Can you please introduce yourself to readers?

I am: a black woman, a feminist, a daughter, a mother, an activist and a British textile artist. The particularity of who I am informs the projects I work on.

I am currently based in in Hastings, on the east coast of the UK. But before that I lived and worked for about 10 years in southern France In fact I have lived in Europe, (Italy and France) during several periods of my career. I also had the opportunity to live and work in Southern California in the 1980s when myself, my husband and our new born daughter moved to Laguna Beach.

How did your artistic career start?

I was born in London to African Caribbean parents recently arrived from Trinidad and St Vincent. When I was 10 years old, We moved from what was then a black and Irish community in Notting Hill gate to a small village in Hampshire.

By luck and the kindness of strangers, at 14 years old I started Saturday morning classes at Farnham School of Art and eventually after a year at Berkshire School of Art and a foundation course. I ended up at Central St Martin’s School of Art.

It was a very particular time of free education and grants, which meant I was privileged to be part of a really diverse group of students. Many came from working class families and were often the first to pursue further education. It was an environment where anybody, with the right skills, could get into these institutions. Within the art schools at that time, there was a commitment and excitement about democratic institutions. For example, student representatives sat in on the hiring of new professors and teachers.

I initially studied fashion and Textiles and was able to experiment with different materials with no cost implications. My heart breaks sometimes when I see how much money and the hoops and obstacles young people have to jump through trying to study art today.

What was also wonderful (and made a huge difference) was the amount of employment around. After graduating, I worked for about fifteen years as a commercial textiles designer. My first job was in Italy where I had the chance to work with a great knitwear designer called John Ashpool. I think he had trained as a painter and his approach to the work was playful and experimental. I now see how it has informed my subsequent practice.

You’ve worked in fashion and textiles. What drew you to felting initially and how do you approach the medium now?

I started felting really by accident, or rather, for fun. I had been creating knitted ‘art to wear’ on domestic knitting machines and unexpectedly hurt my back. For several weeks it was too painful to sit and knit so, always wanting to use my hands, I started experimenting with other crafts. I got into making papier-mâché vessels which I loved but the methods of applying natural Gesso and sanding in a small space became problematic.

So I started experimenting with Felt making and got interested in Nuno felting. The key thing to know about nuno felting is that you’re passing fibres through fabric, usually silk. When you’re making felt, you're just irritating the fibres. With nuno felt you’re using that same friction but passing fibres through fabric. I got very skilled at using nuno felting to make scarves, often working with Merino wool.

Later at a craft fair where I was selling nuno felted and stitched scarves someone approached me and told me about ‘The Shape of Things to Come’, an Arts Council England bursary to encourage more visibility of a diverse range of makers.

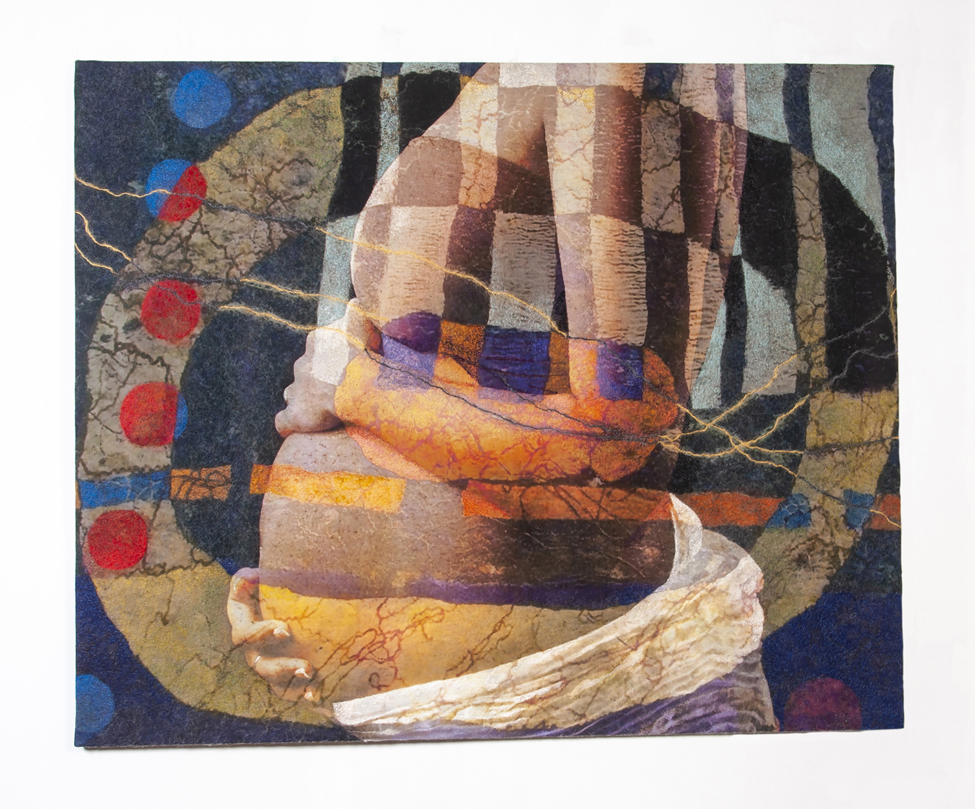

This bursary was an opportunity to develop some ideas I had for an autobiographical piece. I found some old pictures of my mother’s wedding day to my stepfather when I was about four years old. I wanted to see what would happen working with the Nuno technique on a larger scale if I enlarged an image, printed it on silk and felted it. I decided to only stitch the parts of the image that I remembered: my blue dress, my mother’s corsage and the texture of her dress.

I presented the piece for the bursary application, won an award and part of the prize was a one-woman show at Leicester Museum. It was incredible to have a team of people help you mount an exhibition. I was very ambitious, trying different things. I spent about two years creating some very large and personal pieces, all based around the original wedding day photo. The exhibition was called Negotiations: Black in a white majority culture.

It included many large felted portraits and it was the first time I ever made a lenticular! A lenticular structure gives images an illusion of depth or motion when viewed from different angles.

While researching images for the show I had discovered that while my mother, a black woman, was marrying my step father, a white man, just a few miles away in Trafalgar Square, there was a ‘Keep Britain White’ demonstration. I couldn't help thinking about that juxtaposition. So, I made a lenticular with the wedding day on one side and the demonstration on the other. It was a powerful large piece and was well received.

Can you give us an example of how audiences respond to your work?

In that same Leicester Museum exhibition, I had one piece called Enid with a montage of Enid Blytons’s children’s book The Three Little Golliwogs and I included an actual Golliwog badge. There was a period when, if you bought Robertson’s jams and saved the label, they would send you a rather beautifully made enamel Golliwog badge. ‘Enid’ was about how confusing those early messages for black children at that time.

The night before the opening I met one of the guards at the Leicester Museum. She was a white, Irish woman. She told me how touching she’d found the Golliwog piece. She told me her story about being ostracised in her school and made to feel ‘other’ and how by making friends with other marginalised black children she was also targeted by racism.

When the show opened other white people sort me out to tell me their stories and apologising saying that they’d no idea about the racist messages behind the Golliwog badge.

What role do your various identities such as being a Black woman, activist, feminist and British play in determining your medium and work?

All my work is entirely formed by my identity. There was a lovely quote I found on Instagram which defined an activist as someone not driven by fame or money but someone who is compelled to act. In a way, since 2008, all my work has grown from a response. I respond to an event or situation which sticks with me. I then get very angry and frustrated. I then start to get creative ideas.

For example, my 5 Times More series. I was in my studio listening to Woman’s Hour. They discussed a new report which revealed that black women are five times more likely to die in childbirth than white women. I relistened to it and couldn’t quite believe it. It was a government sponsored report and I found it online. The report was full of extraordinary inequalities. Black women are 120% more likely to have stillbirths than white women. I knew I wanted to make a project around motherhood and childbirth.

My process usually entails looking for stock images, collaging them on my computer, I then print them on fabric and felt them. Once I find the image, it then becomes entirely about my technical process. The work is always driven from a particular story of form a level of disbelief.

Tell us about your recent work, Waste Colonialism.

Fifteen years ago, I was in Uganda and we set up a charity to help AIDS orphans out in the bush. One of the things that struck me as I visited each year was not just the growing waste but also how well-dressed everyone was in Western clothes. In the bush, an hour away from civilizations, people would be wearing clothes from Laura Ashley or New Look.

I was taken to Kampala Market, a particular second hands clothes, which is absolutely enormous. One tonne bales of clothes and textiles would be delivered every Sunday. Women would buy sections of the bale. One women would just specialise in children’s cardigans, one who just sells bras. In the markets, everyone has their section selling their category of clothes. On the other side of the market are men working on sewing machines where buyers could have their items altered. There was a wonderful economy.

Over the years, as we were visiting, there were more and more complaints about the quality of the work. People who were buying their section only to find that the quality wasn’t there and the place was in crisis. It was the impact of fast fashion. I had another moment of frustration and disbelief.

I was invited by Launa Hamilton Brown, aka the Banksy of Knitting, to contribute to an exhibition at Hastings Contemporary who wanted to showcase black artists. It was a show called Black Artists, all African or Caribbean, and we were given complete free range.

So, when I had this opportunity to exhibit at Hastings Contemporary, I worked on a large scale ambitious lenticular addressing fast fashion and the scale of the landfills. In Uganda, there are a lot of dumps that are burnt. In contrast, in Kenya and Ghana, there are beautiful mountains. I made a photographic collage of a mountain created from waste clothes. I also put together a collage of women in the Global North shopping, featuring brands like Shein, H&M and Zara. On the one side, you have happy women shopping. On the other side, you have the consequence.

To accompany the work I made a file of resources. We also delivered a series of workshops with a group called A-Dress who repurpose clothes and show them through catwalks. They focus on the conditions of people who create fast fashion items. Part of the time, with these issues, they feel so enormous. I’m a believer in starting small, communicating and connecting with other people. We’re only going to change things together.

What advice would you give someone who wants to use felt or craft to make a social or political statement?

Firstly, anger is important but it has to be productive. We can’t just share our distress. We need to activate and inspire. The advice I would give is to figure out how to get that anger out. One great way is to go on protests and physically let that anger out. You need clarity, because if you’re angry it’s very difficult to do good work. The beauty of craft is that it affects your breathing, your hand-eye coordination. If you’re angry, that won’t work. Anger is the motivation and the determination that produces the work. It’ll spur you on.

Secondly, find your art form. If you haven’t had formal training, just sign up for any free workshops. You will find your medium, you will find what gets you excited. It’s really important to find that exciting medium because that will excite your audience. What inspires you? What relaxes you? You might surprise yourself. Once you’ve found that, you’ve got your anger, determination and excitement to make projects that will excite others around you.

Thirdly, reach out and connect up. Instagram is fantastic for that. Connect with people doing similar things to you, or even people who are completely different but doing interesting things. Groups will come together and creative collaboration is the only way forward.

0 Comments