The problematic Proms?

The Last Night of the Proms: potentially the most controversial classical concert in the world. The Proms have held that oft-cited lofty position of “one of the Great British Institutions” and, mostly, it earns that title each year with its range of concerts in multiple musical genres.

The Proms (or officially The Henry Wood Promenade Concerts) were formally founded in 1895 by Robert Newham with the dubious mission to educate the general public, to “create[d] a public for classical and modern music”. Blatant culturally elitist motives aside, what he created and what Henry Wood would continue to foster was a concert series that ran with low-cost tickets and an informal atmosphere that could open up classical music to the public, where previously the genre had been reserved for the upper and middle classes. Regardless of intent, The Proms became one of the first attempts to egalitarise classical music.

However, in recent years, and with changing cultural attitudes, one element of The Proms has been seen to be increasingly problematic: The Last Night. The Last Night of the Proms is by far the most popular prom, and tickets have to be balloted to prommers who have been to at least five of the other prom concerts (although obviously that has been a bit different this year). The first half of the concert can be a collection of all sorts of pieces but usually consists of a few smaller classical/romantic works, and one or two modern compositions, generally with at least one new commission by a British composer.

The problems arise in the second half, which is a fixed programme full of pieces that have become seen as particularly patriotic. The Last Night is by far the most raucous of The Proms concerts. Usually, it consists of audience members throwing balloons around the auditorium, letting off party poppers and honking air horns, and there is a bizarre tradition of bobbing up and down during Henry Woods’s “Fantasia on British Sea Songs”. Flag-waving is also a significant part of the second half, a matter that has been previously heavily politicised in the wake of the Brexit situation, with EU and European flags — previously flown to represent the breadth and diversity of The Proms’ audience — being flown by Remainers in protest, and Union flags being flown conversely by Brexiters.

The flag issue was almost certainly the biggest storm-raiser in previous years, but this year attention turned to the pieces. Some of them, including Jerusalem and Rule Britannia, are seen by many as glorifications of colonialism and a misplaced sense of patriotic pride. Objections to these pieces have been concentrated this year by the explosion of the Black Lives Matter movement, although the issue actually seemingly started from another big event. Coronavirus has meant that the Proms had to be drastically altered this year, with reduced performers on-stage and, most extremely, no audience.

However, what could very generously be described as misguided advice from the government said that singing would be even more problematic and, seemingly in response to this, the BBC issued a statement that these pieces would be performed without lyrics. Many — especially those who see the BBC as a Left-Wing-biased organisation — saw this as a thinly veiled political move to de-problematise the music, and complaints poured in. The BBC eventually walked this back, seemingly on the orders of the new director: Tim Davie. The U-turn then created a storm amongst the Left, who saw the move as the BBC cowing to pressure from the Right, and thus the songs became one of the hottest political topics in music.

A new vision of Jerusalem

Then on Saturday 12th September, the Last Night arrived, and a surprise was in store to many who hadn’t seen the digitally published programme: there would not only be a performance of Jerusalem in the concert, there would be two.

One of the new commissions for the first half turned out to be a reworking of Jerusalem composed by acclaimed composer Errollyn Wallen CBE. I was one of those surprised people since I hadn’t been paying much more than a passing attention to the Proms (although I did see the Baroque prom which I quite liked), but I happened to be watching on Saturday when I heard this new version of Sir Hubert Parry’s famous hymn. My immediate reaction?

“I can’t wait to see what Twitter has to say about this.”

Twitter did not disappoint. The #proms tag blew up with comments on the piece. There were a few clever insults made at the new piece’s expense, and a lot of not very clever insults. Amongst that was a smattering of people spamming the #defundthebbc hashtag and an equal number hitting back against the “gammons” who disliked the radical arrangement. There was a splash of people defending the work too, but only a handful. All in all, it was sorta like a social media Jackson Pollock.

The longer I watched the tweets stream in I started noticing a few patterns. Initially, I was going to write this based loosely on those impressions, but then I decided that this would be a good opportunity to dust off my programming skills…

API in the Sky

Luckily for me, Twitter has an API — a system by which approved programmers can create code to communicate with Twitter to get data. In this case, I created a bit of code that asked to get the information of every tweet that had the tag #proms or #lastnight of the proms. Then it dumped that information into a CSV database that I could then open up and mess with in Apple Numbers. With a little bit of tweaking, the code ran. 55.82 seconds later the code had imported 847 tweets.

search_terms = ['#proms', '#lastnightoftheproms']

for term in search_terms:

for tweet in get_tweets(term):

if tweet not in tweet_list:

writer.writerow(tweet)

tweet_list.append(tweet)

Opening the CSV file, it became immediately obvious that not all of these results were going to be helpful to me. A lot of them were bots or advertising accounts misappropriating the #proms tags to help gain viewership by piggybacking off of relevant topics. A lot were talking about other pieces or different proms entirely. So I created a filter to look for the tag #Jerusalem or just mention of the word “Jerusalem” within the table. Exactly 150 results. That’s more manageable. Now I could start evaluating and drawing some conclusions about the general opinion of Twitter on this issue.

Of course, this is far from an ideal way of gauging this information; comments on other tweets are replies and don’t tend to reference directly the subject the original tweet was about, or include the hashtags, which excludes it from the search, so I will have lost a number of tweets there. However, I wanted to keep it to direct references only because — as soon became evident when going through this — context is critical; anything more ambiguous than what I had already got would require too many value judgements on my part and I didn’t want to bias the data any more than was inevitable. Even then, some tweets were ambiguous, mostly because I had to check whether or not some were being sarcastic!

When it wasn’t immediately apparent what the tweet meant out of context, I followed the URL of the tweet to check if it was part of a chain of tweets that explained it or explicitly stated the opinion before putting down the response in the table. What I didn’t want to do was Twitter-stalk a bunch of strangers, or make assumptions about their views based on other tweets not related to this particular event, so if checking the tweet URL didn’t work, I’d stop looking and just mark the tweet as unclear.

I evaluated the tweets on four basic principles. Whether or not they seemed to — on a basic level — like the arrangement, whether the tweet expressed a political opinion relating to the performance of this arrangement, if so whether or not that opinion was positive or negative, and whether or not they expressed whether they like or disliked the prom as a whole.

I sit and stare at spreadsheets for a few hours

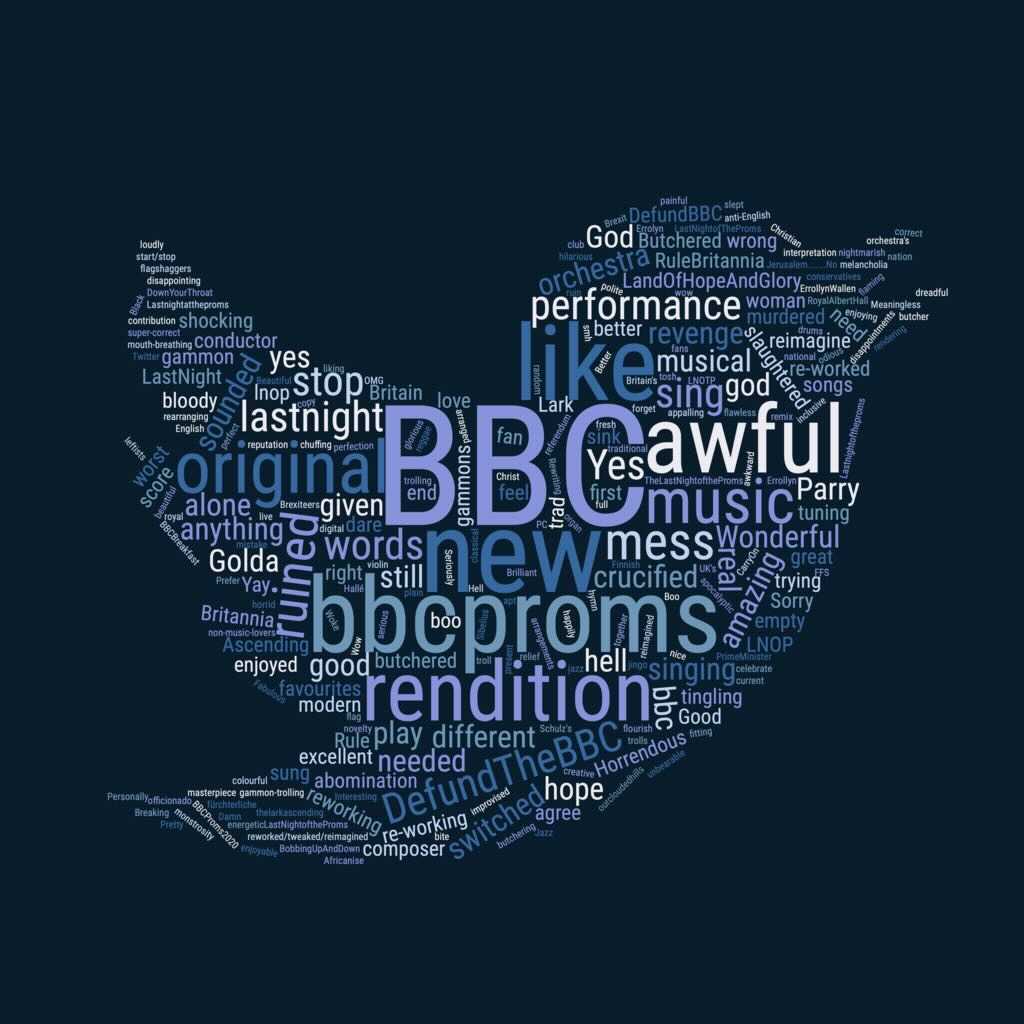

Word-cloud of the data gathered from Twitter. The larger the word in the cloud, the more frequency it appeared in the tweets with.

Word-cloud of the data gathered from Twitter. The larger the word in the cloud, the more frequency it appeared in the tweets with.

So, the overall impression of Twitter certainly seemed to be that musically they really didn’t like Warren’s arrangement. Of the 150 results, 104 tweets showed a clear distaste for the new arrangement. This isn’t exactly surprising, as people are far more likely to go to social media to complain about something than praise it — an idea that can be observed simply by seeing the number of drives being made to “reclaim” social media to be a positive space. I also was entirely expecting it from a musical perspective; the piece was highly dissonant and structurally bizarre, both of which are unlikely to be accepted by the general proms-watching public. I remember the National Youth Orchestra receiving a similar reception on social media after a more avant-garde performance a few years ago.

The sheer strength of feeling of the criticism was also very evident. A few tweets went with descriptors for the piece like “massacre”, “butchered”, “an assault on the eardrums”. There also seemed to be a sense that people thought the new arrangement was insulting to Parry’s original work; claiming that it was “messing around with” the piece. One even claimed to be a distant relative of Parry who saw the performance to be simply “cringe”.

There were also a number of people who gave somewhat more specific criticism. One claimed the issue was in adding “melancholia” to an uplifting piece of music, another describing it as “muddled” and “meaningless”. Overall, it seems to be the tone of the rearrangement that has got the goat of a lot of detractors.

A few tweets mention a rumour that Wallen didn’t even know the words to Jerusalem before writing the piece, but according to this interview with the composer she describes how the words have a very personal meaning to her that she considered while writing the music, so I think we can chalk that one up to gossip and rumour.

Of the 150 tweets, only 12 seemed to express a clear, unambiguous liking of the piece. Positive descriptions referred to the piece repeatedly as “colourful” and “energetic”. Opinions amongst the appreciators seemed split on the original piece, with a few seeing the old version as “odious” and that the piece was a clear improvement, but others seeing it as a separate entity that could be appreciated in its own right without impinging on the status of the original, with some even saying in their tweet that they were looking forward to the original rendition later on in the programme.

What struck me as interesting was the attitudes of people regarding the perceived socio-political elements. As mentioned earlier, there was a sizeable chunk of people who saw the original BBC decision to not sing the lyrics to some of the patriotic songs as a political one: a petition to “save” Rule Britannia and Land of Hope and Glory raised 79,487 signatures in under two weeks (contrast that with an ongoing petition to remove Rule Britannia from the programme which has of the time of writing only garnered 1099). It was inevitable then that this arrangement would also be taken as some sort of political agenda on the BBC’s part, visible in tweets mentioning “the #BBC revenge” and “a rehashing of Jerusalem […] is jangled out for the woke”. But not everyone showed a dislike for this being a potentially political move.

The data showed a total of 34 people who referenced some kind of political involvement to the piece itself. Of these, five tweets were ambiguous to whether or not they liked or disliked the idea of there being a political element to it and two pertained to other political matters (one who thought it was an example of English bias against the rest of the Union and another who thought it should be included but that much of the rest of the Last Night’s programme from “a past we should forget” should be removed). This left a perfect 50/50 split between 14 people who approved of the idea of this being a conscious political choice on the BBC’s part and 14 people who disapproved.

The data shows that those who disliked the idea of this being a political choice also unilaterally disliked the piece itself. So far so expected. The response from the people who liked the idea was more mixed however. One person openly disliked the piece but liked the negative response it was getting from certain people:

Sounded awful but I’m loving the jingo meltdown

Three others openly expressed a positive opinion towards the piece. One thought it was a positive expression of nationalism and hope for a future as a nation despite other political issues (this person was clearly neither fond of Brexit nor the current government). Another thought the piece embraced inclusivity and progressivism, something that I imagine the composer would be cheered by.

However, the third person shared a lot in common with the remaining group of 10, all of whom’s exact opinions about the music itself were unclear (their general opinions may have been given away by the rest of their profile but as I said earlier, I’m attempting to evaluate the data as it stands without too many assumptions about a person’s personal views external to the tweets). Like the person who openly disliked the piece, these people all appeared to see the new arrangement of Jerusalem as an elaborate troll by the BBC, with many referring to it in exactly those terms.

Many of these tweets don’t express a personal opinion on the musical qualities of the piece, simply that they were glad that it annoyed a certain demographic of people. This is where we see a prevalence of a particular slur that pops up in this data. There was a selection of (often very creative and colourful) derogatory terms for people who are left or right politically aligned throughout these tweets — it’s Twitter: no surprises there — but one popped up more than any other: “gammon”. To the people who liked the idea of the piece being a troll, this word popped up frequently to describe a particular type of prom-watcher.

Emerging from the Rabbit-hole

So, what can we take away from this? Well, if you put aside the many limitations of this analysis and the fairly small sample size available, a few things.

At a basic level:

Over two-thirds of the Twitter users disliked the new arrangement of Jerusalem. Only 12 people in the sample (8.3%) showed a clear liking for it musically.

Just over 22% of people expressed some belief that the new piece was part of some kind of political decision on the BBC/Proms’ part.

People seem evenly split about whether this is a good or bad thing.

63% presented a clear positive or negative opinion of the music without expressing any political opinion as part of their comment.

Three people showed open disdain for the prom as a whole (2%), as opposed to 10 people (6.6%) who openly praised it. Only one person in the sample gave a truly mixed opinion with positive and negative elements.

The pejorative “gammon” appeared 10 times amongst these tweets, alongside a general backdrop of name-calling from both sides of the political divide.

What broadly I think this data points to though is two messages: one worrying and one hopeful.

It points to a pervasiveness of an us/them left/right divide amongst the public’s perception of politics and its effects on the real world. What started ostensibly as a coronavirus measure was immediately picked up as having political motivations, and whether or not that is true the idea that nearly 80,000 people also saw it that way and felt strongly enough to sign a petition speaks volumes. Then in this data, we see the battle between the two sides of a left-wing body that believes that this piece is a step forward for the proms and a right-wing body that sees it as pandering. We see insults slung at invisible opponents, at an idea of what a proms-listener is.

What we also see is a majority percentage of people who are able to express an opinion about a piece of art without bringing politics into it. Not to say that music is/n’t, or even should/n’t be political, but simply that a majority group of people can criticise and praise a piece of work beyond its socio-political associations, even if the criticism is rarely constructive. It points to a social media that isn’t all Brexit and Trump and why the Left/Right are ruining everything, one that can acknowledge that appreciation or disliking of something can exist beyond politics. That is a surprisingly reassuring thing to take away from a long scroll through Twitter.

"People leaving the BBC Proms at the Royal Albert Hall" by p_a_h is licensed under CC BY 2.0

0 Comments