A landscape painter by trade, today Edward Lear is perhaps best known for his nonsense poetry (“bosh”) and his tales of strange creatures which travel to distant, improbable lands. But what inspired his poems – about The Jumblies, who “went to sea in a sieve” in search of the fabled Chankley Bore, or the fantastical Scroobius Pip, an oddball animal which eschews classification – can be traced back to Lear’s own profound sensitivity towards queerness and belonging.

How pleasant to know Mr Lear!

Who has written such volumes of stuff!

Some think him ill-tempered and queer,

But a few think him pleasant enough.

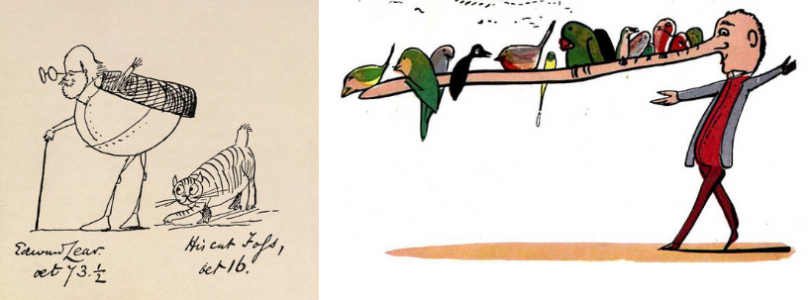

Lear supposedly co-wrote “How pleasant to know Mr Lear” in 1879 with a Miss Bevan, whose father was Vice Consul in San Remo, where Lear finally settled in a sort of self-imposed exile. As a gay, closeted, epileptic man in Victorian England, it comes as no surprise that he felt most at home on the road.

At this time, “queer” neither referred to sexuality nor gender identity, but simply a mark of difference or otherness, something not quite normal, perverse even. Indeed, Lear’s admission that “some [may] think him ill-tempered and queer” was somewhat of an understatement. As far as Victorian medicine was concerned, epilepsy was wrongly thought of as a condition borne out of sexual deviance, as a physical manifestation of what was considered a moral failing.

Acutely aware then of his own queerness and bodily foibles (Lear also wrote scathingly about his appearance, particularly the size of his nose), his nonsense poems regularly mirror anxieties of otherness and difference, often featuring eccentrics punished for their non-conformity. For example, his limerick about the unfortunate “Old Man of Whitehaven”:

There was an Old Man of Whitehaven,

Who danced a quadrille with a Raven;

They said – “It’s absurd, to encourage this bird!”

So they smashed that Old Man of Whitehaven.

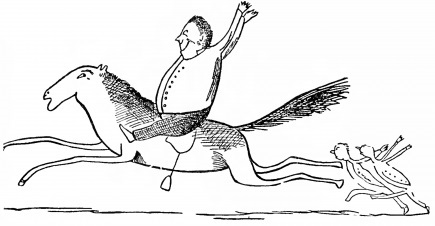

Whatever it is they find abhorrent about square dancing with a corvid, the people of Whitehaven do not take kindly to it at all. Instead they resort to "smashing" the culprit as punishment for his actions. It is unclear, however, given the absurdity of the scene, what crime has been committed, if any at all. Likewise, we wonder if similar circumstances provoked the “Old Person of Basing” to escape his home on horseback:

There was an Old Person of Basing,

Whose presence of mind was amazing;

He purchased a steed, which he rode at full speed,

And escaped from the people of Basing.

For 1984 author George Orwell, who wrote briefly about Edward Lear’s limericks, the “they” of the poems represent “the right-thinking, art-hating majority” and society’s populist leanings towards bigotry and intolerance. In such a world, to be different is to be criminal; and queerness of any kind, let alone in terms of sexuality, is considered a threat. No wonder the Old Person of Basing turned tail and fled (after all, his “presence of mind was amazing”).

If nonsense poetry is another way of testing the logic of our world – an upending of sense to probe at its boundaries – then it is also a means for expanding it. In Lear’s most enduring poem, “The Owl and the Pussycat”, he celebrates the most unlikely of pairings. The poem is a matrimonial fantasy, but one free of distress and the hetero-Victorian expectations Lear himself used as cover (“I anticipate the chance of a Mrs Lear”, he once wrote, half-ironically, “in 40 years hence”).

Pussy-Cat proposes to Owl in their beautiful pea-green boat, urging that they have waited too long already for this moment: “O let us be married! too long we have tarried: / But what shall we do for a ring?" After securing a ring from a Piggy-wig for the price of one shilling, Owl marries its natural predator, a feline with a soft-spot for honey and song.

The pair dance by the light of the moon despite their differences; something we should all encourage. Next step, dancing a quadrille with a raven...

0 Comments