There is overwhelming evidence to suggest that the value of arts education in state schools is on the decline. Since the introduction of the English Baccalaureate- which does not include any arts subjects- by former Education Secretary Michael Gove in 2010, and with a continued push from Ministers to see 90 per cent of students taking the EBacc by 2025, teachers have been forced to shift focus away from arts subjects. 68 per cent of primary schools have seen provisions for arts subjects decrease in the last five years, while 9 out of every 10 secondary schools has had to cut back on lesson time, staffing or facilities in at least one creative subject in recent years. As authority figures continue to enforce the message that arts subjects are a waste of time- from Ofsted chief Amanda Spielman claiming that academic subjects were the best route to higher education, to former Education Secretary Nicky Morgan stating that studying arts subjects could ‘hold [young people] back for the rest of their lives’- it appears this negative attitude towards arts education is here to stay.

So, do arts subjects in school matter? As someone who benefitted hugely from the opportunity to study a variety of creative subjects, I feel that the government should be doing as much as it can to preserve the quality of arts subjects taught in schools, so that students receive a well-rounded education. But it appears not everyone agrees.

When considering the importance of arts education, many want to see the long-term benefits, specifically the financial ones. As shown by these comments on The Guardian article, ‘It’s clear this government doesn’t value arts in schools’, a lot of people don’t believe that students who study arts subjects will go on to contribute copious amounts of wealth to our economy:

‘As a taxpayer (and high school history teacher), I don't value the arts in school either at a time when we need more and more engineers, doctors and scientists; in short, those who contribute to the material betterment of society.’

‘You don't create wealth with the arts- we need engineers and other technical skills as well as entrepreneurs…Sorry, but as far as I am concerned a classics degree is [expletive] useless to a country that needs wealth creators!’

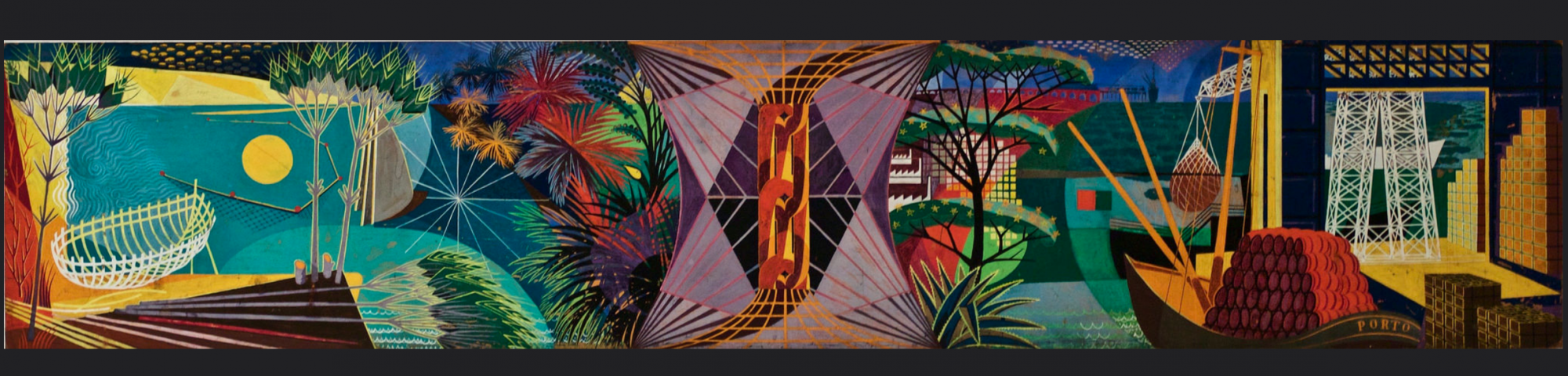

However, this is simply not the case; the UK has a global reputation for being a centre of excellence for art and culture, drawing in audiences from all over the world. As a result, the performing arts is part of the fastest growing sector of the UK economy, contributing more than £100 billion in 2017. The arts industries employ hundreds of people- not just performers- who help to fund a huge amount of our economy, hence it is important the next generation are encouraged to pursue careers in this field from an early age so that this impact on our economy continues to grow.

The Guardian provides an alternative viewpoint in their article, ‘If we don’t protect arts education, we’ll lose the next generation of performers’, which asks readers to consider the benefits of arts education beyond the financial ones:

‘A recent Institute for Fiscal Studies report said that creative arts degrees will cost taxpayers 30% more than engineering degrees because of the lower salaries its graduates will secure, making them less likely to pay off their loans in full. It seems that the rhetoric of student as consumer leads us to the idea of graduate as product. The returns on investment in performing arts are significant, but the strength of any country and its people is about far more than the financial wealth it generates. We must challenge the dangerous narrative that equates success with the level of a graduate’s income and which reduces education to a financial transaction. If we don’t, we risk losing the next generation of artists and all that they contribute to our wellbeing and society.’

This was something that even I, as a working artist hadn’t considered, but it is so reminiscent of the education system I grew up in. At all levels of education, faculty will attempt to impress students and parents which statistics and league table results, but it is almost as if we have forgotten what education is really about. Are we enriching young people’s lives? Are we teaching young people to be inquisitive, critical thinkers? Most importantly, do they have a passion for knowledge and learning? These are things that cannot be quantified. Therefore, the preservation of arts education in schools is vital as its benefits go beyond academic and financial for the individual and our society - they make for a happier human.

Many argue that schools should place an emphasis on academic subjects, as creative pursuits, such as playing an instrument or drama can be done as an extra-curricular activity. As suggested by this comment on The Independent article, ‘Decline in creative subjects at GCSE prompts fears that arts industry could be damaged’, many feel that academic study is not the route to success for aspiring creatives, and thus these subjects should be left out of the curriculum:

‘How many people in the creative industries actually got there, because of academic qualifications? How many artists learnt their trade in GCSE art? Great musicians in GCSE music? Great writer [sic] in English literature GCSE? The answer will be vanishingly small. The creative industries are passions, things people can and do in their own time. You don’t need them in the school system for them to thrive. The same isn’t true of academic subjects like maths, and the sciences. Schools are right to concentrate on giving young people a good academic foundation, the creative industries are never going to be short applicants [sic].’

However, for some young people, it is not that simple. Reports have revealed that families from lower socioeconomic backgrounds are nearly half as likely (19 per cent) to have a child learning an instrument than families from higher socioeconomic backgrounds (40 per cent). As a result, this could continue to push the idea that the arts is an elitist industry. Keeping creative subjects in our classrooms would allow those who may not have the funds to pursue their passions as an extra-curricular activity to seriously consider their chosen career path. With a 2016 Sutton Trust report revealing that over half of British BAFTA and Oscar award-winning actors were private-school educated, it is important that we preserve arts subjects in state schools so that talent from all backgrounds may one day be represented on world stages and screens.

Unfortunately, there is also an unpleasant stereotype that creative subjects are for students who are unintelligent:

‘"My child is arty" is often (not always) really a way of pretending your child isn't just dim.’

Yet there is overwhelming proof to the contrary. Evidence suggests that playing a musical instrument benefits spatial-temporal ability, IQ scores and reading and language. Music education also shows promise for cognitive skills across all age groups. Furthermore, a report by Americans for Arts found that young people who regularly participate in creative activity are four times more likely to be recognised for academic achievement, participate in a math or science fair or win an award for writing an essay or poem.

The benefits of arts subjects in school also go beyond the academic, teaching young people many valuable life skills. One study conducted by the University of Arkansas in 2014 found that young people who receive exposure to creative classroom environments have more tolerance and empathy for those around them.

A study conducted by Brookings also found that an increase in arts education has a positive impact on students’ social and emotional skills. They found that students experienced a 3.6 percentage point reduction in disciplinary infractions and an increase of 8 percent in their compassion for others. Moreover, students who received more arts education experiences were more interested in how other people feel and more likely to want to help people who are treated badly.

When focussing their analysis on elementary schools, they found that increases in arts learning positively and significantly affected students’ school engagement, college aspirations, and their inclinations to draw upon works of art as a means for empathising with others. Students were more likely to agree that school work was enjoyable, made them think about things in new ways, and that their school offered programs, classes, and activities that kept them interested in school.

However, upon closer inspection, much of the research into the benefits of studying creative subjects at school is unfounded. A study carried out by The Conversation looked at 199 international studies, covering pre-school through to 16-year olds, and found that there are just as many studies showing that arts participation in schools has no or negative impact on academic attainment and other non-academic outcomes as there are positive studies.

The study also found no evidence that engagement in visual arts, such as painting, drawing and sculpture, can improve academic performance. Effects on other non-arts skills such as creative thinking and self-esteem were also inconclusive.

Despite this, the producers of this study did not see this as reason to remove artistic subjects from our classrooms:

‘If the arts make children happy and feel good about themselves, give them a sense of achievement and help them to appreciate beauty, then that is justification in itself.’

I feel this is a very important statement; there is much to be said for placing value on something that makes our children happy, and for one moment forgetting if a drama student will contribute anything substantial to the economy, or if GCSE Dance is only for the ‘thick kids’. With anxiety and depression in children up by 48 per cent since 2004, young people need to be encouraged to participate in things that make them excited about life again- and if that means picking up a paintbrush or singing in a choir, then these opportunities should be readily available in schools. And that is why I believe, more than ever, arts subjects in schools really, truly matter.

0 Comments