The Covid-19 pandemic has affected all aspects of our lives and has pushed the world further and further into the digital space.

As lockdowns ensued and social distancing was mandated by the government, schools were forced to move online. Not only were some schools and students unequipped to move into the world of Zoom and Microsoft Teams, but this unprecedented shift took a toll on students.

The Data

The 2021 State of the Nation research report conducted by the Department for Education looks at how the pandemic has affected children and young people’s health and wellbeing.

The report analyzes many aspects of health and wellbeing, not just limited to education, and ultimately suggests that “children and young people’s mental health and wellbeing had, on average, reduced during the pandemic, particularly during periods of school closures.”

It also noted that there was “strong evidence” that some groups, such as those from low socio-economic groups, were “disproportionately affected by disruptions to in-school teaching and wider pandemic controls.”

Disruptions to face-to-face learning because of the pandemic could be a key factor affecting university students’ happiness with their courses.

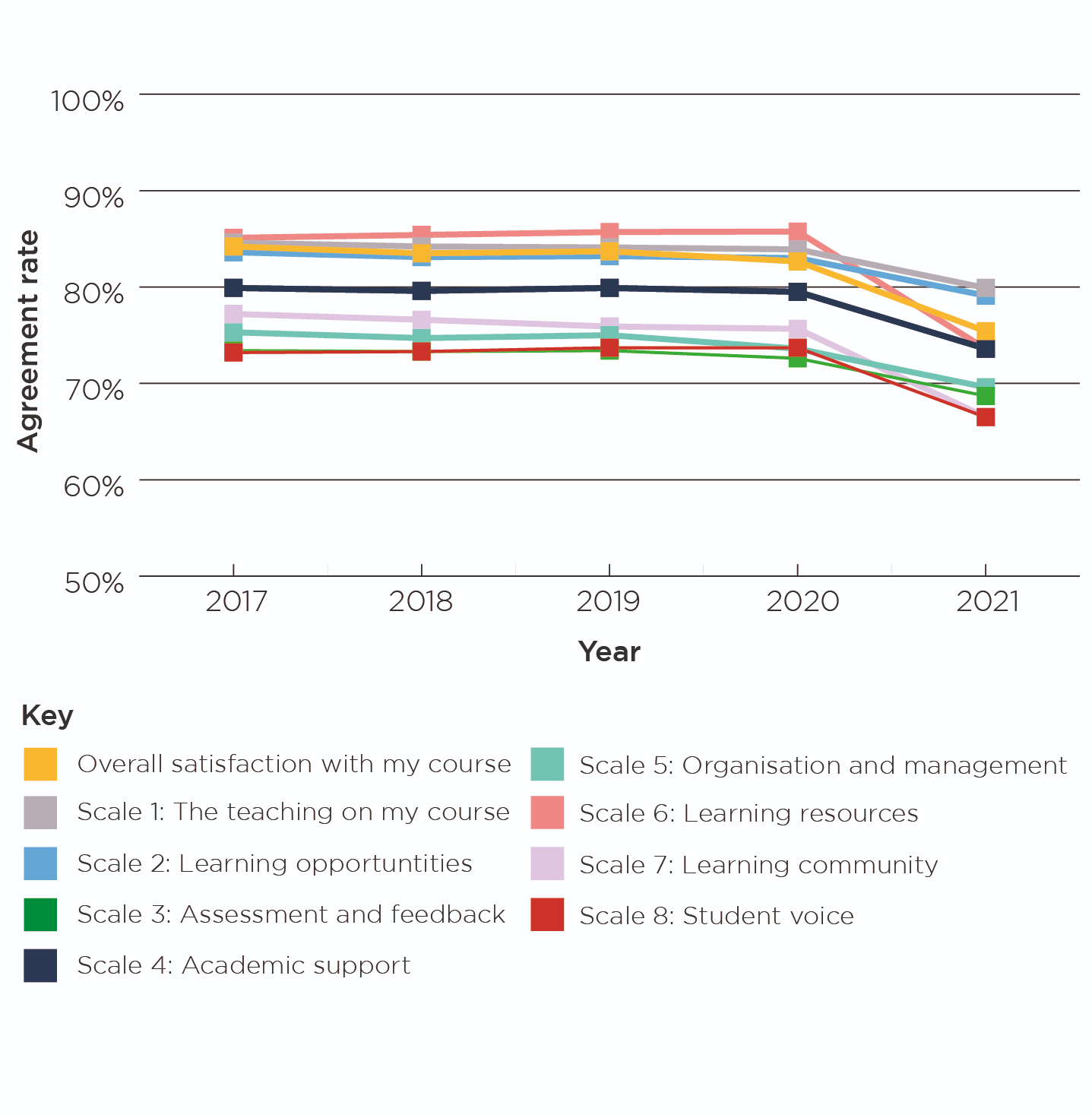

For example, the National Student Survey, an annual census of all final year undergraduate students at UK universities, saw a decrease in satisfaction with university courses during the pandemic. This is unusual, as satisfaction rates from previous years are usually consistent. Graph Credit: The National Student Survey

Graph Credit: The National Student Survey

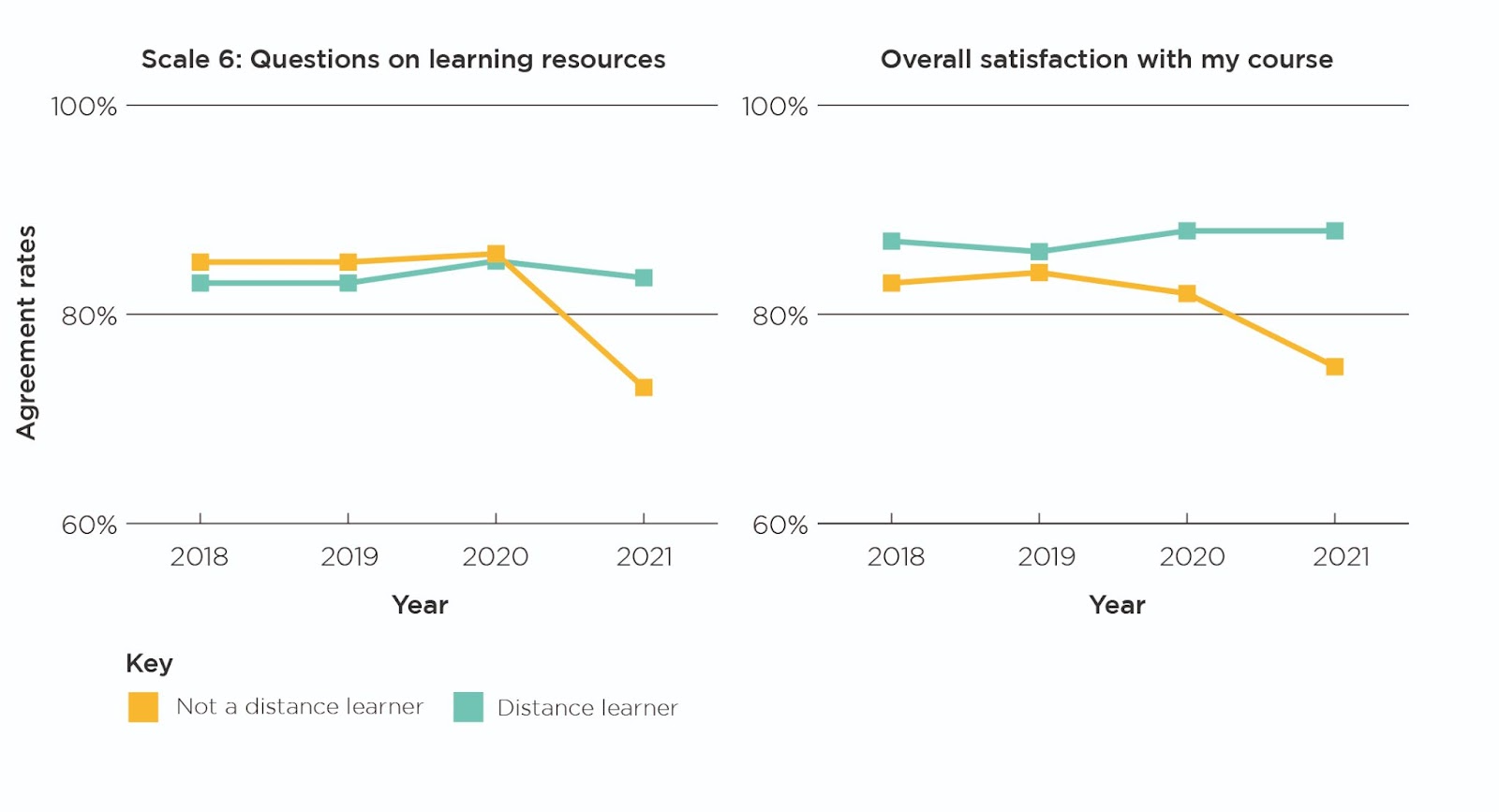

Between 2020 and 2021, course satisfaction for students who were already distance learners only decreased by 0.34 percent. However, course satisfaction for students who were forced into distance learning by the pandemic saw a greater decrease of 9.3 percent.

Only 47.6 % of students agreed with the statement “I am content with the delivery of learning and teaching of my course during the Covid-19 pandemic.” According to the report, this lack of agreement could suggest why the overall course satisfaction rate decreased.

Graph Credit: The National Student Survey

Graph Credit: The National Student Survey

The Office for National Statistics also saw similar results in its report “Coronavirus and higher education students: England, 24 May to 2 June 2021.”

61% of students enrolled in higher education before the start of the pandemic said the lack of face-to-face learning had “a major or moderate impact on the quality of their course.” 52% said the pandemic had “a major or significant impact on their academic performance.”

While the data from both the National Student Survey and The Office for National Statistics are of a high quality, it is important to note that the data does have its limitations. The National Student Survey noted that student responses were voluntary and that the Covid-related questions received a response rate of only 38.6 percent, mainly because the questions were asked only online. While the survey did take this into account and only published the “higher-level statistics,” the data may not be fully representative of the larger population because of voluntary response bias. Similarly, The Office for National Statistics reported the data had “a relatively small sample size and low response rate.”

The Students and Teachers

Alison McClintock, a lecturer at the University of Roehampton, taught her current cohort of students virtually during the pandemic. For her, there were some benefits to the shift, as digital capabilities meant she could have guest lecturers from further away without the need for them to commute to campus to speak. But despite this increased connectivity, teaching online was difficult for students and lecturers alike.

“Online learning hasn’t been easy for lecturers or students,” McClintock said. Digital capabilities allow us to bring people together, but there is also an element of just speaking to rectangles teaching into the void.”

One challenge with online learning was that some students were comfortable showing their faces while others weren’t. McClintock said that often students weren’t using their physical voices and were typing instead, and when they get used to the virtual environment they might not be as comfortable with talking and participating during in-person classes as Covid restrictions begin to ease.

Now McClintock and her students have returned to campus, which she welcomes as she is more able to read the room, notice when her students are understanding the course material and see their engagement levels. However, she also noted that students are still getting used to “business as usual” after being away from campus for so long.

“The students can be slightly tentative and need to feel some reassurance before they start a project,” McClintock said.

“They may need more time to think before they start, and I think a lot of universities are giving students this because of everything going on in the world right now.”

McClintock believes that hybrid ways of working is the way forward for universities because having access to online resources that can be replayed and accessed by students who may not be able to get to campus will benefit students. Using Zoom to give students access to speakers from other time zones without travel restrictions means we can broaden the uni experience and make sure students are enjoying learning.

Milie Porter is one of McClintock’s students, and she too has experienced the pros and cons of distance learning.

Porter is a third-year student at the University of Roehampton who transferred to the university after spending one year in person at Kingston where she was unhappy with her course.

Despite transferring during the pandemic and moving to a distance learning model, Porter is satisfied with the resources provided by the university and the delivery of her journalism courses. However, Porter noted that distance learning has made it more difficult for her to make the most out of her course because of difficulties with group work, limited access to on-campus facilities, obstacles faced when communicating solely online and even a lack of confidence in participating online when peers did not contribute either.

“The pandemic has made me question if I made the right decision [about attending university],” Porter said. “I have a slight regret of not working more to make more money before deciding what university course to pursue, and I have felt under more pressure completing tasks because I have had less interaction to ensure I am completing my tasks in the right way.”

Porter spent one year in person followed by an additional two years of mostly distance learning and said that her course has improved as Covid restrictions have lessened.

In comparison, Jessica McEwen, a first-year history student at Queen Mary University of London, has never known university life as anything other than a mostly online program. All of her lectures are pre-recorded and she only attends in-person seminars two days a week. As a result, McEwen does not feel as though her university experience or the effectiveness of her course have been negatively affected by the pandemic. Instead, she enjoys the flexibility that comes with being able to watch lectures on her own time and at her own pace.

“I am absolutely loving the content and topics I am learning as part of my degree, and this has not been affected by the pandemic.”

While McEwen is content with her university experience, she struggled when her high school first moved online during the height of the pandemic. The pandemic and the lockdowns mostly affected her Sixth Form experience, completing her A-Levels, and her preparation for her post-18 options.

“In my experience, in the first lockdown when schools closed, “online learning” was very independent with teachers uploading some resources online, but for the most part leaving it up to the students to teach themselves the content,” McEwen said. “However, when schools closed for a second time, I had access to and attended lessons online and the involvement of teachers felt much more significant. I enjoyed distant learning much more the second time around as I was actually being taught the content by my teachers.”

McEwen’s university program is scheduled to return to being completely in person during her second year. Unlike Mille Porter, who has experienced university online and in person, McEwen worries about adjusting to an in-person course after only being taught online.

“Sometimes the thought of being completely in-person makes me feel a little nervous because parts of my university will be the complete opposite to what I am experiencing at the moment, which may take some time to get used to,” McEwen said. “I am worried that I would wish for my lectures to go back online, which may not be a possibility.”

So what does this all mean?

As previously mentioned, the data is reliable and accurate but may not be entirely representative of the greater population. This is because, as response bias describes, those with strong opinions are more likely to volunteer their responses, which could be why we see such a dramatic change in course approval rates in the data. It is also important to note that different cohorts of students will likely have different views on the effects the pandemic had on their education, especially those in higher education. Older students, like the ones surveyed in The National Student Survey, may be more likely to be dissatisfied with online learning because they have experienced “college life” and know how different it is to in-person learning. However, younger students may be more satisfied with their courses, like Jessica McEwen, as they have less experience to compare distance learning to. In order to analyse the full and complete extent of the pandemic on education, there needs to be more comprehensive research to analyse, possibly over the next few years.

0 Comments