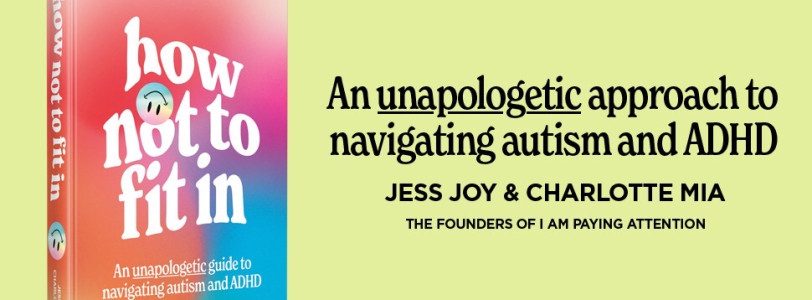

‘How To Not Fit In: An Unapologetic Guide to Navigating Autism and ADHD’ by Jess Joy and Charlotte Mia is a perfect way to educate yourself about neurodivergence!

Charlotte Mia and Jess Joy, founders of ‘I Am Paying Attention’ and now authors of the newly published ‘How To Not Fit In: An Unapologetic Guide to Navigating Autism and ADHD’, have amassed 100,000 followers on Instagram and counting and most importantly have a welcoming presence. Meeting Mia and Jess was a pleasure! The interview covered a breadth of topics from what they like to do to decompress from stress to why they think capitalism negatively impacts neurodivergence to what their opinions are on masking, and we discussed many more intriguing topics like these. They were able to tell me about the importance of their book and how it is meant to inform anyone about ADHD and autism whether it is for themselves or someone else they know. And why the book has helped them to overall produce an amazing opportunity to broaden awareness of neurodivergence but also be pioneers in contributing to creating a comfortable environment in which the next generation feel welcome and settled in. This interview delivers messages of compassion, empathy and kindness necessary for us in society right now. Enjoy!

Generally, there’s a sense of women being underdiagnosed and the more intersectional in society the more underdiagnosed they are in terms of autism and ADHD. In terms of this, where do you feel like more attention should be placed such as maybe schools, universities and/or the workplace in terms of spreading knowledge through these avenues?

Jess: Firstly, I'd say that in the last few years, obviously we started our account a few years ago now. I’d say that whilst it’s obviously a positive thing that the conversation has grown and become more mainstream. I’d say we’re particularly aware that a lot of people in the space now are white women. I think that’s something that we’re very conscious of. From the very beginning of creating our account it was like, okay yeah, we’ll share our experiences, but we are very aware that our experiences aren’t like. We don’t want to represent ADHD and autism in its entirety, you know. We are very aware that white voices are being amplified and I think we're doing what we can as a brand, as people, as authors to use the platform in the right way. We’ve worked with people to sort of shine a bit of light on how, for example, the cultural background might influence them to navigate things like neurodivergence.

Mia: I think whilst we are able to spread awareness the problem is systemic. I think we need to get into school, as early as possible, to be able to raise awareness at such a young level that it means that people, regardless of their background, are able to succeed in places like university.

Jess: Just access the support they deserve.

Mia: Yeah, exactly. I think at the moment, there is that lack of awareness from as young as even when you’re in pre-school. I think you’re naturally more disadvantaged from the get-go.

Jess: I think we’re trying to do what we can not to just have the conversations, but we’ve recently also moved into I guess what you would call workplace training. Me and Mia do

something called a ‘Power Hour’. It’s Basically just an hour doing some basics around neurodivergence. We’re encouraging wider awareness and educating people on making the workplace more inclusive.

Mia: Aimed at the employers as well, not the employees. Typically, a lot of the support is aimed at the people struggling so what we want to do is start to give the toolkit to those who are responsible for neurodivergent employees. And put the responsibility on the shoulders of the people in charge rather than the people struggling.

Jess: Exactly, yeah. I think through all of the themes that we talk about in the book, and in general, I think it just boils back down to it being systemic and I think that’s obviously a very nuanced conversation. But, yeah, I think we’re trying to tackle that by education and then trying to use the platform to position ourselves to hopefully change that.

Do you feel as though if either of you were neurotypical would your bond have been harder to form?

Jess: Yeah, I think so. I think we connected so easily because we work in pretty similar ways. There are several things that we're quite different in: several areas. But I think, we just really understand each other on quite a deep level and when it comes to the support we provide each other. I think quite intuitively understand what the person needs without them having to communicate it. Obviously, communication requires energy, right, yeah.

Mia: More generally, speaking it as well also highlights the importance of neurodivergent friendship. And the fact that, to have someone that really understands the way that your brain works, and even beyond being neurodivergent being disabled, being able to be with someone who understands why you might have anxiety about certain things and why you struggle to go to a bar or restaurant and why you don't want to go to a social event. Having someone that really understands on that level is so important. Because i think both of us spent so many years trying to fit in with friendship groups where we can go out and go to these loud social events and we can fit in. But the reality is it wasn’t comfortable for us and things like, even getting the train today, it’s like being really aware of the fact that, that it does take a lot of energy, that is stressful. How can we support each other? And the reality is if one of us is neurotypical, yes, we might be able to still support but it’s not that sort of reciprocal thing, is it? I think that makes our bond probably a lot stronger.

Jess: I think particularly with being autistic, that is really huge for us, and I think that is very relevant. Well, I mean obviously just being neurodivergent is just who we are, but I think being autistic like the way we process the world, navigate things very deeply. Yeah, I think the way we navigate the world and the way we process things on such an intense level really means that, yeah, it would be very different to be as close to someone who doesn’t share that.

In terms of Chapter 2: 'What Is Neurodivergence?' Did you feel you had to question your internalised or maybe imposed definition of what is normal? And if you did experience that, how did you navigate challenging and improving your definition?

Jess: Essentially, I think we did have to unlearn a lot of standards that perhaps initially we weren’t aware were there. It basically required a lot of unlearning and then relearning and i think that was sort of a task that involved dropping a lot of shame, you know, for a really long time, expecting ourselves to be able to manage things but other people in our lives, you know, people that we’ve worked alongside or even people that we maybe see in our social media feeds. Think really understanding ourselves and the way that we work better. As a result, being able to adjust what we think is realistic for our us.

Mia: I think also we’ve had to unlearn a lot of ableism. I think that it's a deeply rooted in our society, we suddenly had to come terms with the fact that ADHD and autism is classed as a disability and also Jess had a lupus diagnosis back in 2014. So, I think Jess came to terms with the term ‘disabled’ a lot sooner. But there was a still deep-rooted ableism within us and around what we could manage.

Jess: Sorry to interrupt you, but to be completely transparent, I feel like it’s still there to some extent. As a very vulnerable example, I was supposed to get the train yesterday and it did in fact involve a change in London that, yeah, I struggled with quite a lot. I find the busy environment and the unfamiliarity of it really difficult to navigate. And I essentially just ended up completely sobbing and not even being able to get on the train, so I had to be driven to my destination which was a few hours away. The way I still feel about those kinds of situations, I can still notice that shame and embarrassment there.

Mia: We’re always very quick to say yes. If something is expected of us. Yes, we can manage going on the tube, changing here, changing there. But its like, in reality, if we are completely independent on ourselves, that those put a lot of stress and strain on us. Whilst if can maybe manage that in a while, I think ableism pops up quite often for us, where we realise that for a huge part of our lives, we’ve been telling ourselves that: ‘yes, we can do these things’; and our valuing is based around that. But its just an endless ball of just like how do we pinpoint sort of: is this something I need to unlearn?

Jess: It's basically we had the default definition for a long time and it’s basically now reassessing whether that should be the default or not. So yeah, a very complicated context.

Mia: It's been around two or three years since our diagnoses or realisations. But we’re still trying to figure out whether what we can manage is realistic and there’s a lot of shame around that.

What do you want readers to get from reading part 1 of ‘What Is Neurodivergence?

Jess: I think essentially like, although in a society that functions the way it does, labels and medical diagnoses are really important for our people to be able to successfully be granted accommodations or adjustments. I think our thoughts are that it's really important whether it is something you’ve realised that being able to get in touch with yourself a little bit more, and without, you know, too much shame covering the questions that you ask yourself. Yeah, sort of about adjusting what you expect of yourself and whatever label that has attached to it like. We both definitely agree that it’s important to navigate the world with as much peace as they possibly can.

Mia: I think also one thing we try to achieve throughout the whole book but probably with that chapter more so is being able to explain it in a way whether you’re neurodivergent or not it gives a real sort of rounded explanation and experience to as many people as possible because i think whether you're neurodivergent or whether have a friend who is neurodivergent or whether you're curious or has a child with neurodivergence, wanted it to feel like an easy book to read regardless of whether it was something you’re looking into. Because I think what we’re going for is really as much awareness as possible. This isn’t a niche thing. We really wanted to write it in a way that gave a general understanding to someone even if you weren’t autistic or have ADHD.

I appreciated reading about your perspectives on high and low functioning labelling of disabilities. I think that’s something that should be talked about more especially amongst those in the disabled community. What do you think?

Mia: We've had a few conversations recently around communicating support needs and focusing on your level of functioning, which is kinda ableist as we all function in different ways. In today's society, some of us need more support than others and I think it doesn’t whittle it down to what you can see as a person: ‘oh, they’re functioning. Oh, they’re not’. The way that society is built, I might have more support needs in some areas than Jess and vice versa. Obviously, there are going to be people that are going to need way more support than both of us put together. It means nor one of is functioning better or worse because that’s not the reality, the reality is society works better for some people than others.

Jess: And I also think when I think about when people would look at us and have conversations with them such as about the book. For example, when I was in an uber talking about the book, if I heard comments like and people are like you look a bit too normal to have ADHD or autism. I can't hold it against them because they are kinda just a product of the way society thinks. But at the same time, I don't think we should expect a certain thing from somebody just by looking at them. Obviously, there are people with higher support needs than us and I would also the same quote applies to them. There are people in our community who are nonspeaking and there are a lot of ppm who assume that because they don't use verbal communication means that they don't understand. Not that intelligence is really correlated with worth at all. But I think they assume that people who are non-speaking aren't intelligent. Whether they are or they're not it's not important.

Mia: It's obvious that it’s a product of ableism. The fact that the saying, ‘you don't look autistic’ even exists because it’s like ‘we have a vision of what autistic looks like, what disabled looks like and if you don't fit that mould then there’s a sense of surprise’. Not only is this damaging to the individual but for someone who maybe visually presents ‘a bit more autistic or disabled’, it's horrible being part of this stereotype that ppl put it in. and it’s not helpful for anybody. That’s what we really want to get across. You can't look disabled; you can't look autistic. There isn’t a defined look.

A spontaneous question, do you feel like sometimes ADHD, OCD and autism are used interchangeably as an adjective to describe how your personality or behaviour is? Do you feel that the tendency for some people to do that can really be damaging and just be another form of ableism?

Mia: Read an article about someone who experiences intrusive thoughts and was saying how awful it is at the moment that this trend of ‘letting my intrusive thoughts win’. Actual intrusive thoughts are things that if they are said out loud it could ruin someone's life. These aren't thoughts I want or thoughts that are conscious. It’s just like you were saying that it diminishes the person’s experience. Whilst obviously you can't police language, I do think awareness around using adjectives like this makes someone’s experience of having OCD or ADHD, it makes your quality of life not easy.

Jess: I would also say that maybe at the stage we’re at with our journey now is slightly different to where we were a few years ago. I think we are not so attached to such black and white ideas of ‘you are this but you aren’t that’. Whilst I think probably the way I experience the world sometimes as someone who considers themselves autistic is different to someone who isn't autistic. I also think that society really embraces the idea of understanding and compassion. Just because someone works in a way you don’t understand doesn't mean what they’re trying to do is necessarily invalid or have less of a value. We made a poster at one point, saying that ‘Not Everyone Is A Little Bit ADHD’. Labels aside, I just wish we could all be treated with the respect we deserve from everyone.

Based on what you’ve written about neurodivergent’s monotropic way of thinking, do you think this makes people in the community more self-aware? And if so do you have a personal anecdote of that?

Jess: phenomenal question. That’s something that feels very relevant to my experience. I would say ‘yes’ to answer your question of: do i think if it makes you more self-aware? I think the way I think is incredibly detailed in every sort of thing I think about, a plethora of details come to the surface. And honestly, its quite inconvenient a lot of the time. Even in terms of posting on social media, quite often, we were talking about the other day when writing the caption, that there are a lot of things that we feel that we would like to cover. Even just as people who are aware of their privilege in the community and how we’re so aware of those things and how they feel very important, so it feels difficult to summarise in short character counts. I think it means like I said earlier I find that intense a lot of the time.

You mentioned the social model vs medical model of disability. I felt there was a questioning of how we should perceive ourselves in society within the disabled community. If more people subscribed to the social model of disability, do you think this would reduce discrimination, stigma and/or prejudice towards people with disabilities? And would that enact better change for the community?

Jess: The questions are great! I think with complete certainty I think it would. When I think about government policy and statements that are given by people in positions of authority and influence, I think a lot of those things are exclusive and not very considered when it comes to the disabled community. I feel like embracing the social model would bridge that gap.

Mia: It's a little bit like the way we've modelled our training actually: is rather than it being around asking for accommodations, it’s around universal design. And actually, setting up these companies and these employees with the toolkit that allows them to cater to all.

employees. This isn't the case of some employees having to come to their employer and say: ‘help I can't work the way I need a to. We need help’.

Jess: It’s by default a little more flexible.

Mia: I think that’s the way forward. Workplaces should work for everybody.

Jess: Just to add onto that slightly. I think for a long time in roles that we used to be in, in workplace environments, we felt like maybe it might be unreasonable to ask for these things. But working together and doing things differently has taught us both, there are absolutely alternative ways of doing things that do work. Even the process of writing the book, I know HarperCollins have already explained that the process for them has taught them how to be more flexible and better cater for other authors who might experience things similar to the way we do.

Do you feel that because of your writing deal and having successfully published your do feel you’ve kinda prepared almost a stage for the next generation of neurodivergent writers in a not a pressured but more so gentle way of ‘due to the opportunities we’ve had and the accommodations we’ve had to make clear to people that we’re working with, we’ve made it maybe made it a little bit easier for those who may come later?

Mia: It's really lovely the way you put that because it’s absolutely the case. And the other day, when we did a talk, there were people at HarperCollins saying that we’ve started putting in systems in place to help lots of different writers but obviously neurodivergent writers. And I think even outside of the publishing world, its m thinking about going into universities, schools, workplaces and even people that we knew growing up sort of expressing how much it's changed them. It’s given us this real sense of ‘wow’ and I don't think we've processed that yet. And actually, we struggled so much to come and achieve what we have and i do think it has changed a lot of things, especially in our community.

Jess: It feels very self-indulgent. I think a lot of what we do is share our experiences of what we've learnt but also get closer to a quality. But we're very aware that it definitely doesn't involve just us. Nor do we want to constantly centre ourselves. Yeah, I really hope so. I'm very aware that there are people that won't be given this opportunity. As much as I detest that that’s a reality. I really hope that we can use our experiences to make their realities better too by being intentional and as aware as possible.

Mia: I think obviously it sucks that there are people that are more likely to get opportunities like this. But I do also think that to make real change, systemic change, it might take longer. There were several times when we thought: ‘I don't want to say this. I don't want to say that’. but actually no, sometimes you just have to throw yourself into it and hopefully amplify as many voices around you as you can at the same time. Like we said its grown into something bigger than us now

In your book, you also talk about the negatives of a capitalist society. How I interpreted it was how a capitalist negatively facilitates the difficulties faced by those with ADHD and/or autism. Could you tell me a type of society that you believe would be better in helping those with ADHD and/or autism fit in?

Jess: We've explored this topic a lot recently. I think we had a conversation with one journalist who said ‘oh, well, you know, a society that isn't capitalist wouldn't be great either.’ But I think we're allowed to partake in things whilst also critiquing them. And I think, whilst two people like us don't necessarily have the answer, it's really important to highlight the exploitation and discrimination often really exacerbates the people who are marginalised - i.e. disabled people and the people in our community who are otherwise marginalised as well. Capitalism exploits a lot of people essentially. There are some people who have the worse side of it.

Mia: And honestly, I wish I had a more clear-cut answer. The reason we talk about capitalist society, us among other people, is that we are oppressed by it, and we aren't able to function as those who benefit from it. As much as i’d love to say this works better, I think it shouldn't actually come on the shoulders of those struggling with that. But those in positions of power should be able to do that.

There has been an increase in awareness of ADHD and autism in the media, social media in particular. Is there anything that someone should be mindful of when navigating social media? Obviously, you both are influencers, so there might be a bias, but despite that, what do you feel as human beings, as individuals, think people should be mindful of?

Jess: It feels very weird for me to acknowledge us in that category. I felt like we've an interesting insight in the sense that we have a lot of ppl in our community who are influencers. And I would say, that, you know, without disrespecting anyone, not my vibe, I think there are a lot of people who reduce the ... for the sake of their own gain. That content isn’t as well thought out. When we began this journey, it was like ‘let's keep going and keep going’ And we even noticed ourselves in that cycle of burnout. We couldn't keep up with this constant need to be posting and feeding the algorithm and all of that.

Mia: It's funny because we got fired from our jobs beforehand but to begin with, we started to make a bit of money. For the first time we had a job we were managing that meant we could pay bills. Well, that's amazing but it was very easy to get sucked into the fact that we were making money and not feeling bad about ourselves.

Jess: It comes at a cost doesn't it. I think our physical and mental health really took a hit from that.

Mia: I think that’s the thing we say about these campaigners and content creators: it's great the work that they are doing. But because the conversation has grown so much, l see there's a huge market, it's disgusting to describe it like that. You get these content creators who are posting on multiple channels daily or twice a day, that probably have teams behind them that you don't see. We've spoken about this before. For young generations it’s damaging to see this and think I can expect that level of fame without knowing the reality of what it takes to produce content to that scale. Just because you see an autistic creator making money, but the reality is its probably right time and right place, background of being able to invest their money into a team and they’re not doing it all by themselves.

Jess: There's a level of privilege there as well.

Mia: I think that's one thing we worry about quite a lot. Are people thinking that they can achieve that?

Jess: We don't want to contribute to that.

Mia: It's not that easy and not that pretty.

Follow up question to this, based on what you've said, Mia, do you feel that due to the mass consumption of social media, there’s this sense of quantity over quality when it comes to content on social media?

Mia: Do you know why it’s so funny? When we first started, I do think there was limited availability to all this information. It’s brilliant that people are talking about it now. But it does become a bit of a ‘What do I listen to? What do I not? What's just trying to grab my attention? What is actually useful information?

Jess: Who's trying to just get you to follow them? Who's trying to buy their products? Mia: We've had quite a few coaches follow us, whose contents is centred around ‘10 reasons why you probably have ADHD’. This content I do feel like is quite damaging.

Jess: I think sometimes it can often be because people are trying to sell you a course or become a coach. And again, we’ve done sponsored content before and it’s one thing we’ve always been selective about, who we say yes to.

Mia: And even when we do take on sponsored content, we’re very open about the fact: ‘we’ve taken this on as sponsored content because we as creators need to pay ourselves. Please support us. It’s not like...

Jess: ‘You should buy this thing because it’s the best thing ever’ I think again the whole capitalism being intertwined with this. Pretty damaging.

Mia: It's a difficult thing to navigate. I don't think anyone is doing it on purpose. The tricky thing is especially as neurodivergent people if you can't cope in a traditional workplace, and you go self-employed you need to make money. But it does mean that it muddies the water for people looking for actual support whereas maybe falling in the trap paying for things that wouldn't solve the actual issues.

In terms of chapter 6: ‘To Mask Or Not To Mask Themselves’, do you have any advice for someone who wants to learn how to embrace themselves and be able to express themselves if they’ve been masking for quite a considerable amount of time or a short

period of time? And from your own personal experience helped you to reduce your masking?

Jess: I think there are positives and negatives to unmasking. I feel that I always need to say this when I’m talking about masking because we're very aware of that again when we're having this conversation, that we’re not just telling people to do that because sometimes masking does keep people safe. And again, we actually went to a protest last year for someone in Sweden called Emmanuel Fru, a black autistic man. He was detained for having an autistic meltdown in a shopping mall. And the way he’s been treated since whereby he was cut off from contacting his family and humiliated honestly. Basically, we don't want to say ‘stop masking’ because I think being autistic in a certain environment, especially depending on your identity outside of being neurodivergent, can be really dangerous. It can be like Emmanuel put you in situations that you absolutely should not be in.

Mia: It might make it an inconvenience to the individual and make them uncomfortable and the difference between life.

Jess: Basically, I think we’re keen to lean into who they really are whilst being conscious of the negatives that do come with unmasking.

Mia: It’s just not being ignorant to the fact that masking is different for everyone.

What’s your favourite thing to do to decompress and take a break? Do you have a preferred fidget toy or object that you like to use? Or a particular activity that you like to do?

Jess: Being aware of my sensory environment, you know. Having bright coloured lights on. I find that really relaxing. Honestly, I just think about being firm on my boundaries and not forcing myself to do things that I know that I can't manage. I think just essentially respecting my energy levels a lot more and just taking time in my own company.

Mia: For me it is the complete opposite. I'm basically like ‘walk, walk, walk’. I feel like I've always been quite energetic and active. It's one of the reasons I've moved to the beach. For me, sitting in a room, I’m much better at it now, sort of calm myself. For me to get out of my head, and sort of decompress, it is just going for a walk with massive headphones on so that the world can't interrupt my space. But, yeah, I think there's been days where I've said to you [Jess] that I’ve walked 40 miles, which is kinda ridiculous but therapeutic.

What makes you a safe person to each other?

Jess: I think, honestly, we know each other so well, we work in pretty similar ways. There’s

such a huge amount of love and respect there.

Mia: No need for masking whatsoever. It’s like some of the things we will say to each other. We couldn't get away with saying that to anybody else. Yeah, I think it's not a safety we've had with anybody else. I think just that not having to spend extra energy on communicating, especially verbally communicating. It's just like ‘text me’ even if we're in the same room. I think there’s a lot of understanding and empathy there I think, isn’t there.

Jess: I think so. And I don't want to push you into doing anything that will mean you will need to expend energy that you don't need to. There are never really expectations.

Mia: And even in the way we know that we're different for example, this evening I'm probably going out for a walk, but I know Jess will want to go back to her hotel room. For some people, they might question that, it might be like ‘oh no why aren’t we hanging out? Why aren’t we going out and doing things together?’ But the reality is we work differently, and we’ll see each other later.

0 Comments