What is objectivity? It’s a term we always hear in regards to the media, but what actually does it mean? Merriam Webster defines it as “the lack of favoritism toward one side or another: freedom from bias.” In other words, to report news objectively is to recount the goings on of the world without a specific agenda to promote or a favourite politician to support. I suppose the next question is, where did objective news as a principle come from? For most of Western History, print publications (like pamphlets) were just another method of the King or landowner passing down whatever they wanted their subjects to know, or a method for the Church to communicate with the faithful. As the philosophies of the Enlightenment worked their way into all aspects of society in the 18th Century, things began to change, including news publications. Just as artists and scientists adopted the Enlightenment principle of reason to explore the world, untethered from God and the Aristocracy, so too did news publications, who sprang up to offer accounts of social and political affairs. This offered a new perspective on the role of objectivity in the Press, as the same Enlightenment principles that tried to understand the natural world without bias were being used to understand society.

British philosopher Terry Eagleton begins his book ‘The Function of Criticism’ with an account of the two earliest British newspapers: ‘The Spectator’ and ‘The Tatler’. According to Eagleton, both of these papers used “moral correction and satiric ridicule” to offer criticisms of the Aristocracy that would have previously gotten writers imprisoned. At first glance, this new freedom may have enabled an objective type of journalism that could inform regular citizens of current events, but, according to Eagleton, these publications were far from objective - largely serving the purpose of the emerging Bourgeoisie, while creating an acceptable way to offer criticisms of the ruling class.

What was even capable of being said, Eagleton notes, was defined by England’s ruling class. The very ability to participate in the ‘disinterested’ debate of English newspapers usually meant that one had to be a landowner too - ironically “only those with an interest can be disinterested.” The debate, disagreement, and coverage of these papers were all predicated on people who were impartially trying to grease the wheels of the society that kept them and their fellow landowners on top.

Where Eagleton was critical of the European Press for not being objective enough, Dutch Philosopher Søren Kierkegaard offered harsh criticism of Copenhagen’s Press for being too objective. Christian Existentialist Søren Kierkegaard debated in his verbosely titled ‘Concluding Scientific Postscript to the Philosophical Fragments’ whether rationality makes life meaningful. Most would argue that being able to reason makes our lives easier, but to Kierkegaard life should not be easier, but harder. Whereas his Hegalian contemporaries worshipped rationality in all areas of life (Hegelianism is summed up by the dictum that “the rational alone is real”, strikingly similar to René Descartes’ famous “I think therefore I am”, although Hegelianism is attributed to G.W.F. Hegel), Kierkegaard contended that reason is only of limited value. Yes, reason makes life more convenient, but it does not give us what we all want: a meaningful life.

To Kierkegaard, those who live solely by the dictates of reason are under the illusion that they are living a meaningful life, for nothing can define the reason of one’s life, not even reason. Or as Kierkegaard put it, “The crucial thing is to find a truth which is truth for me, and to find the idea for which I am willing to live and die.” Truth cannot be mediated by society, science, or authority. One must orientate themselves towards these things. To summarise it, in Kierkegaard’s words, “Truth is subjectivity”.

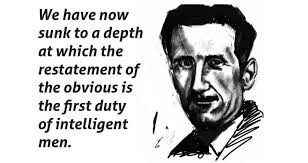

According to Kierkegaard, for anything to be true, it had to illicit passion and commitment. In terms of journalism, Kierkegaard thought that the lack of subjectivity in the Press created a lack of passion and intensity in the public, and led to an age of passionless reflection where people would rather observe what’s happening around them than take any active role in it. Kierkegaard believed that one of the effects of the objective Press was that everyone reading the papers became one collective, anonymous group known as ‘The Public’. The news just became a form of general entertainment describing the world in a pseudo-objective way.

Writing for the New York Times, Matt Taibbi wrote that, “Opinion can’t be extracted from reporting. The only question is whether or not it’s hidden. Everything journalists do is a subjective editorial choice, from the size of headlines to the placement of quotes and illustrations.” Taibbi points out that objectivity is a guise that the Press can hide behind to avoid responsibility. It’s not that facts don’t exist, but rather simply hiding behind the facts to distance yourself from your own bias is wrong.

So if Kierkegaard pointed this out some hundred years ago and Eagleton expanded on it more recently, why are we still hung up on an objective form of journalism? The idea could be said to have been popularised by 20th Century journalist and media critic, Walter Lippmann. Lippmann thought journalists needed to incorporate the scientific method into their reporting, and believed that presenting citizens with impartial news would make them better informed and the Democratic process would be strengthened - otherwise known as Informed Consent.

While Lippmann seems to be well-intentioned, the reason objectivity in the news seems to have become so popular in the 20th Century had little to do with Democratic aspirations. Instead, the real driving-force behind the push for objectivity in the media was advertising. As the Press grew into a full-fledged industry, advertising became the largest source of media revenue. As a result, having a narrow audience with a specific political slant was a business liability. If a newspaper only focused on offering a Socialist perspective on political events, advertisers wouldn’t be interested. Or worse, a paper with the opposite viewpoint might spring up and take away half of your market share.

Media Scholar Gerald Baldasty notes that 19th Century advertisers, “Wanted less criticism of public officials and reminded publishers that partisanship hurt circulation, and consequently, advertising revenues.” Even if you had a widely read paper with a specific political leaning, that leaning might have also scared away advertisers, dooming your business from the get go.

In 1988, Edward S. Herman and Noam Chomsky published their ‘Manufacturing Consent’. The two argued that plenty of papers throughout history were more widely read than their allegedly more objective competitors, but a lack of advertising meant they were either put out of business or bought by their rivals. Once the latter option occurred, their coverage began to resemble the more ad-friendly coverage of their parent company. Offering an objective perspective became a codeword for remaining advertiser-friendly and appealing to the widest audience possible. It's much like Kierkegaard predicted: the Press would turn individuals into one big anonymous public. In this case, the anonymous public is made up of consumers who can make money for both news sources and advertisers.

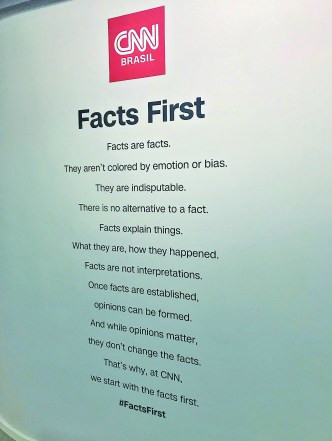

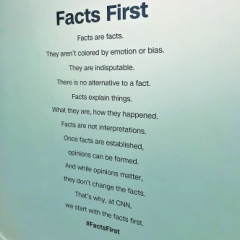

This connection between journalism and commerce shouldn’t be surprising in light of our 24 hour news cycle where people like CNN’s (whose motto is “Facts first”) head Jeff Zucker have no problem acknowledging the network is providing entertainment, even comparing it to sports: “The idea that politics is a sport is undeniable, and we understood that and approached it that way.” Things are a little different to when ‘Manufacturing Consent’ came out in the 80s - for one, mainstream media has splintered into Conservative outlets and Liberal outlets - but the basic principles are still there: newspapers and media outlets are selling a product to advertisers and that product is...you.

The book argued a series of filters defined what kind of stories corporate media could report on and how. One such filter was simply corporate ownership. Because the news media is dependent on advertising money to make profits, they directly benefit by serving the political and financial interests of the TV networks and corporate entities that pay them. If coverage of a story would alienate the Board of Directors, or worse, the Marketing Department, adjustments will be made. According to Herman and Chomsky, much of what we are served as objective news is just propaganda for the powerful. It’s not that journalists are bad, but that many have to work in the constraints of news as a business.

Brent Cunningham, Managing Editor of ‘The Columbia Journalist Review’, thinks that a reconsideration of the values of objectivity can, “Provide a window into a particular failure of the Press: allowing the principle of objectivity to make us passive recipients of the news, rather than aggressive analyzers and explainers of it.”

While I titled this article ‘Can the news be objective?’, the better question may be, ‘Do we actually want it to be?’ To which we would most likely respond...probably not, at least not the way most people think about it.

But then again, perhaps not. Postmodernist Jean Baudrillard argued that it isn’t a lack of access to information that renders the news meaningless, its the proliferation of images that makes it so untrustworthy. If you look hard enough, you can find the contra-positive, underside, or opposite of any event. These multiple interpretations don’t make the world more accessible - rather the explosion of information and events makes the ability to understand the world nearly impossible.

The camera lens makes every image suspect: war is reduced to theatre, disease into telethon, hunger into magazine covers. It makes the most atrocious events questionable. Every image is passably staged, recreated, simulated for a political end or to push a product. There are hundreds of news channels all competing for viewers, followers, and so on. Media and advertising, as we have already found, operate on the same wavelength and, as a result, the line between reality, marketing, and news is nearly impossible to discern. Media outlets and advertisers used to compete to keep people glued to their couches, perpetually titillated by the explosion of content on the screen, but now they cooperate.

It is the selling of a lifestyle, a promise of access to the truth as something to produce meaning. This is why reporters appear at the scenes of crime, embed themselves into military units during war, and stand on the banks of oceans during hurricanes - the signs of disasters are images to be consumed. While our lives may be boring and mundane, the nightly news reports promise there are places where...things happen. It sells the narrative that meaningful things do happen. They broadcast stories of actual events, but the media creates a copy of an event, they create non-events; xerox copies of reality that are easily ingested by a society that has been trained to accept advertising, suggestion, and disinformation.

We are complicit in this disinformation campaign: people willingly choose deception, the masses want to be tricked, fooled, and distracted from the reality of their lives. As Baudrillard put it, “... The most serious problems posed by advertising derive less from the unscrupulous-ness of those who fool us from our pleasure in being fooled.” Simply put, we prefer the copy of reality over the real thing.

An enlightening read on the nature of objectivity and journalism and a bleak indictment of our relationship with it. A really good read and I kinda want to see how these principles might apply elsewhere...