Could you please first introduce yourself to the reader?

Hi, I’m Hannah Hobson, a scientist turned science communicator. I live in London and I work at Understanding Animal Research (UAR), a non-profit organisation that works to inform the public on how animals are used in scientific and medical research.

How would you describe your job? What does a typical day look like for you?

I’ve worked at UAR for over five years and my role as Communications Manager means I spend a lot of time working with different people like researchers, journalists, and other science communicators to develop strategies and campaigns that aim to explain to the general public how and why animals are used in research.

We don’t fund or carry out animal research at UAR, but we work with people who do. Working with experts such as scientists and regulators is really important, it means the resources we are creating are accurate and factual.

No two days in the office look the same for me. Some days I could be working with my colleagues to develop digital resources for the general public – things like creating infographics and videos for social media, website articles and interviews, responding to media requests, or myth-busting misinformation. Other days I might be working with member organisations on their animal research communication strategies. Openness in animal research communications is an important part of the work UAR does, so I spend a lot of time encouraging organisations that carry out and fund animal research in the UK to share more information about their research with the public and press.

How did you get into the creative industry? What was your career path to this point?

My background is traditionally science based. I studied Forensic Science at university, followed by a Masters degree in Toxicology. I worked as an analytical chemist and spent almost five years managing research studies at an agrochemical company. Eventually I realised that I wanted to move away from research and into a communications role.

While my job isn’t a traditionally creative role, working in communications, even in the scientific sector, requires creative thinking to make scientific concepts understandable to the majority of people. Historically, science has been seen as an elitist subject with lots of complicated words and confusing concepts. I’ve always felt passionate about making science accessible to everyone and encouraging young people to study STEM beyond school, especially women as the sector is still heavily dominated by men.

Working in communications is really exciting, you get to meet all sorts of researchers, from people just starting a career, to Nobel laureates. Being able to turn their research into content that the public can resonate with is a really rewarding experience.

And what drew you to working at Understanding Animal Research?

Due to my studies and previous research jobs, I’d always been familiar with the use of animals in scientific research. The majority of my friends and family do not have a scientific background so I knew first-hand what it was like to try and discuss this sensitive topic with them, and the sort of misinformation that existed.

Historically, animal research has been quite secretive due to extremist activity. Back in the 1970s – 1990s there wasn’t a lot of information readily available, so people assumed the worst and scientists didn’t talk about their work for fear of being targeted. In the early 2000s, the UK government took action and cracked down on illegal activism. Since then, organisations have become more open and are sharing more information about the animal research they carry out in order to aid public understanding and fight the spread of misinformation.

When I saw my job being advertised at UAR I knew it would be a great opportunity for me to use my skills to help explain an area of science that really mattered to me. I didn’t have much communications experience at the time, but my background and passion for fighting misinformation was enough for my colleagues to give me a chance.

What are your own views around animal testing?

In order to develop new drugs and medicines that treat, cure and prevent diseases like cancer, cystic fibrosis, Alzheimer's, HIV/AIDS, malaria, and Covid-19 we need to employ a huge range of scientific tools, and research using animals is an essential part of this process.

I believe that animal testing should only be carried out when it is absolutely necessary. This means that animals should only be used in research when there are no viable animal-free methods, and when the potential benefits of the research outweigh any suffering the animal is likely to experience. I also believe that research animals should be cared for as humanly as possible, which includes minimising suffering with things like painkillers whenever possible.

Fortunately, these parameters are also enshrined into the UK law, Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986. For an animal experiment to take place in the UK, not only does it have to meet the above parameters, but it must be approved by the Home Office’s Animals in Science Regulation Unit, and by an ethics committee at the institution carrying out the research.

Do you think there will ever be medical innovation that doesn't require animal testing?

Refinement, reduction, and replacement of animals in research are really important aspects of research involving animals. This means minimising suffering  Provided by UARand improving animal welfare, reducing the number of animals used to the minimum that will produce viable results, and replacing animals with animal-free methods whenever possible. The government-funded National Centre for the 3Rs (NC3Rs) funds work in all these areas and as a result many techniques have led to the replacement of animal tests.

Provided by UARand improving animal welfare, reducing the number of animals used to the minimum that will produce viable results, and replacing animals with animal-free methods whenever possible. The government-funded National Centre for the 3Rs (NC3Rs) funds work in all these areas and as a result many techniques have led to the replacement of animal tests.

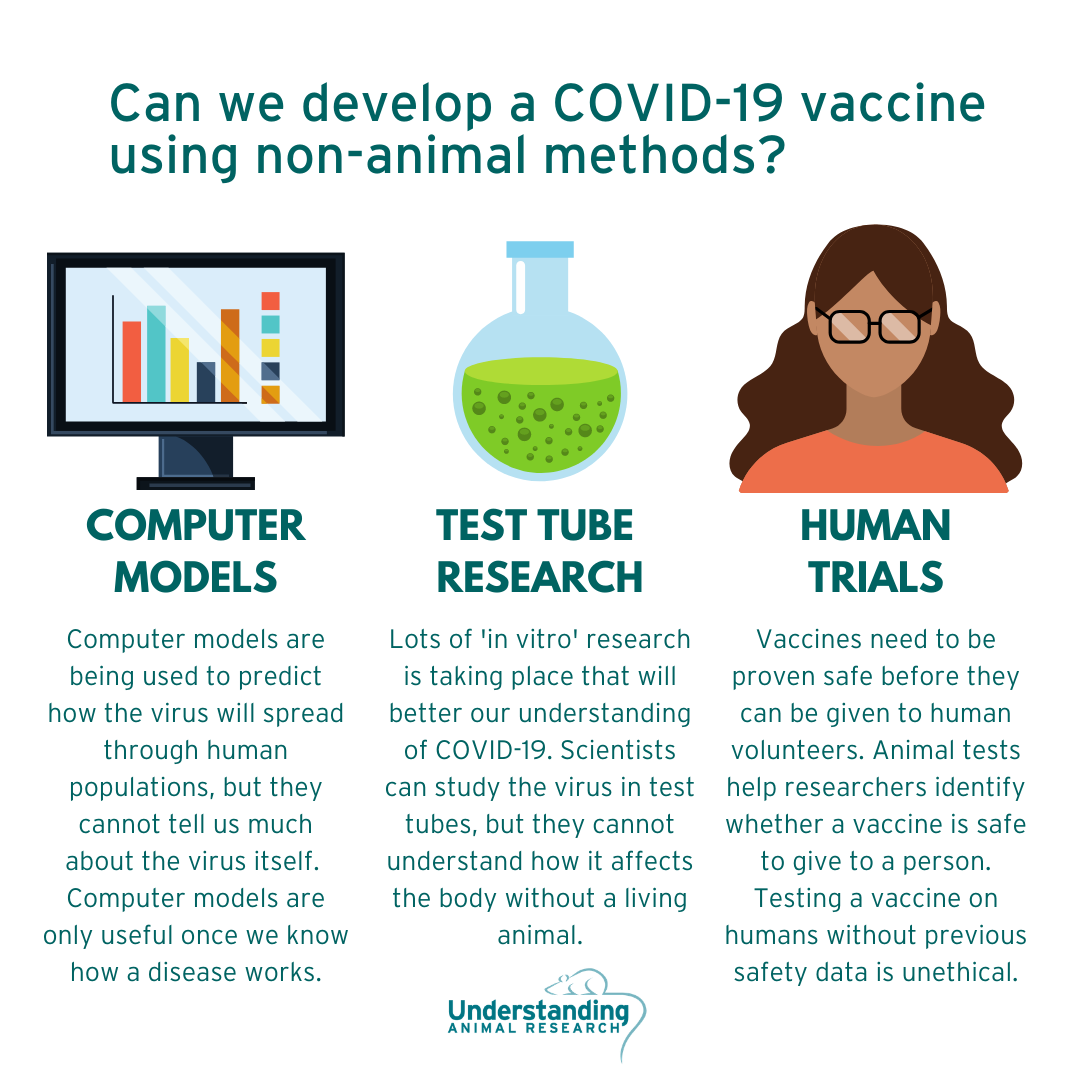

We are now able to grow organoids in the lab and use powerful computer programmes to predict the safety and effectiveness of a new compound. However, these techniques are unable to replicate a whole living organism, which is why animal research is still essential for the development of new medicines.

On the other hand, cosmetics (and their ingredients) are no longer tested on animals because there are animal-free methods that exist to see whether they are safe for people to use. Animal testing for cosmetics has been illegal in the UK since 1998 and is slowly being banned all over the world.

One day I hope that science progresses enough that animal testing is no longer required. We are not at that stage yet, so it’s important we continue to fund organisations like the NC3Rs.

Are there any misconceptions around animal testing that you want to challenge, or correct?

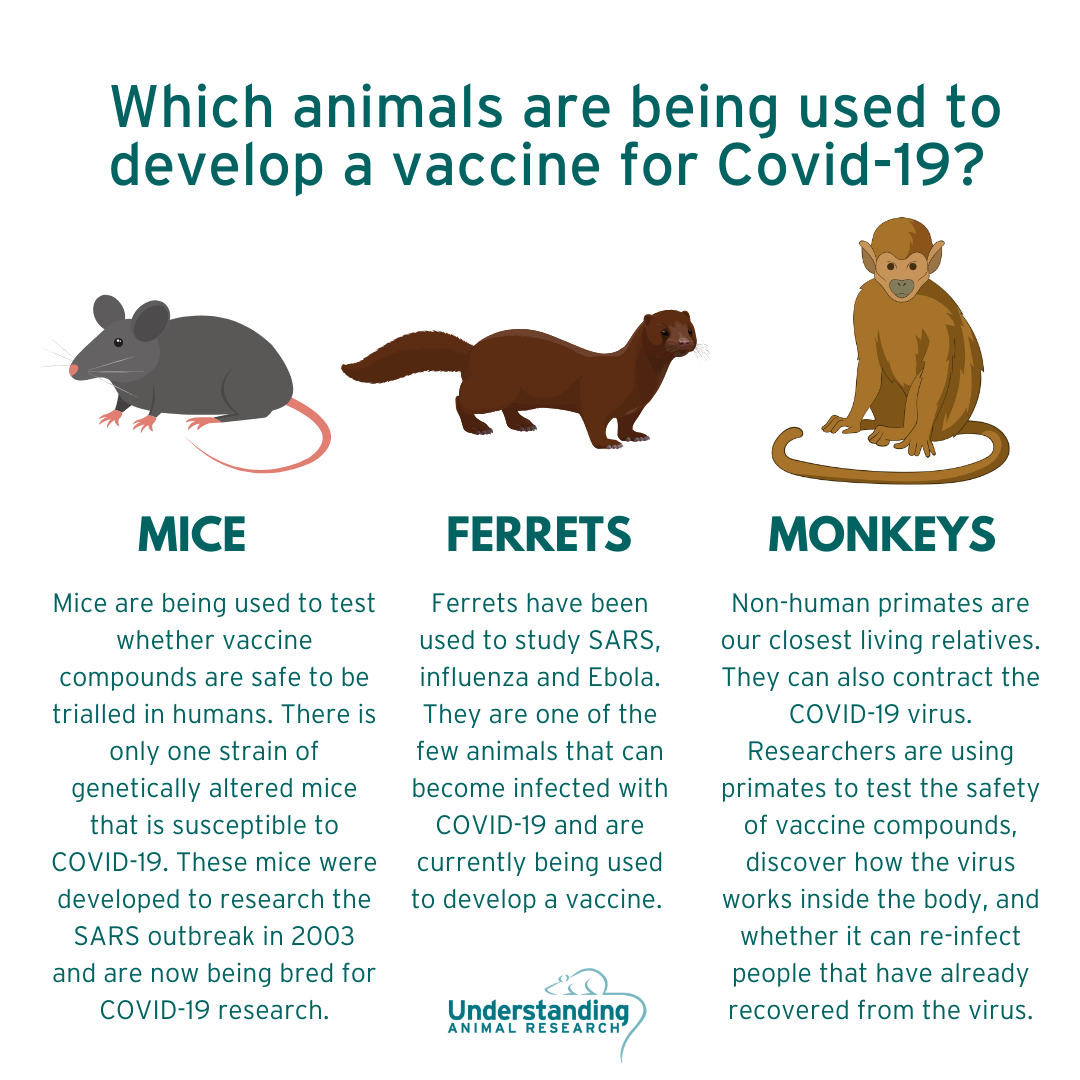

The biggest misconception is that humans and animals are nothing alike, therefore animal research is futile. Mice, which are the most used research animal in the UK (75% of animal research involves mice) have over 90% of the same genes as people. We have the same internal organs and, in the majority, of cases we respond to drugs in the same way. This is why mice are so good at predicting whether a new drug is safe and effective.

Another misconception is that the people involved don’t care about the animals. This couldn’t be further from the truth. In my experience, animal research laboratory technicians are some of the most passionate and responsible animal carers you could possibly meet. Animal welfare is their number one priority, and they are highly trained.

Some of your latest work has been detailing the Covid-19 vaccines. Can you talk us through what that has entailed?

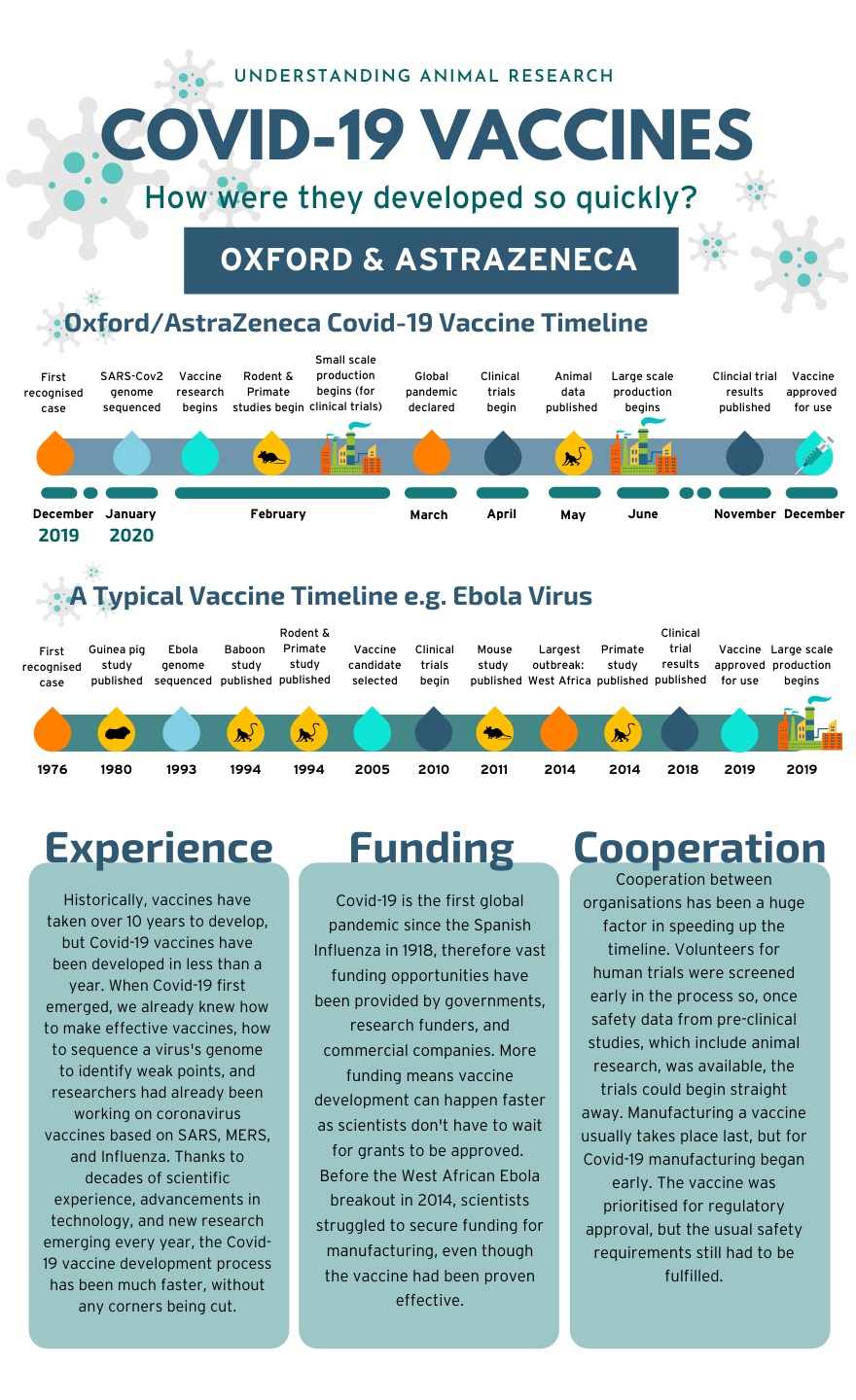

Animal research has been an essential part of developing Covid-19 vaccines. The Oxford-Astra Zeneca and Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine have both used mice and monkeys to determine the safety and effectiveness of the vaccines. Using information from experts involved in the process, we have developed content that explains how the vaccines have been developed and at what stages animal research takes place, and why. We have created infographics, videos, and website articles to make this information available in the most accessible of ways.

There has been a lot of content on social media around the Covid-19 vaccine process, and people have been concerned about how quickly the vaccine has been developed. Why shouldn’t they be?

You shouldn’t be concerned. The Covid-19 vaccines have been developed in record breaking time, not because the research was rushed or steps were skipped, but because there has been a huge investment of time and resources like never seen before. Provided by UARYou’ve probably heard the statistic that vaccines take around 10 years to be developed. That’s because researchers usually spend an awful lot of time sourcing funding. During Covid-19 vaccine development huge sums of funding were available. This meant researchers could recruit clinical trial volunteers early in the process so trials could start as soon as the vaccines were proven safe in animal studies. Pharmaceutical companies also started manufacturing the vaccines early in the development process, instead of waiting until all trials were completed. Due to the SARS and MERS breakouts, research into coronaviruses had already been taking place for years so we already had a head start in understanding how to make a coronavirus vaccine.

Provided by UARYou’ve probably heard the statistic that vaccines take around 10 years to be developed. That’s because researchers usually spend an awful lot of time sourcing funding. During Covid-19 vaccine development huge sums of funding were available. This meant researchers could recruit clinical trial volunteers early in the process so trials could start as soon as the vaccines were proven safe in animal studies. Pharmaceutical companies also started manufacturing the vaccines early in the development process, instead of waiting until all trials were completed. Due to the SARS and MERS breakouts, research into coronaviruses had already been taking place for years so we already had a head start in understanding how to make a coronavirus vaccine.

Covid-19 vaccines are safe and effective, please get one if you can.

And another concern is around the long-term effects of the vaccine. Do we need to be worried?

You don’t need to be worried. We have been using vaccines for decades and they are incredibly well understood. Unlike medicines which you might take every day for weeks, months, or even years, vaccines are usually administered once or twice, which means long term effects are incredibly rare. The work on the Covid-19 vaccines has been extremely robust and as is the case with all new medicines and vaccines, long-term monitoring will continue now that the vaccines have been approved.

In your opinion, should vaccines be mandatory?

I don’t think vaccines should be mandatory, but I do think people need to understand the serious repercussions of not being vaccinated. Vaccines protect yourselves, the community, and vulnerable people who are not able to be vaccinated so I think more work to inform the public of why vaccines are so important would be great.

Given that a lot of this misinformation is being spread through social media, would you say that sites such as Facebook and Twitter are doing enough to combat it? Are they a net gain or detriment to the efforts to end the pandemic?

Social media is a double-edged sword but, ultimately, I think it’s an important tool for sharing messages and creating spaces to have Provided by UAR conversations. Adding disclaimers to posts about Covid-19 that direct people to the official NHS site is a good place to start to combat the spread of misinformation and make people think about what they’re reading and willing to share. Social media platforms have a powerful influence over people so I’m sure more can be done to highlight misinformation but also to educate people.

Provided by UAR conversations. Adding disclaimers to posts about Covid-19 that direct people to the official NHS site is a good place to start to combat the spread of misinformation and make people think about what they’re reading and willing to share. Social media platforms have a powerful influence over people so I’m sure more can be done to highlight misinformation but also to educate people.

How do you monitor the impact of your work? Is it easy to see how your campaigns change public perception?

It can be difficult to measure the impact of UAR’s work, but ongoing polling is a helpful tool to measure public perception around animal research. We know that two-thirds of the public can accept the use of animals in research if it is for medical purposes, and there is no alternative. While we can’t attribute this figure to UAR’s work alone, our work to engage the public, correct misinformation and encourage openness within the life science sector plays an important role in this. We also know that our work around openness in animal research communications has led to a vast increase in the amount of animal research information in the public sphere.

At the start of the pandemic, we commissioned our own poll and found that when faced with a health crisis, three quarters of people accepted that scientific research using animals such as mice, dogs and monkeys, would be important to developing treatments and vaccines for COVID-19.

If you could change one thing in society right now, what would it be?

On the topic of misinformation, I wish people would spend more time thinking critically about headlines they read on social media. Whether that’s a post someone random has shared on Facebook or a sensationalised headline on Twitter.

Where can people find out more about the work you do?

To find out more about the use of animals in scientific research you can visit the UAR website: https://www.understandinganimalresearch.org.uk/

You can also follow us on Facebook (https://www.facebook.com/UnderstandingAnimalResearch), Instagram (https://www.instagram.com/understandinganimalresearch/), Twitter (https://twitter.com/animalresearch), and YouTube (https://www.youtube.com/user/animalevidence).

0 Comments