This session was first planned as a hand-on walk through of the different software Eric Braman and Olive DelSol used to engage children across Lane County, Oregon. However, after a quick introduction session the charming duo decided to run two splinter sessions: one to go through the hands-on, and one for those who wanted to talk more about the process and experience. I opted for the latter, which was run by Eric.

Talking about the Lane Arts Council’s in-school digital storytelling initiative, it was very clear just how important youth empowerment was to Eric. This wasn’t just something run because it sounded good on paper, but is a real opportunity to encourage young people to make their voices heard. This was something considered even down to the software used. Although the young people were given iPads to work with, all the apps were either low cost or free because they wanted to make sure that young people were able to carry on doing it after the sessions. This was to be considered as a starting point to a wider journey, not a one-off event.

Going into schools, the team invite students to tell their own stories, often working with poetry classes. They encourage young people to take their poems and make a digital story out of them. This is useful both because it gets them engaged with the artform, but poetry can serve as a helpful indicator of what is going on in the student’s head. They might not immediately be able to talk about issues they are experiencing in their personal lives, but you can start to identify it through the metaphors used. One of the aspects of this project I really liked was that they would never made the sessions a ‘safe space’. Eric said they never guarantee safety, as “safety is a fallacy”.

Over the last year, the project engaged eight school, and sometimes as many as three different classrooms within each. They usually aimed to do two sessions a week for five weeks. The project worked with young people ages 11-17, and the team adapted how they approached the delivery depending on their age. High schoolers were given a little more agency, while the younger age groups had more of a framework. In general, the team ensures that the students aren’t given too much independence. “Students work really well when you give them boundaries,” and giving them total freedom can be overwhelming.

On the whole, they found that the more time they had to spend with the pupils, the more successful the outcomes. Afterschool is not successful for arts engagement, it has to be delivered in a classroom and be apart of the curriculum.

The actual digital storytelling process starts offline. Students are asked to begin by planning out physical storyboards. They are then introduced to the different apps available, and are taught how to use them. Then, once they have a grasp of the apps, they are encouraged to choose an app that will be represent their story. It can be an animation or audio and accompanying imagery.

A key component about the digital storytelling initiative is redefining success. The project isn’t about having a completed video, but it’s about learning from the process, and feeling proud of the work they did produce.

This work is celebrated by a ceremony at the end of the workshops, where students and parents come together to see the finished pieces. Students are encouraged to introduce their video, but it can also be completely anonymous if they wish. There is even the option to not show their work at all if they don’t feel comfortable.

This project “is about the student’s voice”, so not being a native language speaker isn’t a barrier to access either. By allowing children the freedom to use whatever language is comfortable to them gives them the flexibility to create personalised pieces. The project is “allowing students to speak their truth,” and it might be the first time that teachers have heard students produce fluent coherent sentences, even if it is in their native tongue.

Given that the UK is currently prioritising STEM over STEAM, I asked what the reception had been in the US to this creative medium. It turns out that the focus on stem is actually serving as the entry point, as the dearth of creative elements in education has teachers crying out to introduce it and incorporate it into the curriculum. But also, at the same time the project is very much STEM as it is teaching essential tech literacy.

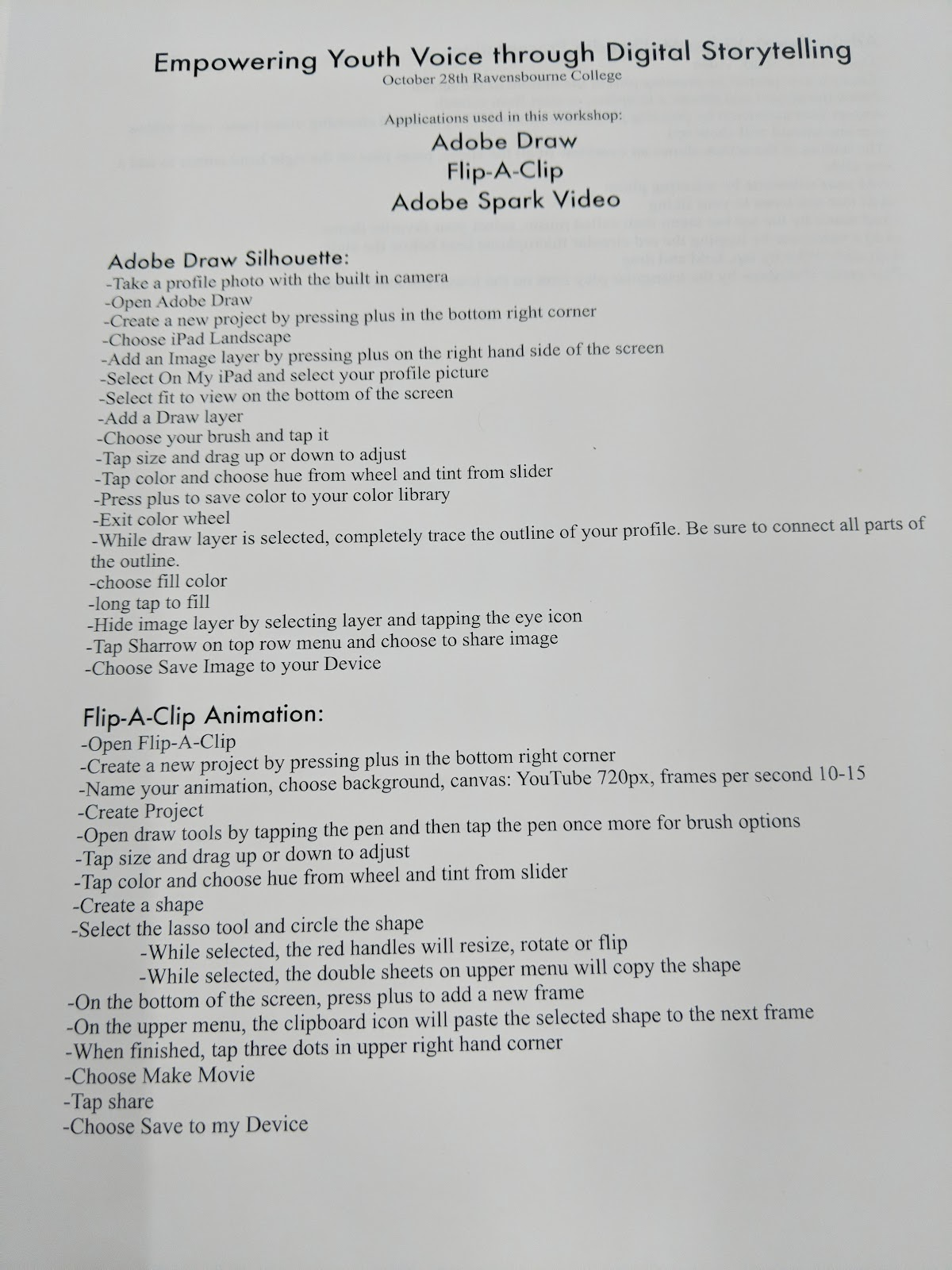

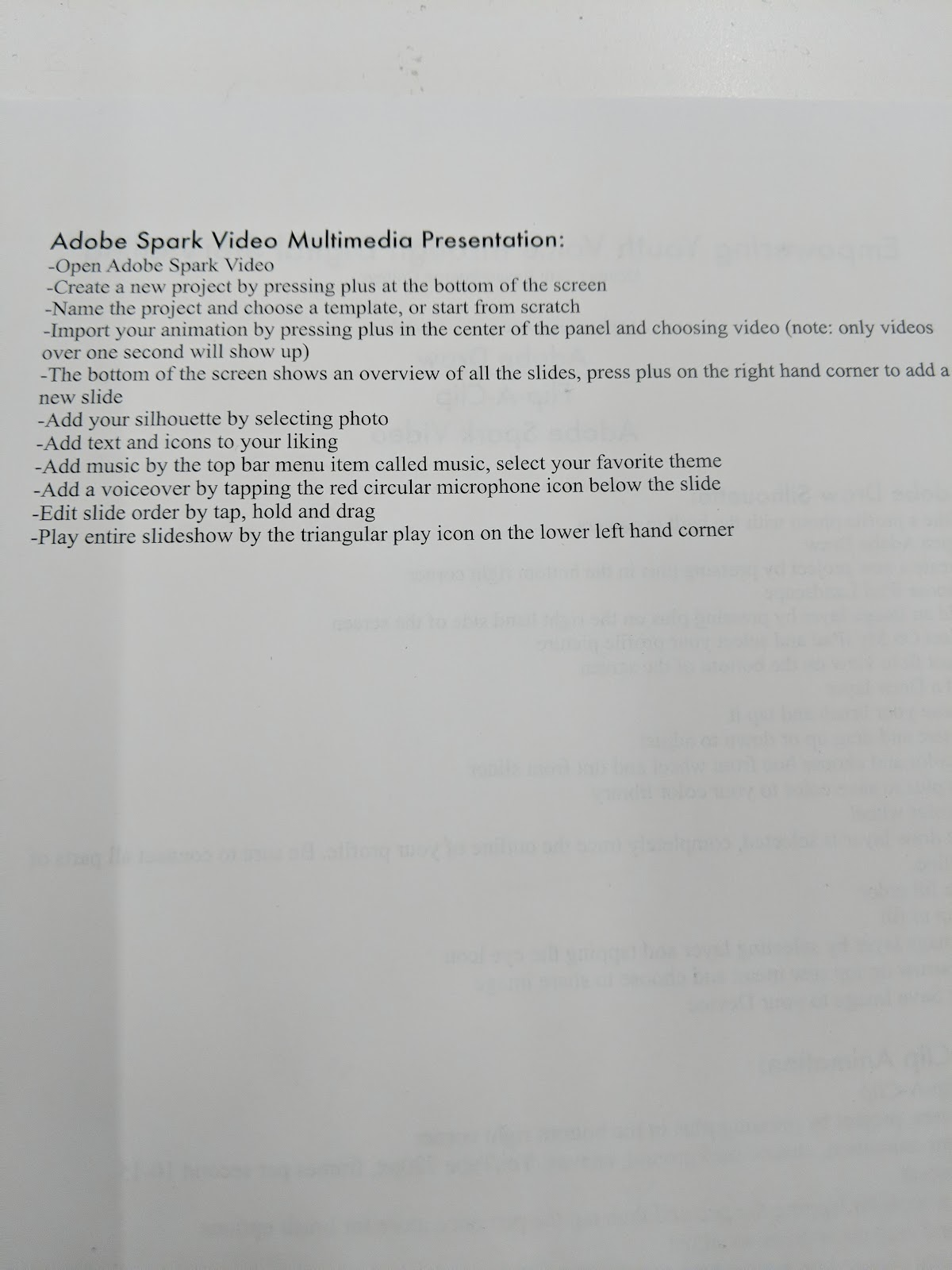

Olive and Eric were kind enough to hand out resources detailing the apps they use and some instructions on how to use them.

I have copied them for you to view.

0 Comments