Paula is presenting the same Q&A to each participant to draw on common themes and encourage a wider dialogue to support pathways. A core concern at Talkin’ Culture is how the Arts landscape is being compromised in terms of the Equality Act through severe funding cuts. For example, unpaid placements and internships exclude who can afford to enter the pipeline by other means despite being qualified. Talkin’ Culture agrees with major reports that factors like this are an Equality Act issue. Over the course of these blogs Paula will invite emerging conservators to do the talkin’ including their suggestions for positive change to address equality and sustainability in this sector. We hope constructive comments and ideas will be shared in support of equality, sustainability and the endangered list of crafts.

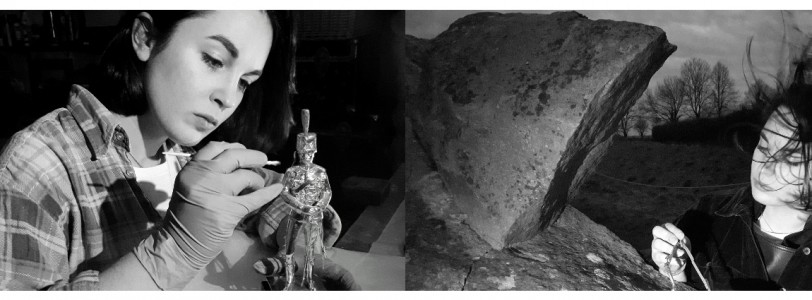

Talkin’ Culture Talks to Francesca Levey www.flmetalconservation.com

Francesca specialises in Iranian and South Asian arms and armour between the 16th and 19th centuries.

Did you have an easy and obvious route into historic conservation?

I wouldn't describe my route into conservation as an 'easy' one, but I do think it was reasonably straight forward once I did my research and got a plan together.

I didn't really know where to start until I heard about West Dean College when I was sixteen. I remember going to an open day with my mum on the advice of an artist friend and meeting the then metalwork tutor, Jon Privett. I was captivated by his explanation that 'in order to be able to fix or conserve something, you first must understand how things are made.' I thought this was infinitely sensible and tailored the rest of my education around getting to West Dean to read a metalwork conservation masters. My rational was that if one needs to understand how objects are made in order to fix them, surely one should also understand the context from which they come. I therefore did my bachelors in Art History at the Courtauld Institute.

How were your interests supported?

My interests were not really supported by anyone other than my parents in the early days. Despite attending a private school, it didn't offer any metalworking/craft courses or a history of art program, so I did my best to gather the skills I thought I would need by studying English literature, fine art and philosophy.

Have you had to take on unpaid work, unpaid internships or have you been expected to work for nothing to gain experience?

Yes, I interned at a national museum for a year whilst I was in my third year at the Courtauld but that did lead to a wonderful job. I also did unpaid work experience with the National Trust and with a bronze foundry.

Is pathway information to study and work in historic conservation easy to find?

I didn't find it so, but that was almost a decade ago and I think that conservation programmes have become slightly more visible in that time. I was very lucky to have the advice of a BADA member (British Antique Dealers Association).

What makes you persevere?

-The ability to use both my mind and my hands in every day work.

-The fact that I am helping to preserve craft skills as well as objects

- A deep love for the objects I work with and a desire to not only preserve them for the future but to tell the stories that are such an important part of them.

What are your biggest challenges as a qualified, emerging conservator?

Finding a secure job. It's not that the work doesn't exist but that institutions either don't have the funding to employ conservators or that their priorities are more focused on activities that generate revenue, due to continued cuts. As a result, most employment is short term contracts, permanent jobs are rare and competition is always fierce.

I set up my own private practice on realising that there was a demand for my skillset but not one that an institution was likely to be able to fill for more than a few years. That was a huge challenge both academically and financially. All my savings were spent on attaining my conservation Masters so there was nothing left when it came to setting up the business which was a bit of a struggle. Conservation resources are seriously expensive! The biggest challenge however was working alone. Not having a mentor or colleague to turn to and confer with about treatment options has been very tough. I am lucky that I can go and do the research required and call on colleagues for advice in tricky or uncommon situations but that means the treatment takes longer and I earn less by default.

Biggest high and low so far?

Biggest high: Realising there was enough demand for my work to set up private practice.

Biggest low: Clients quibbling over the bill or changing their minds at the end of a difficult treatment.

Do you think historic conservation skills are valued and understood in the mainstream?

Sadly, no. I am sure my colleagues will agree with me when I say that nine times out of ten when people ask me about my job the response is 'oh I love pandas!' and even with an explanation making the distinction between restoration, conservation and making is still tough. I don’t think conservation skills are necessarily always understood and valued within a museum context either. There have of course been high profile conservation treatments and that’s great, but for the most part the title of 'curator' commands much more respect and understanding than 'conservator'. We tend to be the background people and rarely have much in the way of exposure and I think that a lot of that is down to people not really understanding the role. Curators aren’t the only story tellers.

If you summarised your risks what are your rewards?

- Really getting to know objects, their owners and makers. It is always such a privilege to be able to get so up close and personal with them. I often find that even if I have photographed an object a thousand different ways and seen it a hundred times, when I have it on the bench or in my hands there is always a little detail that I will not have noticed before, be that a tool mark, an area of wear or just the subtle patina that makes it so charming.

- The balance between academic thinking and practical hand skills. A technical understanding of the objects, how they work and the techniques that have been applied to them is really key in getting the best treatment. That’s one of the things that really drew me to the profession.

What are your recommendations to improve fairer conditions for new entrants into historic conservation?

It would make a massive difference to get rid of unpaid internships, for institutions to be more open to accepting candidates without prior experience in order to help break the 'need experience to get experience' trap and of course, more funding into the arts sector.

I think one of the biggest challenges we face is that conservators are not really valued as highly as they perhaps might be. For example, I attended an exhibition a year ago where the exhibition co-ordinator spent half an hour telling the group about the £35,000 temporary structure the museum commissioned for the exhibition and how special and expensive the structure (a shiny, cigar shaped wall for hanging photographs on) was. Yet at the end of the talk I asked how many conservators they had working at the institution and they said they sadly didn't have funds for any permanent conservation staff. The art world needs to sort out its priorities! After all, without conservators there would be no art works to display!

My huge thanks to Francesca Levey for taking part, authentic voices matter and our next Q&A blog follows next week.

This is a really fascinating read! It explains what being a conservator means and explains why it's a creative role. I'll quote Jon Privett's explanation that 'in order to be able to fix or conserve something, you first must understand how things are made' when I'm talking to museum people about the museum roles that Arts Award includes under the catch-all term `artist'. Congratulations to Francesca too for following what she knew she wanted to do despite all the challenges and lack of support from her school.