Could you first introduce yourself to the reader?

I’m an arts journalist, editor and critic. I’ve worked as an arts reporter, magazine editor, and on the theatre and music desks of Time Out London. As a freelancer, I’ve covered the arts for publications including The Guardian and Guardian Guide, The Stage, The Arts Desk and WhatsOnStage, and reported on disability arts for Disability Arts Online and Disability Arts International. I’ve also lectured and led workshops in arts journalism skills, including a programme with disabled artists at Goldsmiths in association with Disability Arts Online. I’ve got a particular interest in introducing new voices to arts writing and criticism.

What does a typical day look like for you?

This has pretty much gone out the window with Covid-19. Usually at this time of year the arts world is blooming, and I’d be looking ahead to the Brighton Festival in May. These days there’s a lot more home-schooling, Zooming, Nils Frahm-ing and sheer marvelling at the resourcefulness of artists going on.

What do you enjoy working on?

The bit of reviewing if/when your experience genuinely seems to come together in a sentence, the bit of interviewing when the raw materials are in the bag and you get to feel a bit like a sculptor, the bit of mentoring or editing where you’ve helped someone find their meaning or find their voice…

And what do you struggle to get enthusiastic about?

Work-wise I don’t, really. Finding a hook when there doesn’t appear to be one can be an interesting challenge in itself. I’ve sometimes had the experience of being left utterly cold by a show or gig when everyone else around me seems to be completely losing their shit for it. That is also interesting in critical terms, if a bit existentially disconcerting. If I’m struggling with writing, if the words feel dead on the page, it’s usually a sign that whatever angle I’m trying to take isn’t authentic somehow. The arts are endlessly interesting, people are endlessly interesting. If I’m not engaged by someone or something, it’s on me to find another way in.

In February you launched a report with Spectra looking at improving critical engagement with theatre made by artists with learning disabilities. Can you give us an overview as to what the report found?

It identifies and discusses 11 key factors that seem to be contributing to what is a conspicuous gap in critical coverage – from particular misperceptions around professionalism and creative agency, to uncertainty around language, to a lack of diversity among critics and in critical forms.  Spectra - Eat The Stars

Spectra - Eat The Stars

Credit: Timothy Pratt

Many critics were also simply unaware that this increasingly professional, interesting, artistically driven work is out there. You can partly put that down to lack of PR nous/budget. But it’s also true that the fascinating history of learning disability arts has largely gone untold, which has left critics without context, or curiosity. The report also anticipates the key role artists with learning disabilities can have to play in changing all this – when we get better at valuing and enabling those with a talent for ‘doing things differently’.

What was the process for writing the report?

It started with conversations with Kate DeRight, the creative director of Spectra, the neurodiverse company which commissioned the report. Above all, we wanted it to be useful. Many of the questions the report holds in focus have been bubbling away among companies for decades. The productive thing to do seemed to be to bring more critics and commissioning editors in on this conversation. So I conducted over 40 in-depth interviews, consulting on how to make this process accessible. In terms of the actual writing, I remember asking Kate what she didn’t want the report to be. Answer: “A toolkit, or boring”.

And what has the discourse around the report been like?

The aim was to open up a conversation that can benefit everybody, in which the wider theatre industry also has an important part to play. There’s been a lot of initial interest and sharing. But what we’re really after is a steady hum rather than a loud buzz. It feels important that this is something people can engage with in their own time, and in their own way.

One of the report’s findings, in fact, is that there may be a misfit between the sort of rapid cognitive response encouraged by conventional critical models, and some of the theatre made by artists with learning disabilities. I think that goes for the report, too. There’s something here about the verbal velocity of the arts world, generally, and how some of this work might help us all to slow down, to digest, to learn the value of patience.

It’s been great to see publications cover the immediate release of the report. In terms of early reactions, I’m also told it’s galvanised some critics, emboldened other people to speak more openly, and helped some companies “not to feel so alone”. But I’m particularly welcoming hearing from people – like Sam Simms from A Younger Theatre, for instance – who are taking time to absorb it, and work out its relevance to them and their organisations.

Another, very important finding of the report is that we really need to seek new, learning disabled-led ways to have all kinds of discourse around the arts. Hopefully the new ‘digital influencers’ appointed via Disability Arts Online and Access All Areas can help drive this forward. Creation About Face Theatre Company

Creation About Face Theatre Company

Can you talk more about the reluctance reviewers have to be critical of work produced by disabled artists, described succinctly by Neil Cooper as ‘liberal guilt’?

So interesting, this. Artists with learning disabilities are calling for more negative feedback. Companies like Mind The Gap even say they celebrate this kind of feedback more than anything else – because it can be constructive for artist development, it acknowledges their professional status, and it’s so goddamn rare.

There is still a massively widespread (mis)perception that people with learning disabilities are vulnerable – as opposed to ‘sensitive’, of course, because being sensitive is a sign of a true artist, right? – and need protecting. Hence, presumably, the critic cited in the report who decided they wouldn’t file a review of Access All Areas’ Eye Queue Hear, because “I don’t want to upset anyone”.

But there’s another shade to this reluctance to be critical. Many critics want to support and encourage marginalised artists (Lyn Gardner, in the report, comments that, “there is probably something that goes on for all of us critics when confronted by a piece of work by learning disabled artists where you go, ‘oh god what if I really hate this? And how am I going to find a way to write about it that is non-judgmental in some way?’”)

What has been lacking is open dialogue about what support means in this context. At the moment, many artists with learning disabilities are feeling actively discouraged by blanket, un-nuanced and unconstructive praise.

How do we overcome that, especially when Twitter breeds a cancel culture that is so ready to attack?

One approach to the above that has worked for a company like Blue Teapot in Galway is to sit down with critics and directly invite them to “be honest”. Another answer that emerges in the report is for companies to communicate the often extensive work they do around critical and reflective practice, and the support artists are given to encounter both positive and negative reviews.

But sometimes it’s just a critic’s responsibility to stick your neck out. That doesn’t mean hatchet jobs and clever quips. It means holding things up to scrutiny – including, if you’re doing your job right, yourself. I think Twitter has made that feel like an increasingly risky thing to do. It’s also an increasingly hard thing to do well – to do with context, and with nuance – in the face of shrinking word counts, ubiquitous star ratings, narrowing editorial agendas, the lack of professional development for critics, or even, frankly, the lack of payment so much of the time. Good criticism can, and should, offer an antidote to call-out culture. The report finds that companies could do more to connect with emerging critics and alternative platforms where this sort of writing is flourishing.

I hope the report will help companies understand some of these pressures on critics. Petal Pilley, the artistic director of Blue Teapot, suggests the sector could take some more responsibility for supporting critics to engage. She says, “People are terrified to fuck up and be un-PC. I think everyone has to relax the hair-do and let people be offensive unintentionally – to not hold such a defensive position and to maybe be a little more supportive of critics, a little bit more helpful, more kind. Because it’s often ‘the big bad people who are going to come and mark us’! Give somebody the space to have a journey around this. I think that lead should come from us.”

That said, there are still plenty of critics out there who do need to do more to educate themselves, to interrogate their responses, to weigh their words, and to stop huffing and puffing about what is on one level a long-overdue stripping of privilege.

I was also interested in your mention of moving beyond the critic when looking for critique. It extended beyond the remit of the report so you didn’t reflect much upon it, I was wondering if you could do so here?

One of the findings is that there is scope for companies to be bolder and more creative in imagining the sorts of critical conversations they would like to have, and more open-minded about who they might have them with. Lyn Gardner has especially insightful form on this particular topic, and writes about developing ‘critical friends’.

Companies of all kinds can get hung up on reaching the same handful of (usually national newspaper) critics. This can feel a bit all or nothing. Given the still pretty homogenous nature of this critical pool, it also seriously limits the discourse. Lawnmowers, a company based in Gateshead, have a wonderful poster quote describing their show MIST as ‘the “I, Daniel Blake” of PIP reassessment shows”. That didn’t come from a critic, it came from the director of the Centre Against Unemployment.

But of course this is a huge ask for companies who still feel stuck, after decades, at the stage of having to prove they’re professional – companies whose adult artists still get referred to in some quarters of the media as ‘children’. You can see why a quote from The Guardian would feel like a desirable shorthand for “Take. Us. Seriously!”

Going forwards, do you think the balance, or emphasis, between the response of a professional critic and the public on social media will shift?

Read Exeunt editor Alice Saville on the deeply, deeply problematic notion of the ‘expert’ and the ‘professional’ in theatre criticism.

I’m sure it will continue to shift. You can still see arts criticism pulling in two directions: trying to mimic social media on the one hand (your 10-word ‘verdicts’ accompanying reviews), and becoming more the preside of academics on the other. The arts world definitely has a decision to make about what it values criticism for – whether, ultimately, it’s just one tool in its marketing strategy – and to then put its money where its mouth is. This was the first question I put to artists and companies in the research: what value do reviews have for you? The answers ranged from the commercial to the creative, to something much bigger – for these artists in particular – around being acknowledged as a valued part of society.

In your research, did you get a feeling that the industry is generally making positive steps in the right direction?

Many of the critics and commissioning editors I reached out to seemed to get, very quickly, why this was an interesting and important question – and were generous with their time, thoughtfulness and honesty.

That all felt very hopeful, and will probably have surprised companies who have come to feel that critics “just aren’t interested”. But arts criticism is on the bones of its arse and often quite literally can’t afford to have the sorts of conversations it might otherwise choose to.

The wider arts world definitely needs to raise its game: venues, programmers, funders, you name it. The report finds that where a show is on, how long it runs for, and how it is marketed, all has a huge impact on whether it registers with reviewers at all. Funders also need to be aware of the impact of insufficient, inconsistent funding on these companies’ capacities to develop meaningful relationships with critics – and of the need to find alternative ways of funding theatre criticism. And the theatre industry as a whole needs to be more proactive in inviting, and enabling, artists with learning disabilities to be an active and valued part of the wider theatrical landscape. Otherwise, discussion of this work is in danger of being limited to a disability context, and wrongfully dismissed by commissioning editors as “worthy”.

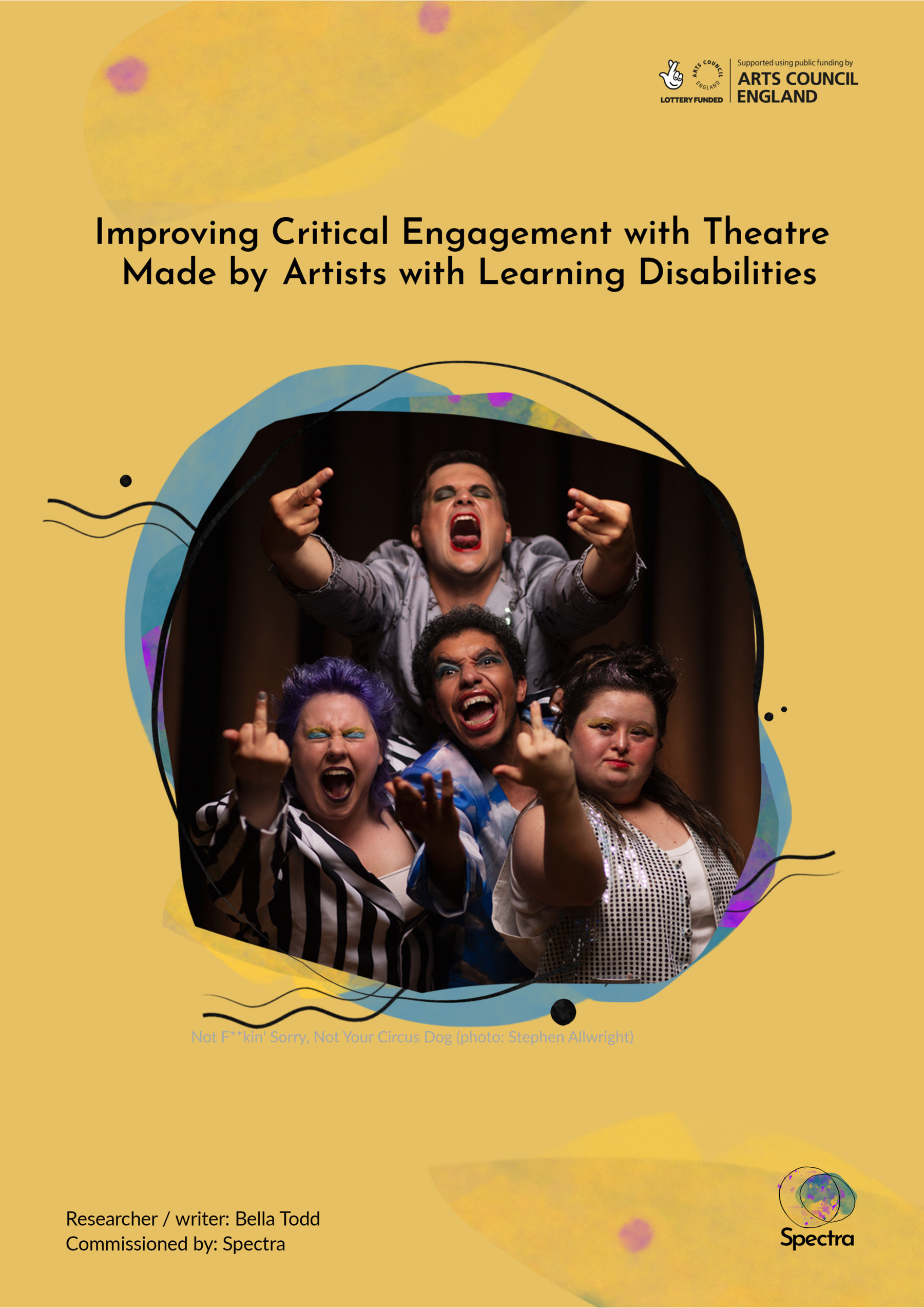

Report front cover

Report front cover

(Featured image is Not Your Circus Dog, Not F**kin' Sorry, credit Steven Allwright)

Do you have plans to explore any other areas of the industry?

The hope is that this report will feel useful and relevant beyond one specific area of the industry.

Where can people find the report?

You can view the full report and the executive summary here https://wearespectra.co.uk/2020/02/09/launch/ (Spectra is committed to making these documents available in a variety of accessible forms and formats. To make a suggestion, please contact Spectra’s Artistic Director, Kate DeRight: [email protected]). This page also includes social media details for anyone wishing to join the conversation @Spectra_Arts #acalltocritique You can also read a feature about the project on Exeunt.

And where can people find out more about you?

If you scan right down to the bottom of my iPhone notes, the final item, dating back over nine years now, is ‘do freelance website’. I don’t think my heart’s really in this self-publicity thing.

Anything you want to let people know about?

The continuing work of the many companies and organisations featured in the report, who will be facing even greater challenges now in the face of Covid-19 (About Face, Access All Areas, BLINK Dance Theatre, Blue Teapot, Dark Horse, DIY Theatre Company, Drag Syndrome, Headway Arts Inclusive Theatre, Hijinx, Hubbub Theatre, The Lawnmowers, Lung Ha, Mind The Gap, Not Your Circus Dog, Open Theatre, Spectra). I’ve got my fingers crossed for Crossing The Line, a pan-European theatre festival celebrating artists with learning disabilities, produced by Blue Teapot and set to take place in Galway, Ireland in May. It’s also going to be worth keeping an eye on the ‘learning disabled digital influencers’ appointed through a partnership between Disability Arts Online and Access All Areas – which include Cian Binchy, one of the actors who contributed to this report.

Beyond that, Disability Arts Online is always a brilliant read/listen/watch. Essential for anyone interested in the arts and society, and with an appetite for strong (and often darkly witty) counter-cultural voices.

0 Comments