Despite Christmas being a Christian holiday, its origins and many of the traditions we partake in when celebrating it, come from much earlier religions and their festivities.

Midwinter has always been sacred, and people have seemingly also always chosen to mark that sacredness with fun and even a little debauchery. These pre-Christian roots of Christmas have also always been especially hard to shake off, with author Stephen Nissenbaum noting, “Christmas has always been an extremely difficult holiday to Christianize”.

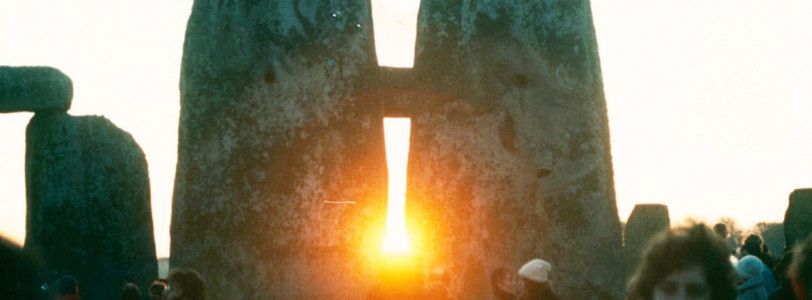

Communities have been celebrating or marking the winter solstice for thousands and thousands of years, and still do so to this day. The winter solstice is the shortest day of the year, usually occurring on the 21st or 22nd of December, and has held significance to many cultures as a representation of life, death, and rebirth, as it marks the start of the days beginning to grow longer again. Stonehenge itself is thought to have been built so as to orientate towards the winter solstice sunset.

The Christmas tradition of heavy eating and drinking may come from this time. It is believed that people would slaughter most of their cattle or livestock so they wouldn’t have to feed them through the harsh months of January and February, meaning there would be plenty of fresh meat to eat during the solstice. Any alcoholic drinks made during the year would usually have been fermented and be ready around the solstice also.

Although traditions changed and altered over the years, this part of the calendar remained a significant festive period, and so, when Christians were attempting to promote the celebration of the birth of Christ, they set the date around the solstice so as to better appeal to pre-Christian cultures. In fact, even once the celebration of Christmas had become the norm, it still for some time shared more similarity to the revelry-orientated pre-Christian midwinter celebrations, focusing more on feasting, drinking, and celebrating life and death than pious observation of “the birth of our Saviour''.

Even Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol is a testament to this – the morbid nature of the story is in line with the long tradition of Christmas being a time to tell ghost stories, a remnant of the observation of midwinter as a point of both death and reincarnation. The Ghost of Christmas Present in the story also reflects ideas of a Father Christmas type figure at that time – ideas that were more aligned with pagan ideas of the Green Man or pre-Christian gods of winter. The idea of Father Christmas has become more commercialised, child-friendly, and even Americanised in our modern interpretation.

Some elements of what we know as Christmas today may also have come from the ancient Roman festival of Saturnalia, in honour of the god Saturn. Like other midwinter celebrations it was a time for feasting and drinking but it was also a time when laws were suspended, gifts were given, and roles were reversed. Gift-giving and revelry have their obvious ties to current Christmas festivities, but role reversal is also something that can be traced to current Christmas traditions.

The role reversal is thought to have included mask-wearing, cross-dressing, and other freeing activities, but most of all was concerned with allowing those who were oppressed in society a period of equality with their oppressors. Enslaved people were given feasts, either dining alongside the people who had enslaved them, or being served by them. This could be reflected in the Christmas tradition of focusing on charitable donations, and helping “those less fortunate” at Christmas time (although just like with Saturnalia you have to wonder why this is considered socially acceptable only as a once-a-year event rather than a year-round cultural re-shift).

The mask-wearing and cross-dressing of Saturnalia may also have ties to this Christmas tradition of carolling, as they may have influenced the midwinter tradition of mumming or mummering. This is where a group of people will don disguises and visit house to house, singing and performing and asking the inhabitants to guess their identities. This tradition also bears similarities to house-visiting wassailing traditions, in particular the Welsh tradition of the Mari Lwyd, where a horse’s skull, decorated with ribbons and flowers and covered in a sheet, (that being Mari herself) is paraded from house to house, asking entry, and being denied or granted entry, all in the form of song. Mumming and wassailing have evolved today into the tradition of carol singing from house to house, although some mumming and wassailing traditions survive in their own right – including Mari Lwyd.

The ancient festival of Yule also has clear connections with Christmas, with the word still being associated with Christmas in the English language, and also being the root of the word for ‘Christmas’ in many other languages. Yule was originally connected to the Wild Hunt, the god Odin, and the pagan festival of Modranicht.

Yule still lends its names to traditions such as the yule log and the yule goat. The yule log is a tradition featuring a log, or in the past even a whole tree, being burnt in the home during the festive period, often saving a part of the log either to light next year’s log or to keep beneath the bed for good luck.

The yule goat is a traditional gift-giver in some Scandinavian countries, with the Finnish word for Father Christmas ‘Joulopukki’ literally translating to ‘yule goat’. The yule goat would have originally been a goat-man who delivered presents in the place of any Father Christmas figure, the role often played by an uncle or family friend in a goat mask. However, the yule goat was also a character in some wassailing traditions, in which instance he would usually be demanding gifts rather than giving them.

The yule goat may also refer to a goat figurine, usually made of straw, that is used as a decoration throughout Scandinavia and Northern Europe. The goat is thought to originate from the goats who were believed to pull the chariot of the Norse god Thor. One of the more famous yule goats is the Gävle Goat in Gävle, Sweden, a several metres-tall straw goat which has repeatedly been the subject of arson attacks since its first display in 1966.

The goat went four years without burning between 2017 and 2020, the longest it’s ever been without being destroyed. In an almost comically pagan turn of events, some people view this to have brought bad luck, given the state of the last four years, but thankfully, this year’s goat was successfully targeted, and ceremoniously burnt (as an offering?).

The theme of sacrifice is also linked to some of our traditional Christmas plants, with mistletoe even being linked to human sacrifice and fertility rituals. Holly, traditional evergreens, and even the Christmas tree itself have long pre-Christian traditions, which you can read more about here.

0 Comments