Hi Alexandros! Tell us about your involvement with Writing East Midland's 'Write Here: Sanctuary' refugee and asylum seeker creative writing project

Write Here: Sanctuary is a writing residency project created by Writing East Midlands in partnership with City of Sanctuary, which offers a safe place for recently arrived groups from Eastern Europe, South Asia, the Middle East and North and sub Saharan Africa to express themselves through writing.

In 2016, Writing East Midlands offered me an assistant writer job for 12 workshops that would take place once a week at Leicester City of Sanctuary’s drop-in centre. Once I knew I had the job, I began going to the drop-in to get to know the refugees. So for about two months I went there every Wednesday when the drop-in was open, and just chatted with the people and we drank coffee and had lunch and by the time the project started the refugees and I more or less knew each other.

In 2016, Writing East Midlands offered me an assistant writer job for 12 workshops that would take place once a week at Leicester City of Sanctuary’s drop-in centre. Once I knew I had the job, I began going to the drop-in to get to know the refugees. So for about two months I went there every Wednesday when the drop-in was open, and just chatted with the people and we drank coffee and had lunch and by the time the project started the refugees and I more or less knew each other.

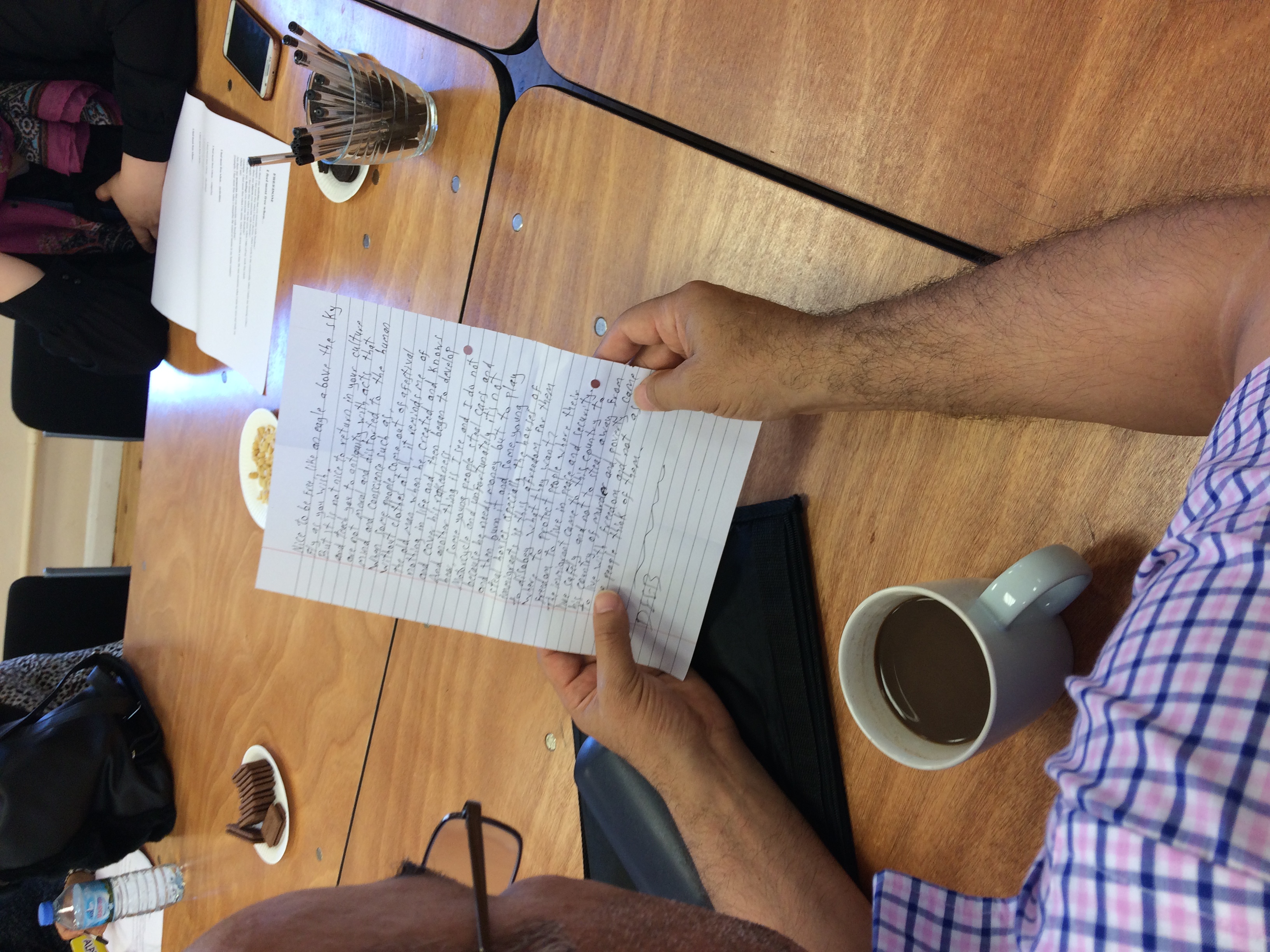

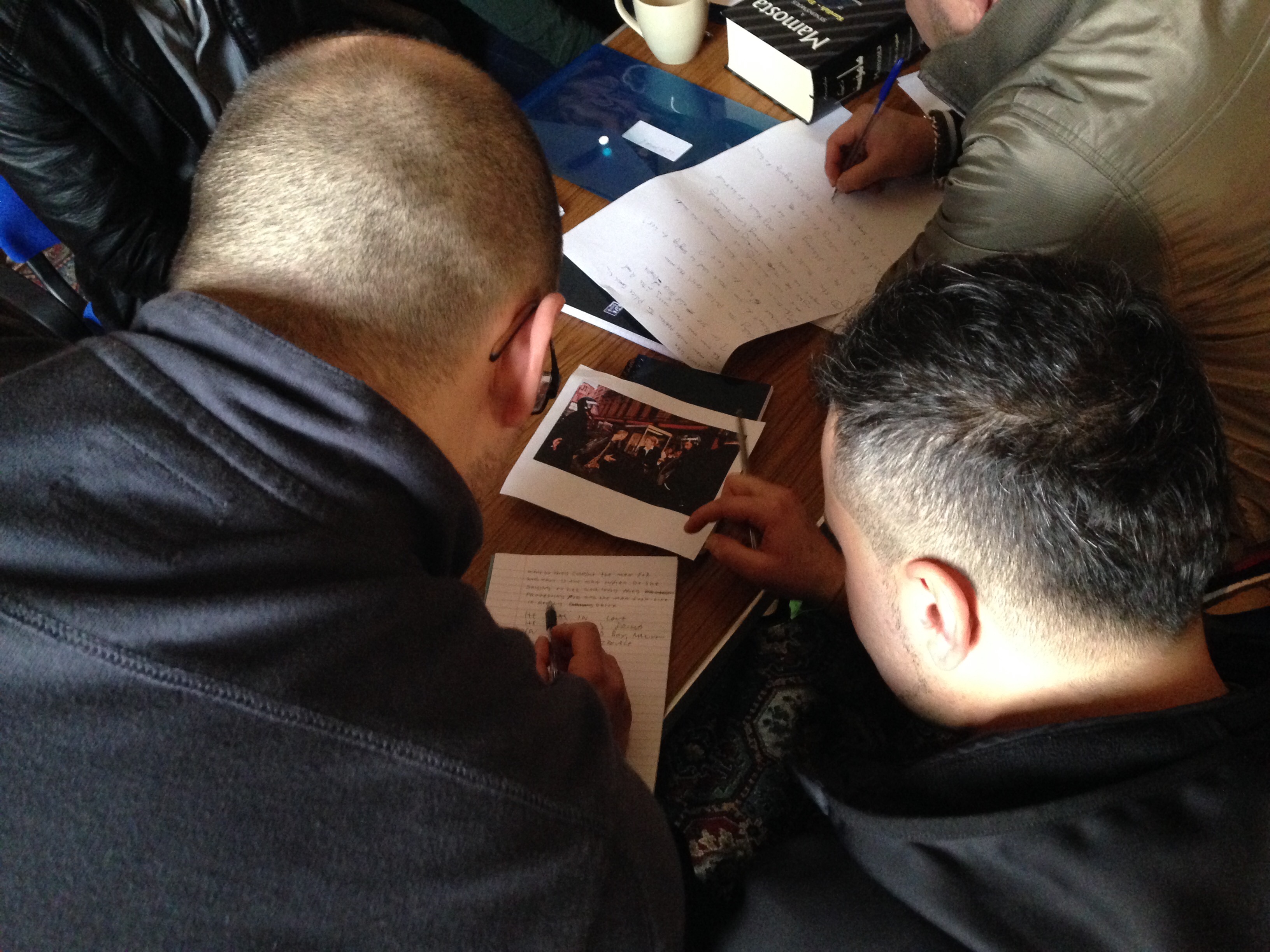

They didn’t understand the words ‘creative writing’ but that’s exactly what they did in those workshops, they wrote, and what came out were poems and stories. People who hardly knew how to write five words in English, kept on coming to the workshops, and slowly they taught themselves a few more words and then they put these words into the order they liked and something was created. There were others whose English was better and they wrote and wrote and wrote. People from different countries that didn’t speak with each other at the drop-in before exchanged phone numbers, they visited each others’ houses and talked about their happiness and their miseries.

Most of these friendships that were formed then, two years ago, still stand. For some of them, the workshops were the sole reason they came out of their houses, they were looking forward to them, it gave them something to do. Their lives are difficult and depression is always there. And I became friends with all of them, if not friends, then at least I’m on good terms with them, and we saw each other outside the drop-in. As a group, we appeared at various open mic events in Leicester, we went to the university, we had dinner in a restaurant, went to festivals in Derby and Nottingham. And they stood in front of people, even those ones who could hardly write, my friends stood up and read their writing and I sat back in a corner admiring them.

After those 12 workshops finished, I kept my Wednesdays off so I could be with the refugees at the drop-in. I got to know them even better and I became a volunteer at City of Sanctuary. We worked together on other projects, not related to writing, we went gardening, we created our own radio shows, visited Yarl’s Wood, and many, many other things. I became more involved in their lives, as a person - I mean that I wasn’t representing an organisation. I got to know about the destitutes, the G4S that wouldn’t fix their boilers for months and months, I saw the rats in their houses, I saw them becoming homeless, I met the great people who work for the Red Cross, I found out about the Loughborough sign-in centre where they have to go hoping not to be arrested without explanations, but some of them were arrested and I didn’t see them again, you know, the madness of the Home Office. Anyway.

Can you give us the typical outline of your day?

Having prepared for the workshop on the weekends, on Wednesdays I went first to town to buy biscuits and crisps and I was at the drop-in at about 10 am, where I had coffee and just hung around. Then, I set up the classroom, moving tables and chairs, making pots of coffee and tea for the participants, arranging plates of biscuits and nuts on the tables, sorting out their writing folders. Small things that I felt would create more of a homely feeling. The workshops started from 12.30 to 2 pm, but if you work with refugees you’ll find out that being late is the tradition. So, sometimes I would be late myself, just to take them by surprise. The participants were free to come and go whenever they wanted – they have lots of appointments: GP, Red Cross, solicitors, English classes, etc. Or they were free to come and go just because they felt like it, you know, why stop them? Creative writing is about freedom. I encouraged them to do as they liked.

Later in the day, usually in the evenings when I was back home, I would send these photos to them individually on WhatsApp. After a few weeks I found out that these photos meant a lot to them: some would share them with their families back in the countries where they came from, they had something to show to them. And the loners had something to look at and remind them of their day, and they knew that someone was thinking about them.

What ’s great about your job?

Tell us a bit about how the Journeys festival went at end of August

The Journeys Festival International is, as is described in their brochure, an annual festival that showcases the work of artists from the refugee and asylum seeker community. What I did for the festival was first to develop their Roots Group – a small group of local refugees who guide the company in creating the festival. I also tried to engage the local refugee community with the festival as the refugees with their chaotic lives, their depressions, and, usually, their limited English, don’t know about cultural events taking place in the city. There are lots of great refugee artists who live in Leicester. I tried to involve them at the festival and we showcased their work.

The festival itself was a soft sweet whisper that echoed around the city’s busy streets and its buildings: ‘we are here, we are the artists and this is our work, the work of the people that you call “refugees”’. But labels aside, for ten days there was music, dancing, films, theatre, art workshops, dotted throughout the city, in big central and small neighbourhood venues, all free, as free as the Moroccan tea and Turkish coffee my Syrian friends served: thank you Maya, Rawaa, Sara, and Bashar – nice tea, bismillah.

What were the challenges you faced in the role?

What are the highlights of your career to date?

I don’t have a career. I’m not saying it’s bad to have a career, but I don’t have one. The highlights of my time with the refugees so far are them opening the doors of their home to me, us sharing food from the same plate, getting to know their kids and becoming friends with them too. Or, now that I have moved to Loughborough, being offered a place to sleep in their homes when I visit them in Leicester.

How did you get into your line of work?

Mainly through not fitting in. When I was living in Greece my friends there were Egyptian immigrants who worked as fishermen, and the people I felt comfortable with were some beggars and some prostitutes I got to know at the 24/7 café I was working at. Growing up in Greece I learned the manners of the mainstream locals and I despised them, I realised I didn’t belong there and I kept myself outside of their circles and that’s why I entered the margins.

When I came to England I wrote about the people that I found beautiful back in Greece, the Egyptian fishermen and the others that I mentioned. In England, I studied social anthropology and creative writing and I tried many jobs, but either I wasn’t good enough or I got bored or the managers didn’t like me enough – anyway, something didn’t click there. And I didn’t enter academia as I couldn’t even get shortlisted for an interview, though I had a Ph.D. and lots of publications. And the sweet years passed by and I realised that I wasn’t made for a 9-5 job, and one day I saw an ad asking for an assistant writer to work with refugees, the Write Here: Sanctuary project. I saw possibilities in that ad, a little light. I applied for it and I got it because of my experience with the people from marginalised communities I told of you earlier.

The assistant writer job led to a lead writer job that led to my work with the refugee festival, and everything together led to the job I have now in Loughborough, where I live in the same house with young unaccompanied asylum seekers. But of course I didn’t just work with the refugees, I spent hours and hours and months and years just being with them, and when you hang out with people in a normal, everyday way, you learn a lot about them.

The assistant writer job led to a lead writer job that led to my work with the refugee festival, and everything together led to the job I have now in Loughborough, where I live in the same house with young unaccompanied asylum seekers. But of course I didn’t just work with the refugees, I spent hours and hours and months and years just being with them, and when you hang out with people in a normal, everyday way, you learn a lot about them.

It was because of that first writing project that I began my journey into the lives of refugees and asylum seekers and a big thank you goes to Aimee Wilkinson and Henderson Mullin from Writing East Midlands who believed in me.

What interested you about working creatively with refugees?

I like working and being with people that others tend to look down upon. I’m good at that. I put labels on people, as most of us do, I do it usually without realising. I think the beggars, the prostitutes, the drug addicts, the refugees, the middle class, the Muslims, the Christians, and so on. Then I like breaking my own stereotypes and discovering the hidden beauty. I say hidden, but I mean that we keep our eyes away from them and we don’t see, we just judge because this is what we were taught to do. If you ask me to work with drug or alcohol addicts my first reaction would be that of fear, I would feel scared. But I know that that’s because I don’t know them, and I do know that if I get to know them I will peel out the label and see the human.

So for me, at the moment, it happens to be refugees that I work with. I also happen to work creatively with them because I have this Ph.D. in Creative Writing with a background in ethnography, and all those factors work well together.

You ’ve been granted the ability to send a message to 14-year-old you. What do you say?

‘Read Aeolia by Elias Venezis.’ I wouldn’t say more than that because my 14-year-old self would get bored with a lecture.

Do you have any advice for young people interested in doing your kind of work?

Go towards the refugees with your eyes open and with compassion at the core of your heart. Everything else will follow.

About Alexandros

Alexandros Plasatis is an immigrant ethnographer who writes fiction in English, his second language. His work has appeared in American, Canadian, UK, and Indian magazines and anthologies. His writing is represented by the American literary agent Pamela Malpas. He works and lives with refugees in Loughborough.

Read more

We caught up with Aimee Wilkinson, Head of Artistic Development at Writing East Midlands.

0 Comments