At a first glance, the prank-centric TV show/film series/daredevil collective Jackass might not seem like something that would become queer cultural. Yet somehow, it sort of did.

I got into Jackass when I was around 20, having just completed my first year at art school and with a long summer ahead of me. I was getting into ’80s hair metal for the first time, drinking more beer than usual, and shrugging off a period of feeling more femme and returning to my messy masc roots. When I saw Jackass for the first time, its cast drunk and masochistic, dishevelled and just slightly homoerotic, I felt some kind of kinship with them.

I started wanting to emulate them more and more, trying to dress like Johnny Knoxville or Bam Margera, listening to CKY and Mötley Crüe, and at one point cutting off a lock of my hair, leaving me with a bald patch at the back of my head, in an homage to one of their pranks. The lock of hair then hung on the living room wall for the next two years like some kind of trophy of my masculinity, though why it meant that exactly I couldn’t at that time fully explain.

Johnny Knoxville in 2011, photo from Gage Skidmore

Johnny Knoxville in 2011, photo from Gage Skidmore

Throughout much of my life, especially since coming to realise my own transmasculinity, I’ve tried to emulate men or masculinity, either in look or in behaviour. Sometimes, it’s left me feeling depressed and alienated – and dysphoric – like when, as a stocky 14-year-old, I desperately wanted to look like gaunt Suede frontman Brett Anderson.

But sometimes it’s genuinely affirming – Jackass being one of those instances. For some reason, their masculinity affirmed my own, made me feel included, one of the boys. The masculinity that they seemed to present was accessible to me, both as a person who’d been raised female and as a queer person.

I also started noticing a particular interest in Jackass amongst my queer friends and queer people I know, some of whom were having their ‘Jackass phase’ along with me, and some who’d already been into the show for a long time. It made me think there must be some genuine connection between queer masculine people and Jackass, and so I decided to explore the subject, both to work out why exactly I felt this connection to it and if my reasons were akin to other queer Jackass fans’ reasons.

Thank you to the people who have contributed to this piece, allowing me to attempt this exploration into Jackass, its connections with the queer community, and masculinity.

So, what is queer masculinity?

There is no easy answer to this. The definition is subjective, and for some, indefinable – as is the definition of masculinity in itself. Personally, I could define queer masculinity best as a more realised, stylised, nuanced, and aware version of whatever cis and heterosexual masculinity is, including much of the same markers but performed knowingly, compassionately, and sometimes even satirically. But that’s only my definition today, ask me tomorrow and I could define it completely differently.

This indefinability is something that failed writer (their words, not mine) Lillian expressed as well. “It’s definitely something I relate to, yet I find it difficult to describe. Maybe because I find it difficult to even define masculinity. But then, I think what queer masculinity means to me is somehow divorced from masculinity. It’s not how I feel about masculinity, it’s just how I feel”, he said.

Jamie also said that he felt unable to describe it, but felt it tied to his sexuality more so, saying: “Oftentimes I feel that my gender is more tied to my sexual orientation and sexuality than, like, a separate thing”. In attempting to define it further, he added that to him, “queer masculinity is deviantly soft hardness and hard softness. Amorphously rigid, velvet on brick, soft skin with a tight grip. It’s sweat, it’s roughness, it’s broken teeth, it’s mascara, it’s pearls, it’s sticky syrup, it’s all of this smeared together.

I think it’s jumping off shit and having blood and dirt on your hands, hands which reach out and grab another man’s face to kiss him hard.”

Animator Kel and student Eric both described queer masculinity from the perspective of being trans men, and how they both feel this has allowed them to deconstruct cis masculinity. Kel said: “my sense of masculinity has been informed by being raised and socialised up to a certain age as a girl. Having a different perspective and experience of adolescence I feel like I’m able to deconstruct cis-masculinity in a way, and bring the elements that I want to being a man.”

Eric expressed something similar, saying that to him, “as a transman, queer masculinity is a way of exploring masculinity without the toxicity I think cis men often experience with it. I relate to it more than I do cishet masculinity in some ways, because it has further room for playing with the masculine role than in the strict idea it has been for a cis straight man.”

Freelance painter and medical illustrator Nicholas also described this sense of being able to critique masculinity whilst performing it:

“I feel Queer masculinity is engaging in the performance of gender in a way that is palpably different or subversive, despite the surface level appearance. It’s something I can definitely relate to as very cis masc presenting, and the feeling of ‘no not like that’ when present in a heteronormative male space.”

But what about the masculinity depicted in Jackass and by its cast?

Jamie described it simply as “homoerotically heterosexual” – “Honestly, I don’t think I can do any better than that!”, he said. Kel expressed that he felt there was a warmth to it, saying: “I see it as, what are to me, some of the most positive elements of masculinity: camaraderie, solidarity and loyalty to each other. Celebrating the gross and silly elements of masculinity by [being] vulnerable with each other which is nice.”

Lillian noted the performativity of the masculinity portrayed in Jackass, describing it as “performatively over-the-top, yet strangely authentic. Almost as if the performance of masculinity is put on, yet that put-on comes natural to the cast.” Nicholas also noted a sense of self-awareness or critique to the way that their masculinity is performed, saying “I feel like it’s self-deprecating masculinity in a way that masculinity finds damaging and undermining. Like revelling in your own weakness and pain, but for a laugh. That's something that the veneer of masculine power cannot stand.”

Eric also drew focus to the pain that the cast put themselves through and how that ties into their masculinity. “I think it kind of depends on which one of them does the stunt, and what stunt it is. For the most part I think it is the kind of dumb, irrational showing off the extremes of what you can do with your body.” Bam Margera in 2013, photo from Bam.Monzón

Bam Margera in 2013, photo from Bam.Monzón

“Taking it like a man”

People have often drawn focus to the tolerance of pain and the idea of “taking it like a man” as perceived parts of masculinity, and also how this relates to Jackass. Emily Chivers Yochim in her book Skate Life: Re-Imagining White Masculinity discusses Jackass and masculinity, and quotes David Savran and his discussion of what “taking it like a man” might mean. (Chivers Yochim’s writing about Jackass is worth reading as a much more critical alternative to this piece, providing further analysis of masculinity in Jackass and exploring how the cast’s whiteness interacts with their deconstruction of masculinity.)

Savran suggests that the phrase “taking it like a man” seems “tacitly to acknowledge that masculinity is a function not of social or cultural mastery but of the act of being subjected, abused, even tortured. It implies that masculinity is not an achieved state but a process, a trial through which one passes. But at the same time, this phrase ironically suggests the precariousness and fragility—even, perhaps, the femininity—of a gender identity that must be fought for again and again and again. For finally, when one takes it like a man, what is “it” that one takes? And why does the act of taking “it” seem to make it impossible for the one doing the taking, whoever that might be, to be a man? . . . Why can the one doing the taking only take it like a man?”

This could be read as applicable to queer masculinity too, some queer masculine people indeed having to fight to prove their masculinity to themselves or to others in a culture that can have definitions of masculinity so rigid and inaccessible – whether you’re queer or not. However, in some ways Savran’s quote applies more to cis or heterosexual masculinity, to hegemonic masculinity, or more specifically, to people who may not realise the inherent performativity or fragility involved in “taking it like a man”.

In this way, Jackass and queer masculinity are once more tied – the knowledge of performativity expressed by queer masculine people is present in Jackass. Its cast seem to often mock each other and themselves with the idea that they should be taking their pranks “like a man”. By using the concept as a recurring joke, they repeatedly highlight the ridiculousness of it, and through the context of the camera trained on them, its performativity.

When I asked the people participating in this piece what the phrase “taking it like a man” meant to them, the idea of stoicism or self-censoring, perhaps even to the point of toxicity, came up often. In this way again, Jackass defies the idea of “taking it like a man”, its cast reacting with however much fear or ridicule they feel like to each situation. Even when they react with bravado, it is done with enough humour and exaggeration to make it clear that they are mocking that mode of typical masculine “tolerance”.

In reacting this way, they also draw attention to the fact that the situations they are suffering through are self-inflicted – just as the stoicism of “taking it like a man” is. And as Steve-O once knowingly said: “Why is it the things that make you a man tend to be such dumb things to do?”

Jackass: transgressive or hegemonic?

If the cast of Jackass are so seemingly self-aware of the construction and performativity of masculinity, it then bears asking: is Jackass some in-depth transgressive deconstruction of hegemonic masculinity? Or just a bunch of sarky idiotic daredevils?

I asked the participants for this piece if they felt that Jackass transgressed or reinforced traditional or conservative ideas of masculinity. Lillian said she felt that it was a bit of both. “It transgresses in how it paints masculinity as inherently performative, and in its occasional tenderness, but then I suppose its aesthetics, at the very least, reinforces that ‘boys will be boys’ mentality”.

Eric also identified this, saying, “I think absolutely both. I feel like in the early 2000s it perpetuated a stereotype of men as being irrational and stupid and unable to control themselves, not giving them the consequences they should get, which I’d say is a traditionally masculine stereotype. But it is also a very freeing way of looking at masculinity, as not really thinking and just doing, and does take away that idea of ‘The Man’ as a money-maker for a family having to uphold a certain look, rather just let people jump around and have fun. It also helps that they are not all the beauty standard of masculinity, but rather just a mix of loads of different guys who want to have fun.”

Kel and Nicholas both felt it transgressed more than reinforced, Nicholas saying that it “depends on the sketch, but broadly I think it is transgressive, in that many of the stunts would be seen as hazing if it wasn’t done on an even playing field.” Kel said: “I see it as another deconstruction of traditional masculinity, mocking it in lots of ways, doing dumb embarrassing stuff with a complete lack of the shame that would normally be associated with a man doing these things.

“It’s cool how all the bits about their dicks are never about how big their dicks are, they just smash the fuck out of them anyway! At the same time they do also exhibit some more traditional masculine traits like bravery, courage, strength etc. But I feel like that gets overshadowed by all the nonsense.”

Jamie also noted a transgressive-ness, saying: “I think in a lot of ways though Jackass does transgress conservative masculinity, especially for the early 2000s and its particular defensive and guarded heterosexuality. They’re naked a lot and it’s very homoerotic, but they’re so confident and secure in their masculinity and their sexuality. They’re sexual with each other in the way friends are sometimes.”

However, he also brought up Bam Margera specifically, and the ways in which he reinforces traditional masculinity more so than the rest of the cast. “I feel that his masculinity is much more traditional than the others. Despite things like painting his nails sometimes and some of his more emo-influenced fashion, he comes off as aggressive and mean. His pranks tend to be at others’ expense in a less jovial way; the other person is hurt or humiliated and Bam sits unaffected and blameless. To me he embodies the ‘It’s just a joke, dude’ type guy who says or does something hurtful then gets pissed off when he’s asked to stop”, he said.

Fragile “alpha male”, Bam Margera

Many people’s least favourite Jackass crew member and in many ways the one who most adheres to hegemonic masculinity, Bam Margera is an interesting case to consider. Chivers Yochim describes Bam as “the ultimate alpha male and the leader of the multiple male minions who took part in producing the CKY skateboarding videos, Bam routinely performs the superiority of white adolescent males over women, people of color, adults, and even his other white male friends.”

However, there are still some ways in which Bam does not fit into traditional masculinity, and one might wonder if this is what drives his incessant “alpha male” performance (because it is, most definitely, a performance). As Jamie pointed out, Bam’s painted nails and emo-adjacent fashion could set him apart from his fellow crew members, and perhaps as more traditionally feminine or more traditionally queer.

Those who grew up with early ’00s nu-goth might also remember Bam’s obsession with Finnish “love metal” band HIM and subsequent tumultuous friendship with the band’s pretty boy singer Ville Valo. A Jackass themed episode of MTV Cribs revealed that the bed that Bam shared with his then-girlfriend Jenn Rivell lay under not one, but two HIM posters – one of the whole band looking down on the bed from above the headboard, and on the wall facing Bam’s side of the bed, a poster of the cover of the band’s second album Razorblade Romance, which features Ville posing alone against a vivid pink background, shirtless and with a full face of makeup. Bam Margera's HIM-themed bedroom / YouTube

Bam Margera's HIM-themed bedroom / YouTube

It was seeing this that made Bam more endearing, or at least more sympathetic to me. Whether Bam was overtly or only subconsciously aware of the potential for his interests to be perceived as queer or feminine, it could explain his repeated efforts to position himself as the “alpha male” in an attempt to counteract his less traditionally masculine traits.

Although Jackass in many ways works thanks to the obvious tenderness and care that the crew feel for each other, that care is rarely overt, instead wrapped up in layers of sarcasm and irreverence, as with everything the cast does. There is an element of unflappable indifference to the way they conduct themselves, which in many ways is what allows them to play with masculinity the way that they do.

In some ways, Bam lacks this air of nonchalance, and is in a much more vulnerable and open position than the rest of the cast. His family, friends, and girlfriends appear on screen – unlike the rest of the cast who maintain a sense of distance between the show and their personal lives. His interest in HIM also makes him more vulnerable, his obvious passion for them and their music at odds with the laidback irreverence usually associated with Jackass.

The problems with Jackass and non-queer masculinity

It’s worth noting that this irreverence in Jackass is as much a performance as the events they are feigning indifference to. This then leads us to a potential divergence between queer masculinity and the masculinity in Jackass. While queer masculinity is happy to set itself at odds to hegemonic masculinity for a variety of reasons, in Skate Life… Chivers Yochim argues that Jackass sets itself at odds simply for its cast to gain a kind of personal power over hegemonic masculinity.

She argues that the way in which the Jackass crew conducts themselves allows them to “demonstrate their knowledge of masculinity as construction while suggesting that they are above such display”, more specifically that their irreverence for hegemonic masculinity “rests on and reconstructs a new mode of masculine dominance in which men can demonstrate their confidence and power by suggesting that they are “man enough” to ridicule dominant norms of manhood”.

She also notes that “masculinity must shift forms in order to remain powerful”. We can potentially see an example of this in the idea of the “soft boy”, that describes an identity adopted by masculine people, usually cis het men, who do not match up to hegemonic masculinity to still retain a sense of power or control, usually over women, via emotional manipulation rather than physical strength.

It’s worth considering then that although Jackass deconstructs hegemonic masculinity and although the queer community has found affirmation in this deconstruction, the Jackass cast themselves are at the end of the day still reportedly cis heterosexual men and therefore still interact with masculinity through that lens.

Non-queer masculinity, whether hegemonic or not, often sees itself in a ranking system (the recent focus on ideas of ‘“alpha”, “sigma”, “beta”, etc. males’ being a particularly annoying example), at risk from other forms of masculinity or from femininity. Queer masculinity is often about gender expression for the sake of celebration rather than combat, not characterised by being at risk from or opposing other forms of expression. As long as someone is viewing masculinity as a mode of domination or as something at risk of subjugation, then the way they perform it will always be on the verge of toxicity – no matter their irreverence.

This leads me back to Chivers Yochim’s quote that “masculinity must shift forms to remain powerful”. While in some ways she is right, I feel the idea could be improved by specification, as its current wording feeds into the idea of masculinity as a thing that must either dominate or be subjugated. Masculinity is not inherently bad or constantly seeking dominance. Hegemonic masculinity maybe, cis or heterosexual masculinity maybe, but masculinity in itself is too wide and personal and vague.

If there’s one main thing I’ve learnt from queer masculinity and even from Jackass it’s that I can love masculinity. It’s not an evil insidious force that has power over all other forms of gender expression. People can wield it as such but hey, people also use femininity in that way too. Gender equality isn’t achieved by destroying masculinity, but by transforming it.

We don’t know the Jackass cast’s personal motivations for the way that they perform masculinity and whether or not they see it in terms of subjugation vs. domination. Whatever their perceptions are, their presentation of masculinity has still been an important reference point for the queer experience of celebrating and transforming masculinity.

I must note however, that it is for most just that – a reference point. Although we as queer people can enjoy the show and can even like and respect the cast, this does not necessarily mean we are holding them up as the pinnacle of how masculinity is and should be performed and do not seek to absolve the cast of any of their less positive actions or comments.

Okay, but why do queer people like Jackass?

I personally feel that there was an openness to the camaraderie between its cast members that felt accessible, and that accessibility didn’t rely on being a cis het man. I also feel that the way they relate to each other is very much male, but not traditionally or hegemonically male, again making it relatable to me as a queer masculine person and the way that I interact with my queer masculine friends.

Also, as a person raised female, I’ve always felt like I had an unexpressed male adolescence, never necessarily having had all the experiences I wanted of doing silly or reckless things with my friends in that particular stupid teenage boy way. Jackass and its cast represented that world to me, but because of its accessibility I was able to live vicariously through them, and because they were grown men and not actual teenage boys, it didn’t feel infantilising to relate to them, only aspirational and affirming.

Eric and Kel both also identified a similar experience. Eric said: “Personally, I think it is because as someone who transitioned after my initial teenage years, I kind of romanticize the idea of being a dumb teenager who gets to do whatever. I think it is a way of behaving and stuff to do [sic] that have for a while been closed off for queer people, and then especially trans masculine people.”

Kel reiterated this feeling, saying: “I think the element of juvenileness draws a lot of queer masculine people to it because it’s a way to experience something they may have missed growing up, the idea of being a silly little boy cutting about and making a mess is something I never got to experience, so watching grown men do it and have such a good time feels kind of liberating.”

Lillian instead pointed to their childhood as the time when they were interacting with and relating to Jackass, noting that “Jackass was a cultural phenomenon during a very transformative age, and in a lot of cases the first time we either felt a complete disconnect, or camaraderie, with our masculine peers,” but also saying that “as a kid I found it somehow off-putting for its crassness, but also oddly endearing in its occasional tenderness and almost aspirational in just how much genuine fun the cast seemed to be having. My friends and I definitely emulated their stunts in the schoolyard.”

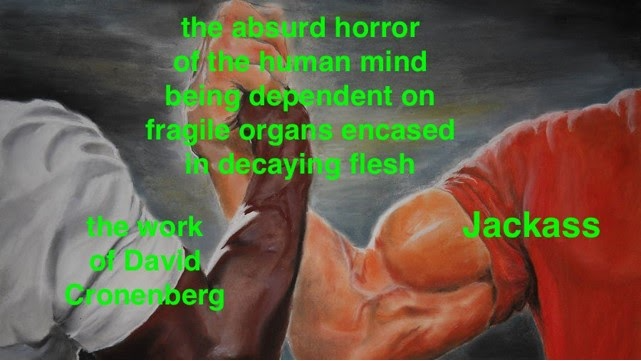

Kel brought up something interesting, describing how he felt that Jackass also echoed his experiences of medically transitioning, and also drew comparisons to body horror such as David Cronenberg’s films. “This is maybe a bit more niche but I also think of this meme a lot in relation to medically transitioning and Jackass and body horror,” he said (image below).

Original artist unknown

Original artist unknown

“The idea of physically destroying the form to create something new is interesting to me! Being on hormones means I’m also familiar with self-inflicted weird and exciting things happening to my body (maybe hormone therapy is very Jackass of me).

“And the Jackass boys love displaying bits of broken bone and flesh to the camera in the same way Cronenberg does which is cool!”

Jamie also spoke about the stunts they perform, along with the camaraderie and care they display afterwards. “You get the dumb part of being a man where you break your nose doing something absolutely brainless, and the sweet part of being a man where you just really love your buddies. The brotherly love in Jackass is so present and tender, but wholly male,” he said. “Maybe it’s because it’s an accessible and open masculinity: they’re physically straining and hurting themselves but they also tell one another that they care deeply.”

Nicholas highlighted that Jackass’s accessibility is what they feel draws the queer community to it. “I think there is an air of acceptance and matter-of-fact-ness about the entire thing, as if to say 'we are all getting slapped with a fish, and you’ll get slapped by the very same fish.' Some aspect of not fixating and making a big deal about who you are, as long as you’re taking part”.

Does anyone want to be in my queer Jackass knockoff TV show?

To conclude all this, I love Jackass and I’m glad it was a comfort to me and to my queer friends, and I am glad that it was a mainstream piece of media that was playing with and subverting hegemonic forms of masculinity. However, it also sort of disappoints me that it had to be Jackass, in all its essential supposed cis-ness and heterosexuality and with its several faults, and that there were no or very few queer masculine alternatives that I could bond with this much instead.

There are queer masculine pieces of media that I also love and relate to but there aren’t enough. Trans masculinity especially is so under represented in the media. Even now that there is more trans representation in media, it skews more often to depictions of trans women (who are often played by cis men which is why I think the representation skews that way – not for the sake of championing trans women, but rather to give cis actors the chance to give a so-called “brave” portrayal and win a little award at the sake of actual trans women’s public image and safety, but don’t get me started on that…).

Jackass played an important and invaluable role in many queer masculine people’s lives, but now it would be fitting to see opportunities for queer people’s masculinity to also be affirmed through actual queer masculine people. Despite the Jackass crew’s acceptance of and celebration of queer culture, their trademark irreverence also means that they have made missteps in their handling of it.

For instance, Steve-O’s statement in Vanity Fair that, “We always thought it was funny to force a heterosexual MTV generation to deal with all of our thongs and homoerotic humor. In many ways, all our gay humor has been a humanitarian attack against homophobia. We’ve been trying to rid the world of homophobia for years, and I think gay people really dig it too.”

Despite the definite well meaning behind this, it still reveals that homosexuality is somewhat of a joke to him, or a concept to play with, rather than a lived reality. Queer culture and queer masculinity do not necessarily have to be played straight (pardon the pun); there can be humour and irreverence in them too, but that humour stings less – and to be honest lands better – when it’s coming from someone who’s lived it.

It’s not only the queer masculine community that would benefit from more queer masculine representation; if they’re open minded to it, non-queer masculine people could benefit from it too. As I said before, masculinity is not inherently bad, and equality comes from transforming masculinity, not destroying it. The more representations there are of non-hegemonic masculinity, the better we can understand that masculinity is a varied and fluid experience, and from there (I hope) interrogate the endlessly damaging presumption that masculinity must always be in power or is at risk of losing power.

When I initially asked the participants for this piece what they liked about Jackass, Kel simply said: “I too, love to be silly with my friends!”

I think that at its best, masculinity, like Jackass, is sometimes just about being silly with your friends. And maybe a bit gay.

0 Comments