prospective asylum seeker will become entirely the responsibility of Rwanda. Rwanda does not appear to have any processing centres nor did it process people in their deal with Israel, these people instead ended up back in the hands of people smugglers.”

Assessing some of the lesser discussed dangers that are found in the act, one stood out. “The government forced the bill through the legislative process to unilaterally redefine the [Refugee] Convention, allowing them to deny refugees protections using definitions that are plainly wrong or more restrictive than the already existing interpretations.”

Given the scandals that have plagued the prime minister as of late, and all of the talk of accountability, surely such a flagrant unilateral manoeuvre should be something that the public should be talking about? Alas, Valdez-Symonds assures us that there are parties which are holding the government to account. “The government however insists that they are acting consistently with The Refugee Convention (1951). Yet, the Commons and Lords are ‘ping-ponging’ the bill between themselves because they argue it’s not. The act was roundly condemned by leading judicial and legal experts domestically and internationally; UNHCR, UK Supreme Court ex-members, Home Office ex-officials, lawyers acting for the government and of course Amnesty International.”

Lessons from Australia

The N&B Act is not the first of its kind however, and borrows heavily from the measures implemented in Australia, who adopted similarly controversial provisions like ‘boat pushbacks’ and ‘The Pacific Solution’. These were largely considered to be ineffective which led to critics believing the same will be true here, particularly the government’s hope that the act will hopefully deter people smuggling organisations. Valdez-Symonds explains however that this is not only unlikely to be true but even counterproductive; “this legislation would cause fear in asylum seekers and terrorise rather than safeguard these people. This is a particularly dangerous consequence because it increases the likelihood that asylum seekers avoid the authorities for fear of potential reprisal. They will likely lie low, which is just counterproductive, because it increases the chance of them turning to smugglers who are less likely to face accountability.”

This however is not the only lesson which this country can learn from the asylum system of Australia. Another criticism levied against their policies was that the government used refugees, overblowing how many of them were coming by boat in order to make political gains. Valdez-Symonds on Twitter composed a thread discussing how visibility often will inform these policies, Boris Johnson’s government seems to be playing up the issue very similarly to Australia’s John Howard.

“The rhetoric and contrived excitement of crossing the channel by boat is a long-standing phenomenon. Asylum seekers have been forced to resort to that measure for years and if not this then something else - lorries, trains and even freight containers are just some of the dangerous ways people get to the UK. Even in years where the number of asylum seekers crossing the channel by boat increased from before, this did not equate to more asylum seekers entering the countries and in some years it even decreased. Nothing had fundamentally changed, but it made for sensationalist reporting and inflaming the public.”

This isn’t necessarily a partisan issue either, but rather something which both major parties are guilty of. Conservatives are certainly guilty of exploiting the issue but in a similar vein so are the Labour Party. “Whether it’s Labour or Conservative, the salience of immigration has been raised by all political parties. Labour’s critique of the bill often centres around it being ineffective rather than actually being wrong.”

Australia is not the only evidence that we have to draw from either, we can also refer back to the aforementioned Rwanda-Israel 'Voluntary Departure Scheme'.

“Israel and Rwanda’s offshore processing arrangement attests to the notion it will not deter smugglers. Rwanda’s processing centres simply regenerate the conditions that facilitate the smuggling of people, often asylum seekers turn to smugglers to escape but instead are smuggled through the whole of Africa. The conditions which enable smuggling in the first place are what need to be addressed before all else, because currently it feels like it’s all about the optics.

Valdez-Symonds uses Ukraine as an example of how the government only took action when necessary. The Conservatives initial response was to maintain distance from the crisis and to simply step aside. “This only changed when the crisis gathered widespread media attention and public desire to do more. Yet, it runs much deeper than their initial response and into their begrudging response to this crisis. Ukrainians now have two routes to visas yet neither of these actually appear to be working effectively, instead they have deterred thousands of refugees from seeking safety from persecution here in the UK.

One wonders why the first instinct was to act with suspicion, hostility and in some cases even with hate. Indeed, the government appears to only assuage criticism rather than address the needs and rights of refugees.”

Humanising The System

Evidently, there is both a clear desire and need to humanise the way that our asylum system operates – as Valdez-Symonds argued on Sky News, where he made the case for the system to be reformed in order to be more “effective, efficient and humane”. One may subsequently wonder then exactly what changes need to be made in order for this to happen? Valdez-Symonds feels “... attitudes expressed by government and a minority of the public must change. We need to take our fair share of refugees like we agreed to do so in The Refugee Convention (1951), yet it appears we are reluctant to do so and hesitant in respecting the rights asylum seekers possess. The current system’s knee-jerk reaction is to deny asylum and this itself is fraught with proven problems. There is a backlog of asylum applications and this has come at great financial cost to try to deal with.”

An example must be set by the government before any tangible changes to the existing asylum system occurs. Johnson’s administration has a choice to make whereby a conscious decision must be made by them. “They have to decide to inform the wider public and build upon their strong commitment to offer support, but so far all they have done is exploit and further encourage suspicion, misunderstanding and hostility. By doing so, they weaken (if not wreck) our capacity to support refugees and sustaining the attitudes that drive its policy agenda.”

Ultimately, a lot of work remains to be done before we see either de jure or de facto changes to asylum. Unfortunately, until that point there will be unavoidable human rights taxes that will have to be paid with the N&B Act.

The Legal Cost

Unfortunately, the bill is much longer than many of us may have expected and it includes other costs. The potential human rights violations are one cost but another item which needs to be settled are the legal costs of the N&B Act.

Although the bill may have passed and it will now no doubt overhaul the asylum and immigration system, this is certainly not the end of the story, with rumblings of inevitable legal challenges in the near future. In fact, they have already begun as lawyers seek to challenge what they believe is unjust legislation. Two of the parties who’ll play a pivotal role in this process are immigration lawyers and The Law Society. Michael Marziano of Westin Associates and Hazel Blake of The Law Society have offered insights on the N&B Act’s legal costs and potential future challenges.

How legally sound is the act?

The crux of the discourse surrounding the act appears to be around how legally ‘sound’ it truly is. Yes, it has been ratified and made into law but does this necessarily mean this is the end of the road? Hazel Blake of The Law Society explains it certainly this is not the case and if anything it is just the start. “The bill is legally ‘sound’ in the sense that it is now a law and has become an official act of Parliament, but its impact on migrants, international law and our legal system leaves it open to future challenges.” Indeed, challenges have already begun, and Michael Marziano of Westkin Associates informs us existing challenges that are underway by the likes of Detention Action and Freedom From Torture.

The act does not violate the law insofar as it instead bends it in order to make its provisions admissible. The Dublin Regulation is an example of what was considered to be ‘safe’ – the N&B extends that. Marziano delves into the nuances of these pieces of legislation to help us better understand them. “The Refugee Convention (1951) does not prohibit removal of an asylum seeker to a safe third country. The Dublin Regulations in EU Law provides for removal of asylum seekers to other safe third countries, typically to countries within the union and that they may have travelled through on their way to the UK.” Whilst the act appears to be morally ambiguous it technically does not appear to contravene any laws, instead it “... widens the parameters of what can be considered to be a ‘safe’ country, broadly allowing it to mean any country that is willing open their borders and to accept asylum seekers – Rwanda for example.”

Compatibility With Conventions

The Refugee Convention

A word that you may have come across throughout the online debates over the act is ‘non-refoulement’. A lot was made about the compatibility of this provision of The Refugee Convention with the N&B Act. Baker explains that “non-refoulement means an asylum seeker can’t be sent back to a place where they face danger.”

Rwanda’s track record with human rights however has historically tended to be, shall we say… mixed. Blake recognises that yet informs us that the bill makes it harder for asylum seekers to avoid Rwanda, despite it seemingly being a place where they would face danger and running contrary to non-refoulement. “There’s a number of ways in which it does so, but there are three things that make it harder for refugees; a two-tier system, increased burden of proof, reduced ability to appeal and changing what constitutes a ‘particularly serious crime’.”

Maraziano corroborates this account and explains that if it is indeed true that Articles 32 and 33 of The Refugee Convention are being violated, then it could spark legal challenges.

Human Rights Convention

Article 3 of The Human Rights Conventions has many speculating if there is a human rights breach, should asylum seekers be sent to other countries to process their application or apply for citizenship. Marziano asks; “... will one be subject to inhuman or degrading treatment in the country they’re sent to? A holistic approach is taken where factors such as authorities, police and public reception are assessed. This could be a valid legal basis for challenge if it can be proved these conditions may be in violation of Article 3.”

One of the core tenets of the convention does however allow one to appeal any decisions that are made. Blake warns though that “... going forward, this will be much more difficult to do now the act’s passed … either by removing stages of appeal or fast-tracking cases so less time is available for them to prepare. In 2015, this was found to be unlawful as it was structurally unfair yet the act reintroduces this measure.”

Marziano discusses what happens in the interim stage between an appeal and the decision being made. “If a person makes a challenge against a removal in the courts and they are also liable to be detained, they can instead apply for release in immigration bail which may entitle them to access certain supports. This may however become more complicated under the new legal regime.”

The potential legal challenges

Ultimately, the act may have recently received royal assent and become law but it treads on thin ice. Even in the initial legislative process “... there was a pre-action letter submitted in opposition towards the ‘pushback’ policy to the Home Office, and the government abandoned the policy rather than take it to court”, Blake says.

However, this may have only been the start, with other organisations having declared their intentions – Detention Action and Care4Calais are just two organisations that immediately came to Marziano’s mind. These will likely serve as the larger ‘test cases’, so “... other cases will be stayed behind these whilst the courts determine how the law should be applied - something which can take years if not even decades.”

One thing however is for sure and that is the clear determination to deliver justice by those such as Marziano and The Law Society.

“As immigration lawyers, we must adapt to frequent overhauls of the asylum and immigration system - there will certainly be changes and we will simply have to familiarise ourselves with these so that we can help ensure justice is achieved”, says Marziano.

“The Law Society hopes that challenges are however taken seriously by the incumbent government, rather than being dismissed as politically motivated, which just creates hostility towards these lawyers. The ability to challenge a government is a core component of the legal system and must be respected”, insists Blake.

The Political Cost

Westminster is the beating heart of politics in this country, and of course it is here where the act was thought-up, drafted and passed.

Naturally, there will therefore be political costs associated with such a controversial piece of legislation. As somebody who studied politics to a postgraduate level, however, I can attest to the myriad of concepts, theories and explanations which exist that make calculating this cost all the more difficult.

Dr Kelly Staples (University Of Leicester), is an expert in human rights, migration, and statelessness. She is well placed to comment on the political cost of the N&B act, and how its ramifications may play out in the political sphere.

Stuck between a state and a hard place

Dr Kelly Staples is an expert in many areas but one which is particularly relevant to us is ‘statelessness’. This is because the act places more people at risk of becoming stateless and risks jeopardising the UNHCR’s mission to end statelessness, but what actually is the often-lauded concept of statelessness? Staples explains:

“The Convention Relating To The Status Of Stateless Persons (1954) offers the canonical definition, which is that; ‘a person who is not considered as a national by any State under the operation of its law’. This suggests that one is clearly either a national, or stateless.”

As you have probably gathered throughout this article however it is rare for it to ever be this simple. Unfortunately, the reality of this is that “there are a number of questions which must be answered first. Let’s take the phrase ‘one who is not considered …’, well – considered by who and why them exactly? This is as much a matter of politics as of law.”

The N&B Act puts more people at risk of statelessness but calculating this risk is another matter entirely. “Often, calculating a person’s risk of statelessness is obfuscated by political factors which play a role. This is before we even begin to consider other auxiliary factors such as The Nationality & Borders Act.”

Having more people be made stateless would also add to the theoretical quagmire that has been dubbed ‘The Refugee Problem’, which comes with a number of ethical considerations when trying to resolve.

“What constitutes an ethical consideration depends on the ‘lens’ through which we look at the problem. The theory of ‘cosmopolitanism’ is a popular one and cosmopolitans believe that everyone is entitled to equal respect, consideration and treatment regardless of their citizenship status or other considerations. This is all very well and good in theory but in practice we do often see that the circumstances do matter. Yes, safety and security are absolutely fundamental human rights but they are made difficult to obtain, and asylum seekers are not treated in ways that can be accurately and neatly described by any theory.”

This and statelessness are two of the main problems which are being tackled head on as part of the UNHCR’s efforts to ‘end statelessness’.

The UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) is championing a mission to end statelessness throughout the world. ‘#EndStatelessness’ makes for a catchy hashtag but such an ambitious mission will inevitably encounter hurdles which have to be jumped over on the way.

“One of the main challenges which make ending statelessness difficult is actually the states themselves. So, states see their asylum and immigration policies as being absolutely fundamental to sovereignty; however much control they have over these is almost a sort of indication of their power and their status. We’ve seen states exercise this power to make policies increasingly restrictive through measures like The Nationality & Borders Act.”

Staples goes on to explain that not only are there tangible challenges but theoretical hurdles to jump too. The UNHCR’s ‘#EndStatelessness’ mission is admirable but one which may just be inherently flawed.

“Statelessness is often thought of in binary terms which leaves very little room for theoretical nuance. Take Shamima Begum, who our country denied citizenship insisting she was entitled to it in Bangladesh - Bangladesh however exercised their aforementioned sovereignty and also refused to grant citizenship. This meant she was left in the limbo of statelessness.”

What impact will the N&B Act have on this?

The act will likely exacerbate the existing problems.

Staples tells me of campaign groups which have identified particular areas that will be adversely affected. One is “... child statelessness, where parents have to make good faith efforts under the new act to obtain another nationality first before they can apply for citizenship for their child.”

You may remember reading the news that citizenship could be stripped without notice by Priti Patel. Thankfully, this measure has since been challenged, but people with dual nationality are still at risk as “... the government can insist they have citizenship in another country.”

A fear of these campaigning groups is the repeat of the injustices faced by the Windrush Generation. Staples explains that this fear is not unfounded as “a lot of research suggests that there is a racialised element to these policies which means ethnic minority groups stand to be disproportionately affected.”

The Cost Of ‘Taking Back Control’

At the top of this article the question was asked of what the cost of ‘taking back control of our borders’ is. Evidently, the cost is high.

Whilst ‘take back control of our borders’ may have made for a quotable soundbite in the lead to Brexit, these six words cultivated a culture which has enabled things including the ratification of this polarising N&B Act.

One thing is for certain though and this is we cannot allow asylum seekers to be left to pay these costs.

About The Contributors

I would like to take this opportunity to thank and tell you a little about the four contributors to this article, all of which are experts in their respective fields and were kind enough to allow me to interview them.

| Steve Valdez-SymondsSteve Valdez-Symonds is Amnesty International’s Refugee & Human Rights Director within The UK. Valdez-Symonds areas of expertise include forced migration, immigration, asylum and citizenship, having worked on successive immigration bills and writing responses to government policy for Amnesty. Amnesty needs no introduction but it is one of the preeminent human rights organisations in the world, with in excess of ten million supporters worldwide. |

| Hazel BlakeHazel Blake is The Law Society’s policy advisor for human rights, constitutional and administrative law. The Law Society is a professional association that both represents and governs solicitors throughout England and Wales, and helps shape reform in the sector. |

| Michael MarzianoMichael Marziano of Westkin Associates is a seasoned immigration lawyer having practised since 2005. Marziano is OISC Regulated (Level 3) and is accredited under The SRA Immigration & Asylum Scheme, and has assisted clients in virtually every imaginable type of immigration case which one can imagine. Westkin Associates in Mayfair, London is an incredibly respected firm specialising in immigration cases, drawing on eighteen years of experience and having developed an impressive roster of solicitors to boot. |

| Dr Kelly StaplesDr Kelly Staples of The University Of Leicester is a expert in human rights, migration and statelessness. A former lecturer of mine, I can personally attest to her expert knowledge and teaching abilities alike - should this article have piqued your interest in the subject I would highly recommend her chapter in Understanding Statelessness. |

0 Comments