Could you please introduce yourself to the reader?

Hi, I’m Sarah. I’m British (and French too since Brexit), I did my first degree at Lancaster University, then moved to France where I did my PhD at the Université Sorbonne Nouvelle, where I’m now a professor and specialise in young people's political participation - both electoral and nonelectoral.

Your academic work focuses on how young people engage politically, whether through voting, protest or other means. What drew you to this area of study?

I was interested in politics from a very young age due to my family background and school teachers. Margaret Thatcher was prime minister when was I was at secondary school and university. My PhD was about youth culture and youth policy in the 1950s and 1960s. I then started working on contemporary youth policy and youth politics. It made me realise that everything interacts - youth culture, youth politics, youth protest and the youth policies that politicians develop (or not) and whether they try to attract young voters. So taking a holistic approach is helpful - analysing things in the round and the relationships between them. For example, to comprehend young people’s protest actions, you need to take into account policing legislation introduced by the government, and the impact of voter ID on young people’s voting.

I don’t think we’ve ever talked so much about young people’s participation in the media and academia. Many media narratives are negative and some research does not acknowledge young people’s lives as a whole and just focus on specific aspects. But everything is related. I’m very much an advocate of adopting a holistic viewpoint, which takes into account multiple factors, and that’s the approach I try to use and promote in my research. A young person’s involvement in the electoral process depends on many different things. Plus a young person can volunteer, protest and vote.

Your book ‘Politics, Protest and Young People: Political Participation and Dissent in 21st Century Britain’ was published in 2019. Do you think the youth vote landscape has changed? If so, why?

My book was published two years after the 2017 general election which saw a significant rise in young people’s interest and engagement in politics. Notably, the turnout rate went up among young women and youth from disadvantaged backgrounds. This was mostly due to the Labour Party leader Jeremy Corbyn - remember Corbynmania - who was hugely popular with young people. The Labour Party also devised a youth manifesto which contained a range of policy commitments that were really popular among young people and promoted this through youth-friendly communication. Corbyn galvanised a lot of support as a figurehead and reached out to segments of young people who didn’t normally vote. There is a definite parallel with Bernie Saunders in the United States. Just two years later came the December 2019 general election with the Labour Party using similar strategies.

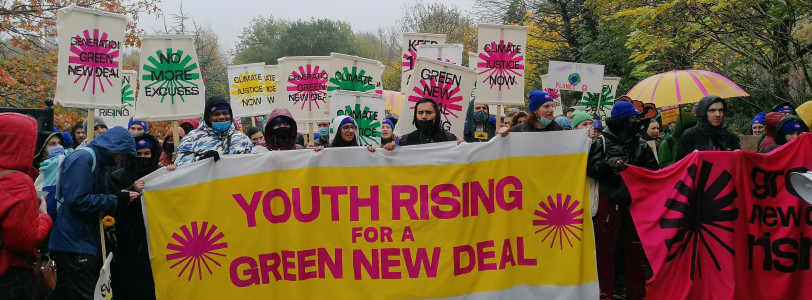

However, what happened in between those two votes has been crucial to young people’s political participation. As we all know, over 5 years ago now, in August 2018, Greta Thunberg started her climate strikes that led to Fridays For Future, and soon after Extinction Rebellion (XR) was launched in Britain. Along with other new movements, they have succeeded in drawing media, public and political attention to the climate crisis.

Young people have been mobilised in various ways (not just direct action) about climate and environmental issues, as well as issues that tend to be associated with values and identity of particular concern to young people especially. I have observed a shift away from support for whole political programmes, while a range of advocacy and protest movements have garnered support and action from young people in particular like never before. It’s a significant change in non-electoral political participation.

Young people are often labelled ‘apathetic’ or ‘disillusioned’ in their engagement with electoral forms of participation. What do you think has led to these labels historically, other than low turnouts for the 18-24 age group?

The labels come from two different places. Within academia, ‘apathetic youth’ was a term used for many years by researchers not specialising in youth participation, where the blame was placed on young people themselves having lower electoral turnout rates. It was implied or interpreted that they were lazy, self-centred and narcissistic, for example. Once one of those handy narratives gets going, it tends to be re-used and replicated without critical distance or analysis. Those labels are then picked up by the mainstream media. The media has used generational criticisms of young people for decades. It’s disseminated and replicated by ordinary people. Hence huge generational negative stereotypes about young people (and not just about voting).

However, in the 2001 general election, turnout of young people was the lowest it had (and has) ever been (in fact turnout also dropped for all age groups in this election). This fall triggered scientific interest in young people’s electoral behaviour in particular. Since then, youth politics specialists have developed explanations that focus on the notion that most young people are not disinterested in politics, it’s that most politicians deliberately do nothing to attract young people into politics, whether through policies or communication, etc. This can be because young people tend to have lower turnout rates, so it is more ‘cost-effective’ to target older segments of the population in an ageing society. Recent research has shifted the onus from young people being politically apathetic to politicians failing to provide youth-friendly policies and politicians, i.e; young people are alienated by politicians.

In your book you argue that there has been a ‘lack of understanding of the many ways young people are participating politically.’ What has led to this lack of understanding and what can we do to combat this to gain a more comprehensive picture of young people’s political participation?

Traditional definitions of political participation initially focussed on electoral participation. Of course that evolved after the 1960s when there were more protests. There is no one definition of political participation. Conventional and non-conventional politics don’t make sense to me as a means of categorising political participation. It’s a way of demeaning non-electoral forms of participation (and thus young people’s engagement in these, and so young people themselves). It’s saying that the only ‘proper’ way to participate is in elections is by voting once in a while.

In terms of predicting how and whether young people are going to vote in future elections, we have to be really careful about sampling size. The British Election Study sample less than 100 young people and then extrapolates it to generalise about young people. The sample size is tiny and doesn't account for university towns. This is then reproduced in the media.

I contend in my book that young people are making many decisions everyday that are political. For example, consumer choices of whether avoid certain brands and outlets, or to deliberately buy second-hand products, or not purchase at all. The choice to try to influence older family members or not. Whether you take a bus, or complain that there isn’t a bus. Everything is political. Of course, not all young people have the agency to make such choices, or conceive these choices as political. It depends on the intention or interpretation.

What is ‘do-it-ourselves’ politics and why do you think it is a recent trend?

The term evolved for me after my interviews with young people going back over a decade. Something that really became obvious to me was one commonality running between groups of people that varied vastly in terms of age, background and interests. All these young people felt the need to do something, be involved and act. To not just be a passive bystander because they think elections aren’t enough or they aren’t old enough to vote. For all of them, carrying out actions - to do something - has been important, as is the conception that power-holders aren’t doing enough. So that explains the doing, but doing something together - with other like-minded people - is also important, hence the ‘ourselves’ in DIO politics.

The ‘ourselves’ part of the term comes from his sense of togetherness. Being part of a group, community or movement grants a feeling of togetherness which counteracts the negative emotions of feeling powerless. It brings hope and solidarity. ‘Ourselves’ also means us as opposed to them.

The ‘doing’ can be individual actions. Nonetheless, you’re always part of a bigger group or critical mass. It may come from a place of frustration or anger. You’re more likely to act if you’re around peers who are also heading in the same direction. People going into higher education are more likely to vote, go on protest and engage in ‘do-it-ourselves’ politics. Growing levels of young people are going into higher education so there is an increase in political participation.

DIO politics and the existential need to do something has been really prominent in the dozens of interviews I have conducted with often very emotional young climate and environmental activists in FFF, XR, Just Stop Oil, GJN, etc., as well as the positive emotional outcomes from doing something within a collective.

If you just look at elections or just protests or just civil disobedience, you won’t understand the full picture. Do-it-ourselves politics helps to give language to broader political participation - and it fits with the holistic approach.

What do you think motivates young people to vote in general elections?

The issues that are important to young people are often very similar to other generations. When we think about what encourages young people to vote, we have to think about leaders, communication and policies. If we look back to 2019 and why the Labour Party got so many young people voting for it, Jeremy Corbyn was specifically reaching out to young people and influencers. It was more like peer-to-peer communication, as well as a specific policy programme that targeted young people.

We know that older people tend to vote more and they tend to vote Conservative more, hence why the Conservative Party has focussed more on older rather than younger people. The support for the Conservative Party among young people has really plummeted, over the last couple of years - it has decreased since 2019 when around 20% of 18-24-year-olds voted for Tory candidates.

2019 seems a long time ago now and so much has changed since then. Life continues to be difficult for young people living in the cost-of-living crisis. Also, this is the first generation since the mid-20th century whose living conditions have worsened and for whom social mobility has fallen. The social ladder is much more difficult to climb. Conditions are worse for young people now than it was for their parents. The transition to autonomous living is longer and more difficult. The circumstances are worse than they were in 2019, particularly with the ongoing impact of austerity and of course COVID-19. Living conditions and quality of life for young people are worse than they were in 2019.

At the moment, prospects don’t look rosy. Moreover, political leaders have changed. Starmer is not perceived to be as authentic or appealing as Corbyn, and the Labour Party’s policies are not apparent yet. I think a big problem in the UK is the electoral system which makes it very difficult for candidates from smaller parties to attract votes, for example, the Green Party would likely do well with young people in a proportional representation electoral system.

What is your encouragement to young people that youth voice matters?

The youth voice matters for young generations themselves and for older generations. Political parties tend not to let in young people or to give any form of power or influence (for example, in youth wings or in policy development) for fear of disrupting the established order and power dynamics, or losing older voters.

However, it is important that young people can express their values, priorities and hopes, and that their voices are heard. It is often said that young people are the future, but young people are the present too and politicians have a responsibility to pass down a better future. Without young voice’s engaged in climate and environmental activism in recent years, I’m convinced we wouldn’t be talking about the climate crisis in the same way. Young people certainly raise awareness and have a certain degree of impact on policies. It’s important at a time that is so difficult for most young generation for them to feel part of something positive, to recognise positive change, and to acknowledge things can change

It’s certainly not for me to tell young people what they should be doing or not doing or how they should be doing it. What I do know is that whether through volunteering or campaigning, being part of a group or collective (online or offline) helps with feelings of agency, belonging, hope and solidarity. This doesn’t mean that all associations are welcoming to everybody, so it might mean taking time to find your tribe. Importantly, feeling anxious alone and helpless can be helped by trying to take action on whatever scale because it provides a sense of togetherness, solidarity and hope critical for bringing about positive change.

0 Comments