Why do we have punishments in school? Do they work? How are they linked with our flawed criminal justice system? Before we jump into these questions, I’m going to look at how punishments in schools are actively harming and discriminating against certain groups of young people. At best, this means putting them on a path for a less successful life, at worst, channeling into the school-to-prison pipeline. Later, I’ll go through exactly what these terms mean and the statistics, but, so as to not bury the lede, I think that severe punishments don’t teach alternative behaviour: they just harm students. Schools are supposedly meant to educate young people but these punishments inhibit learning and don’t teach them anything.

The question is: are punished students failing school, or is school failing them?

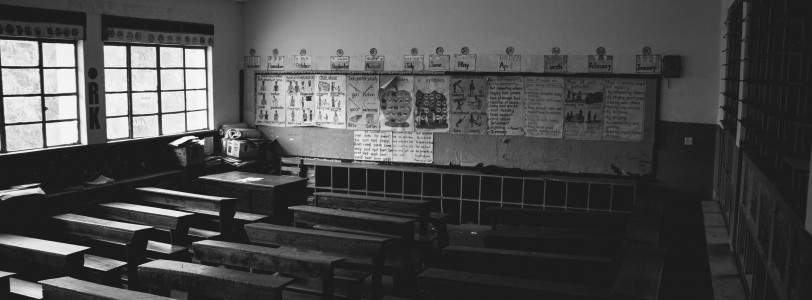

Punishments: past and present

Let’s first examine the history of punishment in British schools.

One psychological definition of punishment is anything that decreases the occurrence of a behavior; physical pain, withdraw of attention, loss of tangibles or activities, a reprimand or even something others would find rewarding, but the particular individual does not like (Lefton, 2002; Kosslyn & Rosenberg, 2002). Punishments have always been used in schooling as one the most important tools to control student’s behaviour and to enforce discipline, although legislation has resulted in changes to how that punishment is enacted.

Corporal punishment, which includes any physical punishment like caning, or beating was outlawed by the British Parliament in 1986, after a ruling by the European Court of Human Rights. Punishments until then included the use of weapons like bamboo canes, rulers, and even slippers before legislation came into place. In Scottish schools, a leather strap with tails, called a tawse was used as a punishment. The European Court ruling said that such a punishment couldn’t happen without parental consent, and that a child's ‘right to education’ could not be infringed by suspending children who, with parental approval, refused to submit to corporal punishment.

The UN Convention on the Right of the Child (signed in 1989) recognizes that corporal punishment employed by teachers and parents in schools and homes seems to be ineffective, dangerous, and an unacceptable method of discipline that brings negative rather than positive impacts to learners.

So, the severest punishments previously employed were a violation of the fundamental rights to the child as it may cause pain, injury, humiliation, anxiety and anger that could have long term psychological effects (TEN/MET, 2008).

Nowadays, punishments or ‘sanctions’ could involve a telling-off, a letter home, removal from a class or group, or confiscating something (e.g. mobile phone). More stringent punishments include detention, isolation, suspension and finally expulsion. These punishments vary from school to school and are mostly self-explanatory. Isolations are particularly brutal punishments, with students being kept alone or in ‘isolation booths’ for extended periods of time, are told to be completely silent and are escorted to toilets. According to a 2018 BBC investigation, more than 200 pupils spent at least five straight days in isolation booths in schools in England.

These punishments are usually supported through the use of a so-called ‘zero tolerance’ policy. The policies are usually promoted as preventing drug abuse, violence, and gang activity in schools. Anyone in these schools who has a banned item or performs any prohibited action are automatically punished in a pre-defined manner; school administrators cannot use their judgment to reduce punishments, or consider the circumstances or context around the situation. For example, zero tolerance to knives means that a craft knife, a butter knife and a switchblade would all be treated the same.

There’s also lots of proof that these methods of punishment have severe negative impacts on students. A study of schools across Australia and America found that suspensions predict a range of student outcomes, including crime, delinquency, and drug use. Excluded young people also have lower odds of a stable, happy and productive adult life. Suspensions also raise the serious questions: is the school system able to accommodate a neurodiversity of students. Students with disabilities or mental health difficulties are disproportionately represented in school exclusions and school suspensions. Research from the University of Exeter concluded that young people with mental health need support to avoid exclusion, which can be both cause and effect of their poor mental health.

Police in schools

Concerningly, there’s an increasing number of UK schools that have school-based police officers, which has numerous negative impacts on students' life and learning. In a report by the Home Affairs Committee, MPs said that schools in areas with a higher risk of youth violence should be given dedicated police officers. Met Police Commissioner Cressida Dick said that every school and further education college in London has been offered a ‘named officer’ and that the officers carried out ‘high visibility patrols’ and delivered sessions and bespoke workshops to pupils.

The police are an institution focussed on punitive justice, deterrence and negative repercussions. In school, they serve as intimidation tactics to scare students into good behaviour. While this is not dissimilar to other punishments used in schools, this should not enter an environment that is supposed to be dedicated to learning and development. The truth is that to young people who have experiences of over-policing, the police can be an extremely threatening presence. Their presence criminalises children and suggests the worst in students. I think these punishments will increase young people’s resentment of teachers and authority and increase their violence and rebellion.

The modern approach to teaching

Through police presence and zero-toleration policies, modern schools continue to reinforce ideas that penalise black and brown communities, with a report by the IPPR finding that exclusion disproportionately affects children of colour. You might have heard the phrase ‘school to prison pipeline’ – this is the idea that school rules unfairly target marginalised youth, leading to more exclusions and eventually pushing children towards the criminal justice system.

The current authoritarian approach to schooling is just a reflection of something that is systemic to our society as a whole. Guilt is assumed and actions are not met with rehabilitation but with retribution. This mentality runs from the value of punishment in our society as a whole, and when young people need the most help, they get thrown out from their normal environment, away from friends and denied the support they need.

Teachers are important in every student's development and play a huge role in either encouraging or discouraging students from learning. Their influence on young people is enormous. From experience, I can definitely say that some teachers have made me question and learn things – others have done nothing but make me hate a subject. Learning can’t happen without good relationships between teachers and students, where students learn from teachers and teachers learn from students. But these punishments undermine those relationships and break trust.

Worse, these punishments prime children to fall into the criminal justice system through the ‘school to prison pipeline’. This is the process where students are pushed out of schools into prison. An example of this ‘pipeline’ is being sent out, then getting detentions, which leads to isolation, then temporary and permanent exclusion. After this, the student will move through the Pupil Referral Unit, Young Offenders Institution and then finally prison and reoffending. Research suggests only one per cent of permanently excluded students go on to attain five good GCSEs. And not only are these students more likely to be unemployed: they are four times more likely to go to prison.

It’s also important to remember that schools don't exist in a vacuum. There are real and important connections to be made between the punishment we employ in schools and the systems of justice we apply to society at large. We've already talked about the school to prison pipeline – but this goes beyond that. The school system and its punishments are a manifestation of the broader issues present in how we enact justice.

The key thing to interrogate in these systems of punishment is purpose. What do we actually want the system in question to do? Is the point to re-educate the wrongdoer? Is it to protect the community from them? Or are we just satisfying our need to see bad deeds go punished?

We have to be honest with ourselves and ask what we actually want out of these systems before we make any changes to them. If we're honest we can usually tell the difference between punishments that have meaning and those which don't. Those which come from a place of love, and those which come from a place of exhaustion. The ones we learn from and the ones which just breed resentment.

If we actually want outcomes to change for the better, we need to lean away from the punitive and move into the recuperative. It might not feel as satisfying. It will take time and energy and patience, but if we want a better world then we have to do it. So schools are a great starting point – but they’re not the end.

The future of punishment in schools?

This is a massive problem in schools, but there are ways to break this cycle.

For a start, there should be more resources directed at addressing roots of the problems, or looking at rehabilitative practices such as restorative justice to keep young people in schools. There are also pushes to make the school environment less hostile; Manchester-based organisations Kids of Colour and the Northern Police Monitoring Project have recently launched their No Police in Schools campaign, and are trying to ‘decriminalise the classroom’. A young group of South Londoners started a campaign called ‘Education not Exclusion’ to try and raise awareness of the vicious cycles of imprisonment.

Like always, thinking critically about who benefits and is harmed by institutions is key to changing these places for the better. With the recent increased awareness of the problematic nature of criminal justice, we can start to hope that things will change in schools. It’s evident that exclusions are not the answer – let’s focus on inclusion instead.

0 Comments