It’s called Feminist Musicology, and it scientifically studies the same aspects as musicology does, but with a perspective of gender. Traditionally, musicology is the study of music, and it focuses on all aspects of music in all periods of history and cultures. Therefore, Feminist Musicology is the science where feminist theory and traditional musicology merge. Among the many women worth mentioning, Susan McClary and Marcia Citron are two musicologists greatly influenced by feminist theory and the principal precursors of this new approach to musicology.

The growing feminist ideology from the end of the 60s and the 70s exerted a great influence on the birth of this new field of study. Women demanded nothing more and nothing less than to be visible; that there should be a version of history that recognised their importance. Thus arose this new branch of musicology, whose objectives include the analysis, research, visibility and recognition of women, specifically in music.

This timeline reflects on the most important aspects of this science and its evolution through time.

1970’s: Feminism meets traditional musicology

The feminist movement was born around the 1840s. Their biggest goal was to live in a world where women weren’t oppressed anymore, in every aspect of society and, of course, culture.

In the 70s, historians and musicologists turned back to look at women’s participation in music history and listed some of the most influential composers and performers. In anthologies like “Historical Anthology of Music by Women” by James R. Briscoe, essays like Karin Pendle’s “Women & Music: A History”, and books that told the story of unknown female composers like “Women Composers: The Lost Tradition Found” by Diane Jezic, researchers brought to light many compositions and composers from the past that had remained uncovered - and underrated.

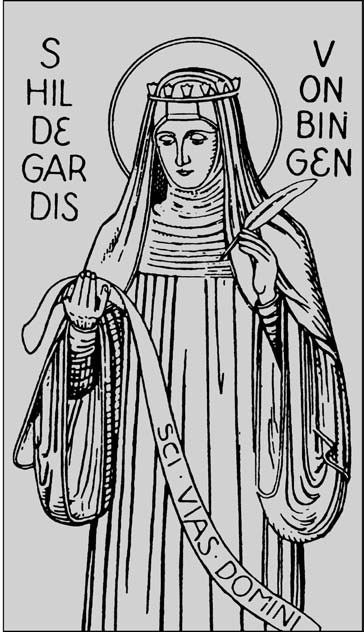

Among others, they found works by Clara Wieck Schumann, Hildegard von Bingen, Ethel Smyth and Barbara Strozzi. As to why their works had been forgotten, musicologist Jane M. Bowers stated in her book, “Feminist Scholarship and the Field of Musicology: I”,

“We have observed that no matter what kind of musical activities women have engaged in, and no matter how vital or distinguished those activities might be, a historical process of making those activities invisible has nevertheless been at work.”

This might just reflect how the ideology of essentially patriarchal societies kept these women’s music underground.

1980’s: Challenging the aesthetic and the classical repertoire

The increasing number of data collected by researchers soon began to challenge the traditional discourse of musicology. Feminist scholars then began raising questions regarding the classical music repertoire, one essentially male-dominated and that responded to male aesthetic values. In this matter, Karin Pendle raised the question,

“Do women have any authentically female experience unconditioned by patriarchal oppression and constraints?”.

Many controversies have arisen in music as to the difference between “feminine” and “masculine”. The first was often associated with emotional, lyrical or passive themes, while the second was used to refer to active and prominent characteristics. This vision was clearly a result of the constructions of “masculinity” and “femininity” in the past centuries, one that suggested that men were “intelligent and strong” and women were “emotional and weak”.

Even more so, when women in the 19th century composed “masculine music”, they were told to be daring and criticised for “challenging their feminine nature”. But to keep composing according to this “feminine nature” was to compose what society expected them to. The case of Clara Schumann is one that differs from the rest; she was considered to be almost “above gender”, somehow escaping male criticism. But this wasn’t the same for other female composers like Fanny Mendelssohn, who was strongly discouraged by her father and her brother Felix.

By the late 1980s, the subject gained more interest when the American Musicological Society began to accept papers and panels on feminist theory and criticism. By 1898, the society offered the first workshop on this subject.

1990’s – present-day: an established academia

By 1991, three international conferences held in England, Minnesota and Holland made feminist and music theory their focus. That it was now a topic of debate at international musicology conferences increased the interest of scholars in the subject, which motivated the growth of Feminist Musicology as a subject even to this day. Now established academia, Feminist Musicology remains a field of interest for researchers, historians and musicologists.

Today, it is impossible to study music history without mentioning Fanny Mendelsohn, Hildegard von Bingen, Amy Beach (who became the first president of the Society of American Women Composers), Clara Schumann or Maria Anna Mozart. It is to be hoped that the contributions of the researchers who started it all back in the 70s, and the increasing number of specialists working in this field, will uncover even more long-forgotten works by female composers. It is hoped that this will create a society where the pre-existent patriarchal precepts do not oppress female musicians, and their music is not kept aside.

0 Comments